As I mentioned the other day, every year, the Norwegian Refugee Council analyzes crises that have caused more than 200,000 people to be displaced from their homes, then publishes a list of the world’s ten most neglected crises. “The crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” they write, “has become a textbook example of neglect, featuring in this list six times in a row.” It has been at the very top of the list now for two years.

Again, the numbers, and the story of suffering they tell, are astonishing. Hunger in DR Congo has reached the highest level ever recorded, with 27 million people—a third of the country’s population—on the verge of famine or starving. More than 5.5 million Congolese have been internally displaced. Another million have sought refuge outside the country.

But no one—save those affected, obviously—has been paying much attention:

DR Congo was marked by fatigue in 2021. Not from the women, men and children who lived through the daily reality of insecurity and struggle, but from political leaders and the media who once again paid little attention to the crisis. There were no high-level political discussions concerning DR Congo, such as senior officials’ meetings, donor conferences or summits. The absence of strong international political engagement was matched by the lack of media coverage. Of all the 41 humanitarian crises analyzed by NRC, DR Congo received the lowest level of media attention when compared to the number of displaced people.

There is a UN peacekeeping mission to DR Congo, MONUSCO. Despite its efforts, the northeast of the country has been plagued by conflict. Recently, there has been a dramatic increase in attacks on displacement camps: Women, men, and children who had already fled their homes have been murdered in the places they had sought refuge.

The deadliest conflict since World War II

The day before yesterday, the King of Belgium arrived in Congo. He brings with him a tooth: the last remains of Patrice Lumumba, hero of the anti-colonial struggle and the first, short-lived, prime minister of independent Congo.

Like many people, what I know about Congo I know from reading King Leopold’s Ghost, by Adam Hochschild. I don’t know if the book is well-regarded by professional historians, but I found it a gripping and coruscating account of the rubber terror. Between 1885, when the Berlin Conference formally recognized the Congo Free State, and 1908, when it became a Belgian colony, the territory surrounding the Congo River was the private charnel house of King Leopold II of Belgium, to exploit as he pleased, in a brutal campaign of terror, massacres, and mutilation—the most murderous chapter in the European Scramble for Africa.

The lack of accurate records makes it difficult to quantify the number of deaths that ensued. Hochschild offers the figure of ten million, arguing that King Leopold was a monster on the order of Hitler and Stalin. Other historians have challenged this figure. But there is no doubt about the monstrosity. King Leopold’s private army, the Force Publique, terrorized the Congolese, who were forced to work under the threat of having their hands and feet cut off. Women were raped. Men were killed. Villages were burned. Administration officials demanded a severed human hand for every bullet issued. Slaves who failed to produce their quota of rubber were routinely mutilated or tortured to death— flayed by the chicotte, a whip made of dried hippopotamus hide. One administration official decorated his flower garden with a border of severed human heads.1 Leopold used the money to buy baubles for his teenage mistress.

In a 2002 article in the African Journal of Political Science, the political scientist Mwesiga Baregu wrote,

One of the most vexing questions regarding the current conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo is the question of periodization. This is mainly because the DRC has been through a series of continuous conflicts and wars ever since it became King Leopold’s personal colony in 1885. Indeed it can be persuasively argued that the Congo has known no peace since the onset of the slave trade in the 16th century.

The Second Congo War—also known as the Great War of Africa—is said to have begun in 1998. It was, arguably, a continuation of the First Congo War; it was inarguably the most deadly war the planet has seen since the Second World War. By 2008, 5.4 million had perished, chiefly through starvation and disease—although these figures, too, are contested. Civilians have been robbed, displaced from their homes and villages, and impressed into slavery. More than a million women and girls have been raped.

Although the war nominally came to a close in 2003 with the signing of a peace treaty and the transfer of power to a transitional government, hostilities and multiple insurgencies continued, to the point that some speak of a Third Congo War. In 2019, 4.8 million Congolese were displaced, more than at the height of the official war. The provinces of North and South Kivu are the center of the violence, with more than 130 armed groups now based in these provinces.

But what is the war about?

It’s extremely convoluted.

In the First Congo War, Laurent Désiré-Kabila overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko with Rwandan and Ugandan assistance. When Kabila then broke ties with Rwanda and Uganda, they retaliated by invading, initiating the Second Congo War. Within months, nine African countries were involved. Kabila was backed by Angolan, Namibian, and Zimbabwean troops. Rwanda and Uganda supported rebellions in the eastern and northern Congo.

As the designation “Great War of Africa” suggests, this was a transnational affair: Uganda, Rwanda, Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Chad, and Sudan were all drawn in. But the war was fought along ethnic lines, too, with violence between Hutus and Tutsis a significant driver of the conflict. A dense web of alliances emerged, with more than 25 armed groups fighting each other, constantly changing sides and killing their former allies.

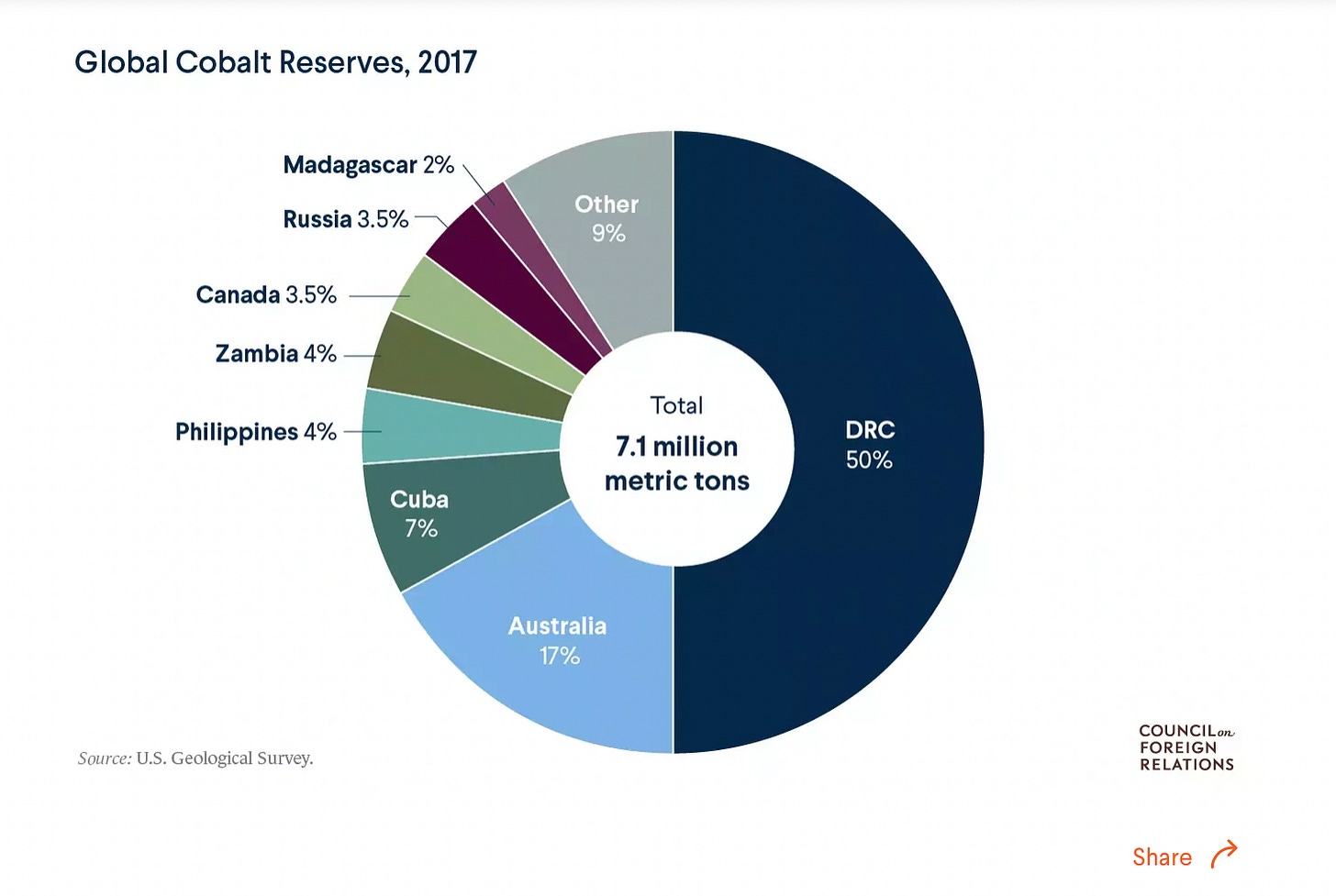

It’s tempting to view this conflict as so remote—and so rebarbative—as to be worth no investment of time in trying to understand it. But even if human suffering leaves you cold, the strategic significance of the region should get your attention. It can be summarized in one chart:

Why do we need cobalt? Because it’s the key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries. The laptop or phone you’ve got in your hands is running on it. You’ve got a part of this miserable conflict in your hands, in other words. A single electric car battery requires between five and fifteen kilograms of cobalt. Global demand for cobalt in the battery sector has tripled since 2011.

That’s not the only reason you need cobalt. It’s used in the superalloys that power gas turbine engines. No cobalt, no jet aircraft. It’s essential to terrestrial energy generation. It’s a catalyst for the petroleum and chemical industries. It’s the key ingredient in corrosion- and wear-resistant alloys, drying agents for paints, dyes and pigments, porcelain enamels, high-speed steels, magnetic recording media, magnets, and steel-belted radial tires. No cobalt, no modern world.

But wait, there’s more. The DRC is where you find all the minerals essential to the Fourth Industrial Revolution. High-grade lithium. Tin. Niobium. Tungsten. Coltan for mobile phones. Tantalum for the capacitors in every kind of electronic device. Every product you use—your hearing aid, your pacemaker, your MP3 player, the airbag in your car—runs on Congolese minerals. Google, Apple, Tesla, VW, BMW, BASF, and Glencore would be out of business tomorrow without them.

Without Congolese minerals, there’s no high-capacity connectivity, touch interfaces, virtual reality, robotics, 3D printing, Internet of Things, big data and cloud computing, or artificial intelligence systems. And there’s no renewable energy—solar, wind, wave, or hydroelectric.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo should be the wealthiest country in the world. Its untapped mineral deposits are estimated to be worth US$24 trillion. It has a mild climate, and rich, fertile soil. It’s blessed with abundant water from the Congo river, the world’s second largest. It has a sixth of the world’s hydroelectric potential. As Hochschild writes, the river’s “fan-shaped web of tributaries constitute more than seven thousand miles of interconnecting waterways, a built-in transportation grid rivaled by few places on earth.”

It should be a paradise.

But it isn’t.

Reading: The First, Second, and Third Congo Wars

For those of you in a hurry, here’s a brief, animated history:

Below are links to accounts of the conflict that look more reputable to me; although again, I’m not a scholar of this region or this period. If I’m mistaken to think these are serious accounts, I would welcome correction by people whose knowledge of the situation is deeper than mine.

A brief history of the Conflict, by the Eastern Congo Initiative:

The 1994 Rwandan genocide:

In the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide in which 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed, millions of Rwandan refugees flooded into the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

As a new Tutsi government was established in Rwanda after the genocide, more than two million Hutus sought refuge in eastern Congo.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that only 7 percent of these refugees were perpetrators of the genocide—often referred to as Interhamwe or FDLR (the Federation for the Liberation of Rwanda).

The First Congo War:

In 1996 Rwanda and Uganda invaded the eastern DRC in an effort to root out the remaining perpetrators of the genocide.

A coalition comprised of the Ugandan and Rwandan armies, along with Congolese opposition leader Laurent Désiré Kabila, eventually defeated dictator Mobutu Sese Seko.

Laurent Désiré Kabila became president in May 1997 and in 1998 he ordered Rwandan and Ugandan forces to leave the eastern DRC, fearing annexation of the mineral-rich territory by the two regional powers.

Kabila’s government received military support from Angola and Zimbabwe and other regional partners.

The Second Congo War:

The ensuing conflict has often been referred to as Africa’s World War with nine countries fighting each other on Congolese soil.

After a bodyguard shot and killed President Kabila in 2001, his son Joseph Kabila was appointed president at the age of 29.

The April 2002 Sun City Agreement, the ensuing July 2002 Pretoria Accord between Rwanda and Congo, as well as the Luanda Agreement between Uganda and Congo, put an official end to the war as the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo took power in July 2003.

In 2006 Joseph Kabila won the presidency in the DRC’s first democratic elections in 40 years.

Rwandan-Congolese Cooperation

In 2008 the DRC and Rwanda joined forces to root out the FDLR in South and North Kivu provinces.

In January 2009 the CNDP split and as part of a deal between Rwanda and the DRC, Kigali put CNDP leader Laurent Nkunda under house arrest.

The remaining CNDP splinter faction, led by Bosco Ntaganda, was supposed to integrate into the national army. But instead, Ntaganda led a new rebel group, M23, which became active in eastern Congo in 2012.

Ntaganda, also known as “the Terminator,” walked in to the US embassy in Kigali in March 2013 and surrendered to the International Criminal Court’s custody. Accused of thirteen counts of war crimes and five counts of crimes against humanity, Ntaganda’s trial is currently underway in The Hague.

Current conflicts in eastern Congo:

The peace process in eastern Congo continues to be fragile with multiple armed groups operating throughout the region, terrorizing civilians and blocking the path to long term peace.

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda: The FDLR currently operates in eastern Congo and Katanga province with an estimated 2,000 combatants. The FDLR’s official mission is to put military pressure on the Rwandan government to open an “inter-Rwandan dialogue.”

The Allied Democratic Forces: ADF is a Ugandan rebel group based along the Rwenzori Mountains of eastern Congo that currently numbers approximately 500 combatants. Most of its members are Islamists who want to establish Shari’a law in Uganda.

The Lord’s Resistance Army: LRA is a Ugandan rebel group currently based along the northern border areas of Congo as well as in the eastern Central African Republic. The group was formed by members of the Acholi tribe in Northern Uganda.

The National Liberation Forces: FNL is a Burundian rebel group originally formed in 1985 as the military wing of the Hutu-led rebel group, the PALIPEHUTU. The FNL currently appears to be in an alliance with Mai Mai Yakutumba and the FDLR in South Kivu.

Mai-Mai Militias: There are currently six Mai-Mai militias (community-based militia groups) operating in the Kivus: the Mai-Mai Yakutumba, Raia Mutomboki, Mai-Mai Nyakiliba, Mai-Mai Fujo, Mai-Mai Kirikicho, and Resistance Nationale Congolaise.

For two decades, the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo have been the epicenter of the deadliest conflict since World War II. Part of a vast country straddling the heart of Central Africa, the eastern Congo continues to defy efforts at pacification. As the conflict has morphed from a regional war to a series of tenacious local insurgencies, the civilians caught in the middle have paid the steepest price.

In addition to the ongoing humanitarian crisis, continued instability in sub-Saharan Africa’s largest country by area has strategic implications for the entire region. The DRC’s vast natural resources hold great potential but also complicate efforts at peace. The eastern Congo’s minerals power the world’s consumer electronics, and the country’s largely untapped farmlands have the potential to feed the rest of Africa. Yet disputes over these resources drive the conflict, and rebel groups seek to control them to fund their own campaigns.

The clones of “Mr. Kurtz”: violence, war, and plunder in the DRC:

This paper sets out to review the activities of the actors in the DRC placing special emphasis on their particular interests and how these interests have worked to promote or obstruct the peace efforts in the DRC. The main argument is that essentially their real and perceived interests drive the strategies and actions of the major actors in regional conflicts. The strategies and tactics adopted by the various actors before, during, and after the negotiation of various peace agreements have been largely shaped by the logic of these interests, albeit within the limitations imposed by the interests of other actors. Thus there are times when some actors have collaborated in pursuit of their mutual interests and other times when they have conflicted because either their interests clashed or they have failed to come to some mutually beneficial arrangements, which can accommodate their mutual interests.

Easing the turmoil in the eastern DR Congo and Great Lakes:

President Félix Tshisekedi may have opened Pandora’s box by inviting troops from neighboring countries to fight rebels based in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In November 2021, following deadly bombings in Uganda’s capital Kampala, Tshisekedi allowed Ugandan units to cross into the DRC’s North Kivu province in pursuit of the Allied Democratic Forces, a Ugandan rebel coalition whose largest faction has sworn allegiance to the Islamic State. The following month, Burundian soldiers reportedly marched into the DRC to battle the RED-Tabara rebel group. These interventions are causing fresh upheaval in a country that has suffered greatly from regional rivalries. Rwandan President Paul Kagame has warned that he might dispatch soldiers as well, while Kenya-led talks have revived a proposal for an East African intervention force. ….

The surprising re-emergence of the M23, a Congolese insurgency that had been dormant for almost a decade, is particular cause for concern, given its previous ties to both Kampala and Kigali.

Lessons from the UN missions to the DR Congo:

The UN mission in the Congo is perhaps best known for its military successes and failures. Scandals over inaction in the face of mass violence, and sexual abuse by uniformed personnel have made international headlines. On the other hand, robust peacekeeping operations have claimed successes and influenced UN-wide debates on the use of force.

The landscape of armed groups in the Eastern Congo:

Two years ago, Congolese armed forces celebrated a historic victory against the M23 rebellion, raising hopes that the cycle of violence in the eastern Congo was petering out. Today, however, disappointment has set in. At least seventy armed groups are active in the eastern Congo, and approximately 1.6 million people remain displaced. The various approaches taken by the Congolese government and its foreign partners—including the stabilization program, demobilization efforts, and security sector reform—have produced meager results. …

The East African Community’s challenges in eastern Congo:

While the EAC’s refusal to be passive in the face of eastern Congo’s toxic insecurity is commendable insofar as the prospects for regional prosperity would undoubtedly improve if the DRC were at peace, this latest development raises a number of questions. First, the EAC has set its sights on an extraordinarily difficult problem set, despite already having daunting security issues in its midst, not least South Sudan’s regular flirtations with complete collapse. The people of eastern Congo have suffered from violence and conflict since the mid-1990s with few respites, and over 100 different armed groups are thought to currently operate in the area.

The outbreak of the Ebola virus in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018, the tenth outbreak in the DRC, was the first time that the disease emerged in a conflict zone. This report, the second in a series on the Ebola epidemic, attempts to explain how the epidemic and the transnational effort launched to contain it (the Riposte) was affected by this violence, and how they in turn influenced the armed conflict.

🎧 I found this podcast especially helpful. Lawyer and human rights advocate Robert Amsterdam interviews Jason Stearns:

The Democratic Republic of Congo is one of the most resource-rich nations in the world, holding the largest deposits of critical minerals which will be key to the coming industrial transformation. But it is also a nation that is well into its third decade of war—a war that in many ways is forgotten, ignored, and buried away from public attention.

But one person who has been paying attention is Jason Stearns, a Senior Fellow at the Center on International Cooperation and Chair of the Advisory Board of Congo Research Group. In his exhaustively researched excellent new book, “The War that Doesn’t Say its Name: The Unending Conflict in the Congo,” Stearns explores how the conflict has continued despite the 2003 peace agreement, with the fighting becoming a structural economic activity.

In his discussion with Amsterdam, Stearns doesn’t hold back on the enabling role he has seen in the donor community, flooding the country with millions of dollars of aid while a narrow elite class has emerged among the military and security bureaucracy while the country has remained mired in war and poverty.

Stearns’ sharp and insightful on the crisis in the Congo is informed by more than a decade of experience working there on the ground in human rights organizations, leading him to present very compelling theories of how conflict has subsisted, why peacekeeping efforts have failed, and how we should start to think differently about intervention in Africa writ large.

Eastern Congo, Rwanda, and M23

Recently, signals have been coming across the transom of a new insurgency in eastern Congo. Here’s what the Congo Research Group said in April: A new insurgency? Navigating rumors and hype in the eastern Congo:

In the last several weeks, there has been a lot of noise about new insurgencies in the eastern Congo, possibly involving the Rwandan and Ugandan governments. This should provoke consternation: In the past, no local rebellion in the eastern Congo has been able to destabilize the region without outside support, usually involving those two countries.Since then, a number of NGOs have raised the alarm.

The Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect published this alert several days ago: Atrocity Alert No. 303: Democratic Republic of the Congo:

On 22 May heavy fighting erupted between Congolese security forces and rebels from the March 23 Movement (M23) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s eastern North Kivu province. In just one week the violence internally displaced at least 75,000 people and forced 11,000 to flee to neighboring Uganda.

The Center for Civilians in Conflict likewise published an alert.

As did the Norwegian Refugee Council.

Then I noticed this bulletin from the UN Security Council: Urgent action needed to defuse violence in Democratic Republic of Congo.

On May 22, M23 attacked UN Peacekeepers, I learned from a Security Council press statement.

Then on June 1, the Red Cross published an even more urgent alarm:

The intense, ongoing clashes in Rutshuru Territory between the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and M23 fighters have caused more than 72,000 people to flee their homes in the space of one week.

This struck me as important. A conflict that leads to the displacement of more than 70,000 people in a matter of weeks, an attack on UN peacekeepers, a UN Security Council call for urgent action—that counts as major news, doesn’t it? But apart from the bulletins above, all issued by NGOs, no one seemed to be noticing this.

I found one article, from Reuters:

Explainer: Why is there more fighting in eastern Congo?

Democratic Republic of Congo’s army has been engaged in heavy fighting since the weekend against the M23 rebel group, which is waging its most sustained offensive since a 2012-2013 insurrection that captured vast swathes of territory.

As you’ll recall, I asked on Twitter if anyone could help me better to understand what was happening:

Again, a number of people wrote to me, and again, it’s hard for me to figure out from here who has the most credible voice. But Honore Mvula Kabala, the National President of the political party Force des patriotes/DRC, sent me a compelling account of the problem, below. He wrote in French; the translation is mine. (If you’d prefer to read the original, send me a note.)

He stressed to me that international intervention would be helpful. Such intervention would perhaps come in the form of pressure on Rwanda, if Rwandan involvement is confirmed. Given Rwanda’s dependence on international donor aid, this could well be effective.

But the international community, he said, mesmerized by the unfolding catastrophe in Ukraine, is paying no attention to the crisis. He asked for my urgent help in publicizing the situation.

I told him I would do my best.

🚨 The war in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo:

What you need to know

By Honore Mvula Kabala

For more than 25 years, the Democratic Republic of Congo has suffered from wars and deadly violence in the east. Despite testimonies and reports of massacres, particularly during the wars of the 1990s, no protagonist has ever been tried. Will justice ever be served for the crimes committed in the Democratic Republic of Congo since the 1990s?

The entry of AFDL forces into Kinshasa was met with enthusiasm by the Congolese population, which mobilized around the UDPS and made the task easy for a movement that called for the liberation of the Congo against Mobutu’s dictatorship. But the population was quickly disillusioned when it began to face the abuses and murders that the Rwandan troops committed every night in Kinshasa: theft, rape, extortion of all kinds, illegal occupation of houses. Unease and fear soon set in. Thus Tshisekedi would demand of President L.D. Kabila the immediate return of Rwandans and Ugandans to their respective countries.

But the Rwandans had a completely different agenda; for them, it was—as foreseen in the Lemera agreements—to settle permanently and to exploit the wealth of our country in the territory granted to them under these agreements. In their view, this was the price for their assistance in helping Mzee Laurent-Désiré Kabila to take power.

And Paul Kagame often reminds anyone who will listen of this. To do this, they succeeded in convincing the Americans that the Congolese had no sense of responsibility or patriotism, and as a result, are unable to manage a very large territory—thus we must revise the borders that emerged after the Berlin Conference of 1885.

They said that they were better disposed, intellectually, to manage this country. They claimed that the Congolese Zairians had no sense of republican loyalty. “See how the general officers, whom Mobutu had fashioned, all betrayed him. They are good for nothing.” Even today, they said the same thing to the Americans after the assassination of President Kabila: Look how the Congolese lack loyalty.

So it’s no longer a secret to anyone: The war in the east is motivated by a hunger for economic gain and territory. Indeed, ever since the Lemera Accords granted part of our land to Rwanda, Paul Kagame has made this his hobbyhorse, because he doesn’t have enough room for his own population.

Moreover, small Rwanda is economically weak. It seeks to regain its economic and financial health by plundering our minerals, in complicity with Congolese traitors and certain Westerners. This is why we see mineral processing plants in Rwanda even though it has no mineral deposits of its own. This war would put little Rwanda on the map, economically. Already under a state of siege, Rwanda has had trouble in certain sectors of its economic and social life.

As far as war is concerned, Rwanda hasn’t got the military capacity for it—neither in men, nor in arms, still less in war tactics, because in the African power rankings, Rwanda is far lower. We need is to capitalize on our strengths to teach a lesson, once and for all, to this small country and its poor, arrogant leaders.

It should be remembered that Rwanda is animated by a superiority complex, having accomplices infiltrated in our FARDC (the armed forces) and security services. It maintains a derogatory complicity with certain dignitaries of our country. They believe they have control of our entire security situation. We insist that a systematic survey be done in the army and security service in order to remove these infiltrators, who constitute a real danger for the nation.

How should we understand that this multitude of senior officers have been unable to end the war for more than twenty years? What good are they if they’re so unproductive? They are paid more than they’re worth with Congolese taxpayers’ money. This is economic and security suicide. A purge in the army and our security services must be the priority if we want real peace in the East.

The expulsion of the Rwandan ambassador, who is a danger, and the recall of our ambassador is imperative. We don’t negotiate with a rogue state like Rwanda. We need acts of military deterrence. Force is the language we need.

Now you know as much as I do about the situation. In light of this, here are the only recent news items I could find. As with Ethiopia, the paucity of news coverage in comparison to the significance of the story is astonishing.

The King of Belgium is visiting DRC Congo right now, which has given rise to a spate of articles about Belgian colonialism, but these articles barely hint at the country’s present-day travails. Not one US news outlet, as far as I can see, has published an article about the circumstances Monsieur Kabala described above—although several European outlets have, and more have been published in the Francophone press. I did find a feature about a confused Congolese student who pitched up to fight in Luhansk.

The only way an ordinary person would know about recent developments in DRC Congo is by scouring the Internet for news about it—and even then, the only substantive reports you’ll find are from NGOs and the UN.

Belgian king returns mask to Congo in landmark visit:

The king of Belgium on Wednesday handed over a large wooden mask to the president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of thousands of objects taken long ago to the European country from its former colony. …

But for many Congolese, speaking out on social media, it was not nearly enough. They asked for an apology for the notorious crimes committed against their ancestors in order to enrich the king’s forebear, Leopold II, who claimed the territory as his personal fiefdom in 1885 and plundered it for more than two decades.

Belgian king expresses “deepest regrets” over DR Congo colonial past.

Belgian King regrets colonial “humiliation” in landmark Congo trip.

Congo’s Tshisekedi says “goal is to build something new” with Belgium. “The past is both glorious and sad, I would say. But the aim here is to build something new and, above all, something definitive that is constructive for both our countries.”

The Congolese student fighting with pro-Russia separatists in Ukraine:

[W]hen the head of the Kremlin-controlled, self-declared Luhansk People’s Republic announced a full military mobilization of the region on 19 February, Sangwa, together with two friends and fellow students from DRC and Central African Republic, decided to join the local militia and take up arms against Ukraine.

DR Congo’s President Tshisekedi accuses Kigali of backing M23 rebels:

President Felix Tshisekedi said Sunday there was “no doubt” that Rwanda was backing a rebellion on their territory, but insisted he was still seeking peaceful relations with Kigali. His remarks were just the latest exchange against the background of the resurgence of the M23 rebels active in the east of the country, near the border with Rwanda. …

DR Congo’s neighbors should not mistake its desire for peace with weakness, he added. “That does not constitute an opportunity for neighbors to come and provoke us,” he said.

Rwanda says territory shelled by Congo, requests probe:

Rwanda said on Monday that it had requested a regional body to investigate shelling of its territory by the military of neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo and that the attack had injured several people and damaged property. The alleged incident could further inflame relations between the two countries, which have long traded accusations about support for militant groups.

Mossad, a mining magnate and a mystery in Congo:

Dan Gertler, aged 48, the scion of a diamond-trading family, began doing business [in the DRC] in the 1990s and has since bought lucrative mining concessions, partly due to his closeness to Laurent and Joseph Kabila, father and son, who presided over the country, one after the other, from 1997 until three years ago. Mr Gertler’s interests in Congo have included diamond, copper and cobalt concessions, some of which he sold on to Glencore, one of the world’s biggest commodities traders.

Rwanda accused of sending troops in to Congo as border dispute grows:

The armed forces of Democratic Republic of Congo have accused Rwanda of sending 500 special forces in disguise into Congolese territory, the latest accusation in an escalating dispute between the neighbors.

Rwanda’s army spokesman said it was a fake story. A government spokeswoman said Rwanda would not respond to baseless accusations. In a statement, the Congolese military said 500 Rwandan special forces, wearing a green-black uniform that is different from their regular uniform, had been deployed in the Tshanzu area in North Kivu province, which borders Rwanda.

Rwanda says soldiers kidnapped by rebels in DR Congo:

Rwanda on Saturday said two of its soldiers were being held captive by rebels in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwandan government authorities of backing the group responsible. [sic] It comes after DRC summoned Rwanda’s ambassador and suspended flights from the country after accusing its neighbor of supporting the M23 rebel group active in its eastern region.

DRC Army: M23 rebels kill two Congo soldiers as fighting resumes:

The rebels shelled an army position in North Kivu, killing two soldiers and injuring five. Congo accuses the neighboring state of supporting the M23, which Rwanda denies. That clash followed a raid on a village in neighboring Ituri province on Sunday by suspected Islamists from another rebel group that killed at least 18 people, local sources said.

World Bank to fund development projects in eastern Congo:

The World Bank and Congo have signed two funding conventions worth US$900 million to boost female entrepreneurship and access to water and electricity in the east and west of the country.

Congolese refugees stream over Uganda’s border:

Since March, up to 500 refugees a day have been silently streaming into the east African country via Kisoro, a picturesque district in southwest Uganda dotted with endless hills, streams and a lake. Uganda is home to 1.5 million refugees, the most hosted by any African country.

Congo auditor says US$400 million missing:

More than US$400 million in tax advances and loans that Democratic Republic of Congo’s state mining company Gecamines said it paid to the national treasury cannot be found, according to a report by the government’s public finances watchdog.

DR Congo’s planned auction threatens carbon sinks, forest pact:

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s plan to auction oil exploration blocks next month threatens to disrupt some of the world’s most important carbon sinks and could jeopardise a US$500 million dollar forest preservation agreement.

At least 20 dead in new DR Congo massacre:

The attack took place overnight in the village of Bwanasura in Irumu territory, the Kivu Security Tracker (KST) said on Twitter. David Beiza, head of the Red Cross in Irumu, said volunteers from his organization “have counted 36 bodies” at the site of the massacre. (How this became “at least 20,” I don’t know—Claire.)

Ituri and neighboring North Kivu province are struggling with attacks by armed groups, many of them a legacy of wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s east. KST said the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF)—a group that the so-called Islamic State describes as its affiliate—was suspected to have been behind the killing.

Uganda and Congo extend joint military operation in east Congo:

Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo on Wednesday extended a joint military operation launched late last year against Islamist insurgents in east Congo, the operation’s spokesperson said. Uganda sent at least 1,700 troops to its central African neighbor in December to help fight a violent rebel group known as the Allied Democratic Forces—the largest foreign intervention in Congo in over a decade aside from a United Nations peacekeeping operation.

I couldn’t find a single article in English written by a reporter who lives in the DRC. All of these articles seemed to be based on reports from the Red Cross, the UN, or other NGOs.

But it’s an awfully big story, isn’t it?

Next, we’ll look at Mali.

If you haven’t read the book but want to understand the historiography, this is a good review.

I have been peripherally aware of the situation in Africa for some time, and greatly appreciate the detail you provide.

However, it's one thing to know about a problem, but what can be done about it? Sending "lawyers, guns and money" doesn't seem useful. Sending food might be, but that might only empower those already with the guns and money.

I suspect that many people turn away from paying attention to Africa because they do not see what can be done to improve the situation.

Thank you, Globalists, for providing these insights into overlooked crises. We Americans need to start paying more attention to what goes on around the world.