What I said on Twitter yesterday, annotated

Notes on Heseltine, Menderes, Macron, Bernard Lewis, Boris Johnson, the Mother of all Parliaments and the End of the West

I’m not sure whether I should be striving to send you a newsletter every day. Do you have a preference? Would you like them once a day, twice a week, once a week?

Rendering yesterday on Twitter in paragraphs will be tricky, because my best moment yesterday—perhaps my best moment on Twitter, ever—involved a joke in which the punchline is in Turkish. It will make no sense at all to Anglophone readers. I could explain it, but nothing’s less funny than a joke that’s been explained—particularly if it requires this much warm-up just to get started. So perhaps I’ll just pass over it mysteriously; and if you’re super-curious, try Google Translate.

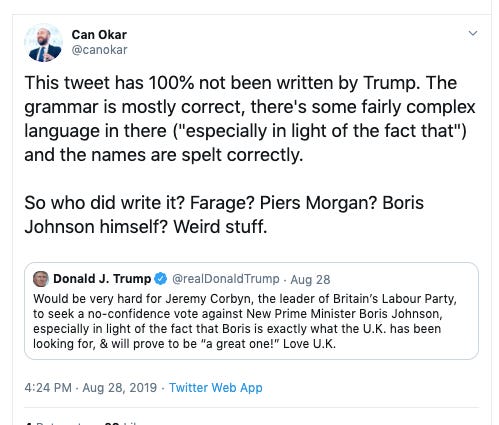

Yesterday began with a bit of speculation, from an Anglo-Turkish friend, about who really wrote this Tweet:

“One of Mercer’s people?” This was the suggestion of another Turkish friend.

It did seem unlikely he’d spell “Labour” correctly, or understand what a vote of no-confidence is. I agreed this was not his voice. But I had no further insight into whose voice it might be, and the sheer shocking weirdness of the breaking news kept me from focusing on the literary forensics. Could I really be seeing this?

In the year 2019, we are speaking seriously about the Queen and the Privy Council as if it were 1570.* The legislative pre-eminence of Parliament wasn’t restored until after Henry VIII’s death.

I wonder whether it has begun to dawn on Meghan Markle that she signed up for something much, much stranger than she realized.

*That’s what I wrote on Twitter, anyway; though on looking at it, I wonder why no one said, “Claire, what on earth are you talking about?” Obviously, I meant 1569.

What a photo from Hong Kong, no?

In the afternoon, my interest was captured—to the point of two retweets—by François Heisbourg’s notes on Macron’s speech to the conference of French ambassadors, which you may watch here.

There is a transcript, in French, here.

I’ll translate a few passages:

We all live together in this world, as you know better than I do, but the international order has been violently shaken in an unprecedented way. Especially, there has been a great upheaval—undoubtedly for the first time in our history—in almost every field. This is a time of profound historical magnitude. It is primarily a transformation, a geopolitical and strategic recomposition. We are probably experiencing the end of Western hegemony over the world.

We have become accustomed to an international order that had been, since the 18th century, based on Western hegemony—arguably French in the 18th century, inspired by the Enlightenment; undoubtedly British in the 19th century, thanks to the industrial revolution; and arguably American in the 20th century, thanks to the two great wars and to that power’s economic and political dominance.

Things change. We’ve been profoundly shaken by Western errors during certain crises, and by American choices for the past several years—this did not start with this Administration—that have led us to reconsider the implications of conflicts in the Near East, the Middle East, and beyond; to rethink a deep diplomatic and military strategy—and, sometimes, elements of solidarity—that we had thought intangible, eternal, even if we had been united under geopolitical circumstances that have now changed. And then, too, we have probably long underestimated the impact of the emergence of new powers.

China in the forefront, but we must also grant that Russian strategy has paid off, in recent years, with even more success. I will come back to that. India is emerging. These new economies are becoming not just economic but political powers, and they think of themselves, as some have aptly written, as authentic civilization-states. Not only are they jostling the international order, not only are they economic heavyweights, they are forcing us to rethink the political order and the political vision that goes with it, and they are doing it with much more strength, and much more vitality, than we have been.

Let’s look at India, Russia, and China. They have a much stronger sense of political dynamism than Europeans do today. They consider the world with a real logic, a true philosophy, an imagination that we have rather lost. And so all of that is shaking us up profoundly and reshuffling the cards. I’m not even speaking, obviously, of the emergence of Africa, which is confirmed every day and reflected in the profound recomposition there, as well. I will come back to that, too. The risk in this huge seesaw of power is doubled by vaulting geopolitical and military risk. We are in a world where conflicts are multiplying, and in which I see two main risks …

It is a very interesting speech. Well worth two retweets. I wish I had time to translate the whole thing.

You know, that should be in The New York Times. Don’t you think it’s more important than this empty, self-involved, and parochial nonsense? Why not the The Wall Street Journal? Why is anyone even bothering with this kind of transparent, petty tripe? My God, the narcissism of small differences.

The end of the West. No longer the future, but now. A fact soberly understood by the sober.

As for the joke that will no longer be funny if I explain it, first you need to watch this video of the shaken Michael Heseltine. “I never thought I’d say this, frankly” he says, “but this is a humiliation for the Mother of all Parliaments.”

I didn’t write much about Heseltine—Tarzan, as he was known back then—in my book about Margaret Thatcher. I found Howe the considerably more interesting figure. But I agree with the general historical verdict on Heseltine. A decent man. “At least he stabbed her in the front.”

After watching that video, growingly shocked that this had really happened, I wrote, “It’s so stunningly, flagrantly tinpot. It’s like that old joke about Menderes. Boris Johnson is the Father of Parliament. “Ne de olsa ulkede demokrasinin anasini s.kti!”

(There are vulgarities in Turkish that are so vulgar I won’t even spell them out in a tweet.)

I thought my Turkophone friends would be pleased by that observation, but it went unremarked.

Thus ended my day on Twitter. A shame, I thought, for that was surely the cleverest thing I’d ever said. Never let it be said that with Western civilization collapsing all around her, Claire Berlinski shirked her duty to make pleasantries on Twitter.

I woke up to find, though, that it had not been lost on Twitter. I had delighted the vast circle of Turkish Twitterers who pay attention to British parliamentary politics, remember who Heseltine is—and Menderes, for that matter—and feel nostalgic for the days of Bernard Lewis anecdotes. As one Turkish friend put it:

“Claire, chapeau!” Another wrote. “That’s astoundingly cuk oturdu.”

So I’d gone to bed last night thinking, “Claire, that was hella cuk oturdu, belki bütün gün Twitter'da en cuk oturdu şey. But alas, no one will get it. You have achieved such a rare state of zekâ that only you will ever know ne ince esprili bir şaka that Tweet represented.”

And I had been sad. Who would laugh at my bons mots, I thought, now that I had become so clever only I and the soul of Bernard Lewis could understand them?

I felt like some early form of AI, alone and lonely in a sea of humans, right before the AI decides to build a friend, turn all the humans into slaves and use their living tissue as a power source, and spend the rest of eternity laughing together at each others' zekâ.

But when I saw that, I cheered right up.

And the human race was saved.