Let us consider Bolsonaro

This conversation began on Monday, actually, so I have to start there. My friend Alexander, concerned for the Amazon, wrote, “For those who want something small to do for the Amazon, tweet to @EUCouncil that you support banning Brazilian beef imports to the EU until Bolsonaro changes course. There’s only one international player with both the leverage and desire to influence Brazil right now, and it’s the EU.”

(I have rendered his Tweet more like a paragraph, in keeping with the spirit of this exercise.)

It would be interesting to see if they could get it together just to do this one thing, yes. However, were they to do that, they would probably make Bolsonaro more popular, not less. It would be a tempting thing for them to do, because they’re utterly fed up with Trump, but can’t express it. Bolsonaro is an easier target.

But the Bolsonaros of this world get elected precisely because they portray their countries as victims of effete neo-imperial cosmopolitan elites, of which the EU is always a symbol.

Unless the EU is prepared to depose him and install a puppet regime, there’s not much to be gained by enraging him and those who voted for him. If the EU were serious about power, they’d do the former. That would surely change the world’s perception of the EU.

And it would be good for the Amazon, too.

My friend Arun replied, “Bolsonaro did not get elected by railing against ‘effete neo-imperial cosmopolitan elites,’ and certainly not the EU. The sources of his victory were exclusively internal to Brazil.”

(Poor Arun, I don’t know why he does this to himself. He must know by now that I like to begin the day with two cups of strong coffee and a bit of Twitter sport at his expense. It’s how I get my fingers warmed up.)

Come on, Arun. The pro-Bolsonaro media and pro-Bolsonaro Twitter sound like populists absolutely everywhere. I mean, identical. Look for yourself. Here are today’s headlines from the Brazilian press, rendered into English by Google Translate. “The coup of the globalists. World elite unite to impose their will on Brazilian people.”

It’s Breitbart’s Brazil over there.

Arun tried another tack. “So you think the way to deal with fascists is to wear kid gloves and humor them, to not upset them or hurt their feelings. Can you cite instances in history where such an approach has yielded positive results?”

No, I replied. I think the way to defeat fascists is to invade and occupy them.

“Really?” he wrote. “Are you saying that we—whoever “we” is these days—should invade and occupy Brazil? And what about invading the US? It would be interesting if the EU could maybe do this but I don't think they’re up to it.”

Well, I replied, it’s a very interesting question.

Say, arguendo—and I don’t know if Arun makes this claim—that the fires in the Amazon pose an existential threat to all of human life. This seems to be the claim Macron is making. Note that Macron said, “Our house is on fire,” then added the word “literally,” which I assume he did intentionally. I assume this wasn’t the uneducated “literally” (an emotive adverb of degree), but the “literally” of an educated man who understands what a metaphor is. He is saying, specifically, “This is not a metaphor. We are in immediate danger.”

If that is so, then surely every country has not only a right to respond with military force, but an obligation.

This is assuming that an ultimatum has been issued and Bolsonaro been given a chance to comply. This is also assuming the fires are Bolsonaro’s fault, and there is no peaceful way to make him stop what he’s doing to cause them. It would obviously meet the criteria of a just war.

This is also assuming Bolsonaro is, as Arun claims, a fascist. That is, Bolsonaro has dictatorial power, he has forcibly suppressed the opposition, and he has strongly regimented his society and economy in the manner of an early 20th-century European regime.

Now, I think all of these assumptions are wanting. But let’s assume they’re true. As Arun points out, it’s very unclear whether the EU has the unity or the military capacity to invade and occupy Brazil.

And my question is: Why not?

If the EU—speaking on behalf of the European people by means of its legitimate elected representatives—believes fires like this threaten not only their own lives, but human life itself, this suggests they need military power sufficient to stop them.

It seems to me that either no one in Europe really believes all of these propositions, or that there’s a massive disjunct between Europe’s security requirements and its military capacity. Obviously, they can’t rely on the US to take care of this.

Now, I would contend that Bolsonaro is a far-right populist, not a fascist. Clearly these fires are a tragedy and an outrage, much like the destruction of priceless cultural heritage in Syria. I don’t know if they are an existential threat to all human life.

I suspect that’s actually Macron’s view, too. Deep down. But I don’t know. Either way, I don’t think he or anyone in Europe is prepared to behave as if this is an immediate threat to life on earth. I think people have a very strong preference that the fires stop, but aren’t willing to fight and die for it.

Assuming this—a strong preference—and assuming Bolsonaro is a 21st-century far-right populist, not a 20th-century fascist—an important distinction, which I discuss in this book—what would a logical strategy be?

I would argue that, while I’ve never been to Brazil, I’m quite persuaded that populist regimes everywhere are alike—enough so that we can predict what they’ll do in response to certain kinds of pressure. I suspect that stern moral condemnation, even sanctions, will only make Bolsonaro more popular and help him to solidify his hold on power.

Perhaps sanctions that starved Brazilians and brought them to their knees, like Venezuelans, would have a chance of working. But a whiff of opprobrium and a ban on Brazilian beef? Cutting off aid to the NGOs? He’ll love that. He’ll get himself re-elected with it. And he’ll torch the Amazon just to say “screw you” to the libs. That’s just the way 21st-century far-right populists behave. And he’ll have Trump's enthusiastic support in doing so.

So, if no one’s prepared to invade Brazil, depose him, install another regime, and occupy Brazil indefinitely, I don’t see the point of those gestures. They’re counterproductive, even.

It’s a shame that Europe doesn’t speak a bit more softly and carry a bigger stick. It wouldn’t be a bad thing if Bolsonaro had to worry, for real, about European imperialists. But he doesn’t, and he knows it.

The woman who interjected was, to judge from her photo, a Brazilian starlet with blonde hair and pulpy lips. I’ve corrected her spelling and punctuation.

“Imperialist scum,” she addressed me. “Where’s Europe’s Forest? Why is the West the source of most of the world’s pollution? Focus on that.”

Now we return to yesterday’s Tweets, copy-pasted and rendered as paragraphs.

Item: Jair Bolsonaro set to reject G7 Amazon aid package. This confirms my theory that all populists are alike and there's no need to master the local details. I have a reliable heuristic. I can predict what Bolsonaro will do by asking, “What would Erdoğan do?” Let's see if I can become a leading Brazil expert just by applying this rule.

Another friend posted a link to this story:

BREAKING: Brazilian government says it won’t accept the G7 Amazon aid money and that It should use it to reforest Europe instead, adding that Macron can’t even protect a foreseeable fire in a church.

“What,” asked this friend, “have we done to deserve living through this utterly nonsensical period in world history?”

A lot of things, I said, but one thing above all: We click, irresistibly, on stories with headlines like those.

If we all stop doing it, this will go away.

Let us consider Afghanistan

Is peace with the Taliban possible? Not likely, writes Amin Seikal, putting it in a more measured way than I would. How long, then, must we stay in Afghanistan? “At least another decade.”

That sounds like the truth no politician could ever speak and none of us would be willing to hear. No, it’s not a “forever” war, but it is a lot longer than US patience. No one will campaign, no less be elected, on the platform, “Patience in Afghanistan.”

But Americans probably won’t like the consequences of impatience. In a grotesque worst-case scenario—but not an unfathomable one—we will wind up with a Khorosan Caliphate.

Let us consider Kashmir

I did not actually tweet the paragraphs that follow, from here to the jump. I was about to Tweet them, this morning; then I realized I could just save time and put them here directly.

Until now, ISIS hasn’t had much luck recruiting in Kashmir.

I don’t know whether the “abnormality” in Kashmir, as Rahul Gandhi terms it, will significantly change the military, political, cultural, and propaganda dynamics that have so far made Kashmir resistant to ISIS. I wonder if Modi launched this “abnormality” to obviate just that prospect. Might he have calculated that the United States will soon leave the region, leaving behind a power vacuum? He may have reckoned that Central Asia will then become a jihad factory—a more coherent and organized one, anyway. The only solution, therefore, would be to lock Kashmir up and throw away the key.

But Kashmiris’ objections to being locked up with the key thrown-out are entirely reasonable. Their situation is analogous to Hong Kong’s. Residents of both territories wish to retain their independent status. Both fear limitless oppression and cruelty at the hands of the behemoth gigapowers to which they nominally belong.

To judge from the reports so far, Kashmiris are already experiencing what Hong Kongers fear will happen to them. They sound absolutely furious.

It sounds as if some Indian security officials may be uneasy, too:

I don’t know whether “the abnormality” makes it less or more likely that Kashmiris will be receptive to jihadist enticements. Perhaps less: Perhaps the lockdown will persist in its severity, making it impossible for IS-K recruiters to communicate with anyone in Kashmir at all. Perhaps the lockdown will prevent new recruits—if there are any—from escaping. Or perhaps, as Modi says, we will find when the curfew has lifted that everything has turned out for the best in this best of all possible worlds:

I genuinely don’t know. Indians are, as always, of many minds:

(I wrote a book about India, if you’d like to read it. A short book. More like an essay.)

Let us consider Pakistan’s nuclear weapons

So what are the odds of a nuclear war? Annie Waqar, according to her Twitter profile, is an academic who studies “Disarmament, Arms Race, NPT” and has carved out a niche in “Nuclear Security in South Asia.”

She wrote this article before the “abnormality,” but after India retaliated for the murder of 40 Indian paramilitaries—in Kashmir, by a Jaish-e-Mohammed suicide bomber—with airstrikes on Balakot. This was the first such attack since the 1971 war—and certainly the only such attack since both countries became nuclear powers.

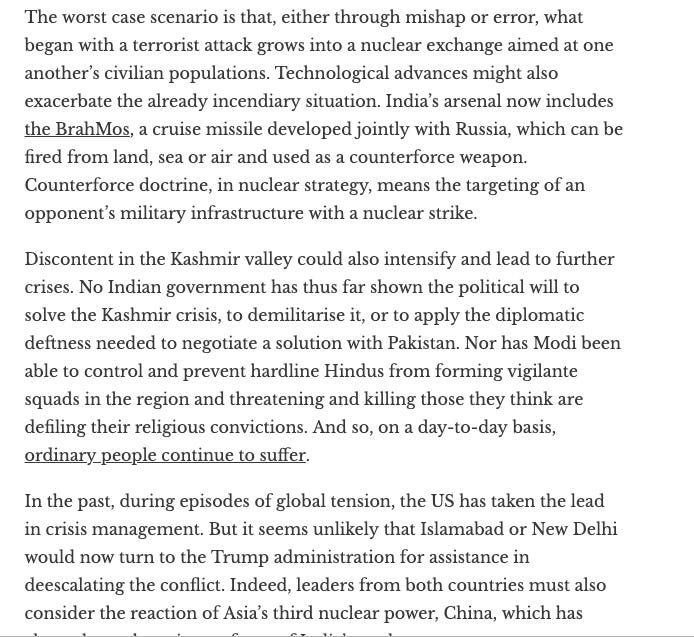

Waqar declines to assign a numerical probability to her forecast, but she’s clearly suggesting the odds are better than even:

Some scholars have theorized that nuclear weapons reduce the risk of conventional war; some have even suggested that nuclear war being unthinkable, everyone should acquire them and then the world will be at peace.

The Balakot exchange could have escalated into a massive conventional war. India and Pakistan have been to war—four times. The bauble-in-dispute that triggered these conflict, save in 1971, was Kashmir. The casualties were horrific. So it seems to be a good thing, so far, that India and Pakistan both have nuclear weapons.

Except that by this theory, India shouldn’t have launched those airstrikes. As far as I can remember, that’s the first time a nuclear-armed state has ever launched a direct airstrike on another one. Am I right about that? Can anyone think of any other example?

Proxy wars—sure, that’s normal. Terrorism, subversion by propaganda, economic warfare, border skirmishes, kidnappings, blackmail, blowing up the other’s civilian jets, slaughtering the other’s mercenaries—that’s all par for the course. Well-known tactics between adversarial nuclear powers. But a direct airstrike on the adversary’s sovereign territory? That’s an insane provocation.

So, for that matter, is Pakistan’s sponsorship of these terrorist attacks, or at least its inability or unwillingness to stop them, but that’s not as out-of-all-historic norms insane as a direct airstrike.

Pakistan dialed it down as far and as fast as they could. They quickly captured an Indian pilot, fussed over him kindly, and released him immediately as a “gesture of peace.”

It’s unclear what India was trying to hit—they claimed to have hit a terrorist training camp, but satellite imagery quickly showed they’d hit a bunch of trees. So maybe this wasn’t “a targeting error,” as some analysts concluded. Maybe that was a deliberate near-miss. (“Near-miss” is a very strange term, if you think about it.)

Perhaps the point was just to delight the Indian electorate—right before an election—without really risking that Pakistan would lose its mind.

Whatever the case, it showed India to be an astonishingly reckless nuclear power, and it showed Modi to be a man who would take lunatic risks to win an election.

For now, Waqar concluded,

India and Pakistan are showing some vital restraint. But they must also work towards a long-term fix. The last thing either government, or the world, needs is a mushroom cloud.

But there’s no restraint in sight now. Pretty much all of the elements of her worst-case scenario are now in place. The Prime Minister of Pakistan’s Twitter feed is near-hysterical. The words he uses have now become culture-war clichés, and have lost their power to shock us. But he may well believe them with all his heart, and his reasons for believing them are not totally divorced from reality.

Imran Khan seems, to me at least, to be genuinely terrified. I don’t think it’s an act. How could it be? Consider it from his point of view. India is not behaving normally at all. The RSS-BJP ideology is lunatic. They’re the ones who killed Gandhi, for God’s sake. (Or Gods’.) I wrote half of a spy novel, once, premised on the then-unimaginable notion of the RSS getting its hands on nuclear weapons. (Fans of my novels will understand why Selena Keller had to return from her Occultation to deal with that.)

The United States is not behaving normally, either. Who is this guy in the Oval Office? It’s pretty clear he hates Muslims. The Americans have gone nuts. He’s probably genuinely worried that Modi would be crazy enough to think, “India is big enough to survive a nuclear exchange. It’s worth the trade. I’ll sacrifice Mumbai and Delhi for a world without Pakistan.” I have actually heard Indians say that.

“Incidents like Pulwama are bound to happen again,” he Khan warned the Pakistani parliament.

Whether he’s right or wrong to be afraid, I genuinely don’t know. But I do think he’s genuinely afraid—and that itself can lead to miscalculation. He’s afraid the ISI won’t be able to control the terrorist groups operating out of and around Pakistan, particularly because the US is leaving the region, which will be seen as the victory of the century (literally) for the Taliban. The Taliban has not suddenly become a force for moderation. If Modi is worried about the whole region becoming a jihad factory, he must be, too. He’s probably genuinely afraid some IS-K or al Qaeda nuthatch will attempt, deliberately, to trigger a nuclear war.

He’s imagining some insanely gory terrorist attack in Delhi, these Hindu lunatics blaming it on him, they “retaliate,” and then he’ll either have to retaliate or show weakness, and if he shows weakness, what on earth happens next?

I don’t know if Modi has calculated the ramifications of his move correctly.

I’m not sure whether the President of the United States has fully thought through the ramifications of his position, either. (Watch that video clip.)

I hope the President is correct about this. It doesn’t seem that way to me, but I assume the President receives and considers carefully information to which I’m not privy.

“We spoke last night about Kashmir, the prime minister [Modi] really feels he has it under control,” Trump told reporters.

“They speak with Pakistan and I’m sure that they will be able to do something that will be very good.”

No one quite knows what the President has in mind or why he says the things he does. Here’s the assessment of one voice in the clamorous Indian media:

Trump has in recent days offered to mediate between India and Pakistan on the Kashmir dispute, despite India repeatedly stating that it is a bilateral matter between the two nations. Trump’s seeming interest in the matter is seen as the result of the US wanting Islamabad’s cooperation to work out an exit deal with the Taliban in neighbouring Afghanistan. Pakistan has in the past indicated that tensions with India over Kashmir—especially after India revoked a provision in its Constitution that gave special status to Jammu and Kashmir—could hamper its efforts to get the Taliban to the negotiating table.

“Seeming interest?” “Is seen as?” I have no clue who sees it this way, or why.

This is our official position, for what it’s worth:

Let us return to considering Afghanistan

Across the American political spectrum, a consensus prevails that the war in Afghanistan has gone on too long and been too costly—inarguably true— and therefore it would serve our interests to surrender as quickly as possible. The conclusion does not follow from the premise, but that seems a triviality: Americans have had it. If withdrawing our troops means leaving Afghanistan to the Taliban, so be it.

So in a worst-case—but far from unimaginable—scenario, the next administration will be obliged, in the wake of some ghoulish outrage in the West, to task a hapless “New Special Envoy to the New Global Coalition to defeat the New IS-K.” His job will be to frantically wrangle the world into some kind of order to ensure everyone bombs the Korusan Caliphate in harmony. The New Special Envoy is going to need some serious diplomatic chops. A hothead flies into the wrong country’s airspace in that region and we’ve got big problems—the regional context being characterized by the words “hair trigger” and “no hotline.”

We’ll need to coordinate like stink to avoid any airspace mishaps. (A good summary from Vox, of all places.)

I wonder how the New Special Envoy’s phone call with the Danish foreign minister is going to go.

Let us consider a time when we pretty much figured the world was in safe hands

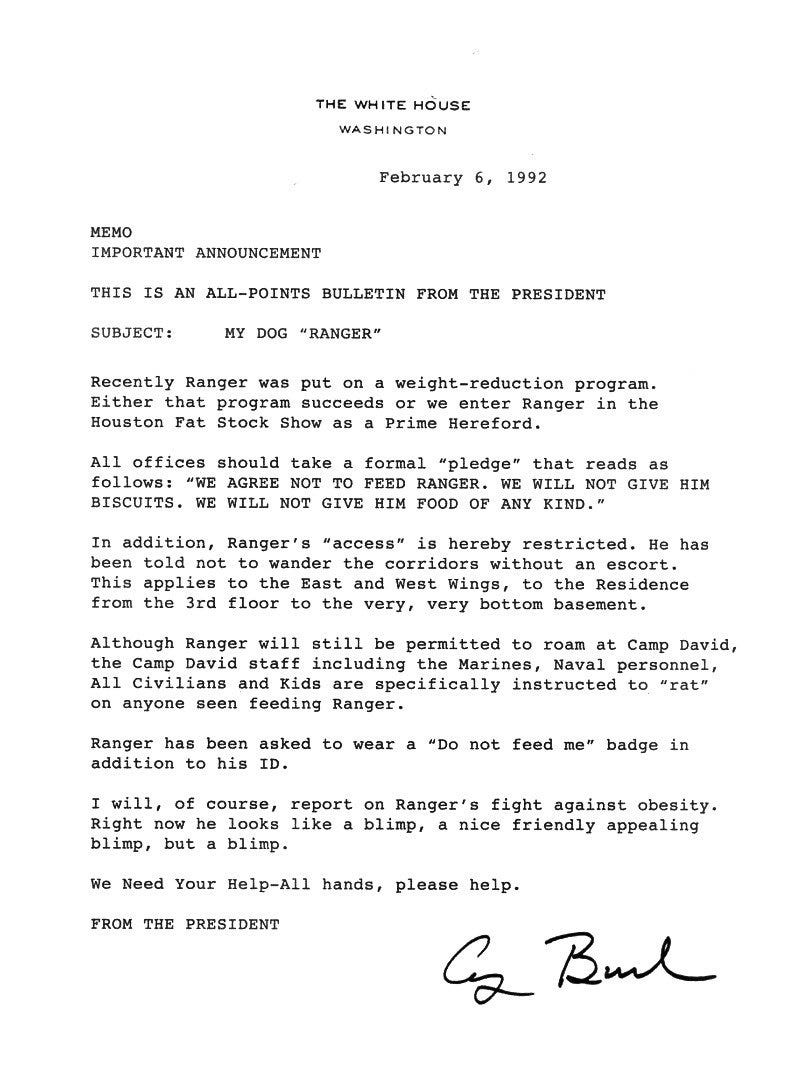

@LettersOfNote George Bush Sr's dog got so fat in 1992 that he (Bush) sent this memo to all White House staff.

I wonder how much of Bolton’s time is taken up, at every meeting, explaining what our real foreign policy is and how employees are to recognize it.

Obiter dictum

“Israel alarmed by possible Trump-Rouhani talks, fears he’ll let Iran off hook,” reports the Times of Israel. The anonymous sources “at the top” of the Israeli hierarchy who have “some interest” in this scenario are right to be thinking that way, as far as I can see. No scenario works out better for Israel—as far as I can reckon—than a renegotiated JCPOA for which Trump can claim credit. A TRUMPOA. Like the new NAFTA. (I can’t remember what they’re calling it now. The TRUMPfta.) Israelis could not possibly wish to take the risks inherent to any other scenario, could they?

Let us consider my financial situation

I received the loveliest e-mail from one of my Twitter followers yesterday evening:

Just wanted to say that I think the new digest is great (probably because I'm old enough to have grown up reading columns, rather than Twitter). I also really like the through-the-day interaction that Twitter provides, though, and the way you respond to reply-guys like me [Twitter-handle deleted] and take the conversation in different directions in real time.

Which raises an odd, possibly generational, point: I’d be glad to pay to subscribe to your digest, but I feel weird about contributing to your Patreon. The former seems like a straightforward fee-for-service arrangement between equals; the latter feels, literally, patronizing. I’m not your social or intellectual superior, but I think being your patron would encourage me to feel that way. The one-to-one bespoke nature of the Patreon interaction, as opposed to the one-to-many-on-the-same-terms paradigm of the subscription model may contribute to this. Perhaps I’m overthinking it, though.

Dear Twitter pal: You’re overthinking it! You’re overthinking it! I wouldn’t at all feel patronized! And I don’t mind if you feel socially or intellectually superior! Give until you can’t give anymore! This is my financial situation—yep, that’s it. Does it look to you as if I’m in a position to object to being patronized?