The Years of Living Hysterically, Part II

Reflections on Joe Biden, Tara Reade, #MeToo, and our Hysterical Culture

TRITE LEARNING

Let’s return to the next part of Heckman’s defense, which is stranger still: “Plaintiff did not intend his remark to be a sexual comment about the Duchess. A reasonable person would not have construed his remark to be a sexual comment about the Duchess.”

Why would this need to be said? This was a photograph, not a Duchess, and what earthly concern would it be of a woman sitting twenty feet away from him even if it had been a sexual comment about the Duchess? Why was she eavesdropping on a conversation obviously not intended for her ears? Why should there be a taboo or a prohibition at all against a man making a “sexual comment” about a photograph?

Even had he said—quietly, to his male colleague—“Man, would I like to bang that Duchess,” it could in no way be construed by Corinne Segal as a sexual advance toward her, a request for a sexual favor from her, or verbal conduct of a sexual nature that explicitly or implicitly interfered with her work performance. Only if we accept that any comment of a sexual nature is of necessity “intimidating, hostile, and offensive” to women—even if they have to eavesdrop on a private conversation to hear it—could this make sense.

But that’s insane. To suggest it is to concede from the outset to lunacy.

In another concession to lunacy, the complaint continues, “By this remark, Plaintiff intended to convey that the Duchess possessed charm and beauty and was a suitable match for her fiancé, who has a reputation of possessing charm and handsome looks. Plaintiff did not intend his remark to be a sexual comment about the Duchess.”

What is this gobbledygook? What are we to conclude from this passage, but that Heckman agrees it would be a terrible thing for a man to make a comment of a sexual nature about a photograph of the Duchess of Sussex? That it is admissible to convey that the Duchess is charming and beautiful, but inadmissible to convey that the Duchess is sexy? What is the suppressed premise here? A man can say “Not bad” so long as he has no impure thoughts? “It is trite learning,” says the old Common Law maxim, that the thought of man is not tryable, for the devil himself knows not the thought of man.”

Trite learning, folks.

What is going on with American women? And men, for that matter? Have they seriously convinced themselves that there is such a thing as a normal man who looks at a beautiful and charming woman and fails to think, “Man, I’d like to bang her?” How have they neglected to notice this most obvious of truths?

Ladies, I hate to break this to you, but that’s what men think when they look at a beautiful and charming woman. So what? Why is this his employer’s business? Why is it our business? How can we be, in 2020, so affronted by a fact of nature?

It is certainly true that it is in poor taste to discuss one’s sexual yearnings in public, just as it is in poor taste to discuss one’s bowel movements. But “intimidating, hostile, and offensive?” Why would women suddenly find the longing we arouse in men, one of the great sources of our power over the poor beasts, to be intimidating, offensive, or hostile?

You do realize that’s why they open our doors, build our homes, and rescue us from burning buildings, right?

SATAN IN YOUR DAYCARE

Sexual hysterias, as the Salem witch trials suggest, are a venerable American tradition. They are hardly unique to America, but given the pride we take—and ought to take—in our Constitution and Bill of Rights, in our Enlightenment heritage, in our modernity and our sophistication, they are a disconcerting reminder that we are rather more primitive than we care to admit. Many among us now fret that savages who “lack the habits of democracy” will penetrate our virgin border and impregnate us with their jungle primitivism. To make this case with a straight face, you must deeply believe that Americans are never, or only very rarely, given over to jungle primitivism. But it is not so. America suffers recurrent outbreaks of hysteria, particularly about sex or sexual purity. The habits of mind involved are those of the savage, not the civilized.

These recurrent outbreaks have had tragic consequences in very recent memory.

Malden, Massachusetts, is about eleven miles away from Salem. In 2001, the Massachusetts parole board quietly but unanimously recommended commuting the sentence Gerald Amirault, who had been in prison for fifteen years. In rendering their opinion, the parole board was not allowed to revisit the question of Amirault’s guilt. He had been convicted of molesting and raping eight children at his family’s day care center. Some forty children had described the way they were tied to trees, sexually penetrated with knives, and tortured by a “bad clown” in a “secret room.” They ranged in age from two to four. No corroborating evidence at all supported these allegations. One child claimed she had been assaulted not only by the accused, but by a robot; another claimed it was R2D2.

Prosecutors told the jury to “believe the children.”

The daycare hysteria began in 1983, when a clearly unstable woman accused Raymond Buckey, son of daycare owner Peggy McMartin Buckey, of sexually assaulting her child. When police told other parents of these charges, more than 208 children “came forward” (a phrase that should sound familiar) with accounts the sexual violence they had endured at the hands of the Satan-worshippers at their daycare centers. One American community after another then discovered, to the horror of all, that their children were being ritually abused by Satanists. Hundreds were sentenced to consecutive life sentences.

Children told stories of being taken to outer space in hot air balloons, of other children being dismembered in front of them and fed to sharks, of witches flying around the classroom on broomsticks. “Believe the children.”

Juries were under massive pressure to convict; subsequently many jurors reported that they had simply given in to pressure from other jurors despite thinking, “There is no evidence of this.” This was one reason people started looking at the convictions more closely: The jurors had guilty consciences.

The accused were sentenced to multiple successive life terms—even when there was no corroborating physical evidence of abuse, no adult had witnessed anything of the kind, the children were all seeing the same four psychotherapists, and the children were testifying that their teachers had killed their classmates (of whom none were missing).

The parents were convinced that they remembered their children’s behavior changing, even though no record, no witness, not one bit of evidence, indicated that they had these suspicions at the time of the alleged abuse: They remembered their children’s behavior changing, but the records suggested not one of them asked a physician about it or told anyone who might be able to corroborate their memories. It was only after they were told that their children might have been abused that they remembered their children’s behavior changing.

In Salem, those accused of witchcraft were presumed guilty. The only evidence presented against them was an accusation. Likewise the daycare panic. The only evidence presented against the accused were allegations from children. Children at the Little Rascals day care in Edenton, North Carolina, testified that other children had been ritually killed, thrown off boats into shark-infested water, and taken to outer space in a hot air balloon. The children had all been coached by the same therapists, as had their parents. The daycare workers were tried and convicted of rape, sodomy, intercourse in front of children, forcing children to have intercourse with each other, conspiracy, photographing sexual abuse, and urinating and defecating in front of children. All these convictions were—years later—reversed on appeal.

While the alleged abuse was occurring, no parent noticed anything unusual about their children’s behavior. After having their memories repeatedly refreshed in therapy, they all converged on the same portrait. Children’s advocacy groups created so much pressure that it was nearly impossible to find experts willing to testify to facts known by everyone who’s encountered a child. Children fabricate stories. They don’t have a good grasp on what’s real and what isn’t. They may readily be persuaded to believe in Santa Claus. They will eagerly repeat what you tell them.

The courts were so concerned about protecting children from the trauma of testifying that defense lawyers were forbidden from questioning them vigorously. The prosecution was allowed extraordinary latitude in coaching the children for trial. Some jurors said privately that they doubted the charges, but feared being ostracized. In the end, said juror Dennis Ray, “the children were convincing.” It was the longest and most expensive criminal trial in the history of North Carolina. It was a coached, therapist-induced panic and a travesty.

Those who suggested evidence must be weighed, or due process observed, were met with scorn from those who insisted the accused were guilty. Lawrence Wright followed a case of alleged sexual abuse and satanic ritual in Thurston County, Washington, for the New Yorker—a publication that appears to be institutionally incapable of remembering its own reporting. The under-sheriff for the county, Neil McClanahan, said, “Our survivors are very traumatized. To question their credibility would cause them to be re-traumatized. They’re so fragile.”

We have heard this same claim over and over of late. We must not in any way challenge the account of any woman who claims to be the victim of a sexual impropriety, however defined, because this will “re-traumatize” them.

Since then, almost every conviction associated with the daycare panic has been overturned. It is now widely understood that Americans experienced an outbreak of mass hysteria. There is no other explanation, unless we are prepared to believe that Satanists seized control of America’s preschools—at which point, we may as well accept that witchcraft immiserated Salem and be done with it.

As The Wall Street Journal wrote shortly before Amirault was released,

… the recognition that this prosecution—and other child abuse cases like it around the country—was built on concocted testimony has become widespread. So widespread that it is now the sort of thing studied in colleges and universities. The 49-year-old Mr. Amirault is about to finish his liberal arts degree in prison. Not long ago he had the surprising experience of opening a sociology textbook, and finding there—in a list of hysteria-driven prosecutions—the Amirault case. Things have certainly come far since the day he was carted off to do 30-40 years, a despised cast-off from society.

Wouldn’t it be nice to think things had “come far?” But that’s not how it works. It works like this: We forget it completely, then we do it again.

ENTER THE WOMEN

None of us truly understands the haunted house of the human soul, but an economic, sociological, and psychoanalytic account of these panics is more plausible than the idea that Satan possesses Americans at moments of socioeconomic stress. (The latter isn’t such an insane hypothesis, though. It’s true that the theory doesn’t fit the evidence, we can’t use it to make reliable predictions, we don’t understand the mechanism by which it works, and it can’t be falsified. But let’s not pretend these problems are unknown to economists, sociologists, and psychoanalysts.)

Start with the economic. Base determines superstructure, Marx observed, and he had a point:

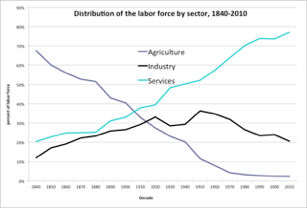

The small, upward tick in manufacturing, mid-century, is attributable to the Second World War. That artifact aside, we see that American manufacturing peaked in 1920. The graph tells a clear story.

The 20th century saw the complete transformation of the American labor force. At the beginning of the century, Americans were chiefly employed in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors. We are now almost entirely employed in the service sector. Until recently, this was the working definition of economic development: A country progressed—in a Whiggish way—by moving from agriculture to manufacturing to services, at which point it was developed.

The entrance of women into the American labor force in the 20th century has been called the Quiet Revolution. It took place in four phases. At the beginning of the century, women married early, were defined by their marriages, and entered the workforce only in the event of a catastrophes such as the death of their husband.

The First Phase—from the turn of the century to the 1930s—saw the emergence of the so-called “independent female worker.” Typically young, unmarried, and uneducated, she usually took jobs seen as suitable for women—teaching and clerical work—and exited the workforce when she married.

The Second Phase—from the 1930s to the 1950s—saw women staying in the workforce after marriage. Why? Because the growth of the service-sector created demand for clerical work, and the movement toward compulsory high school education, essential for creating a workforce suited to service sector employment, created demand for teachers. Marriage bars—policies mandating the firing of women once they married—were widely eliminated.

The Second World war not only brought five million women into the workforce, it exposed them to entirely new forms of work. Some 350,000 women joined the military. Absent soldiers left a gap in the labor force; it was filled by women, who took jobs in factories and defense plants.

By 1943, women formed the majority of employees in the aircraft industry. Women also took over the service sector jobs the men at war had left behind. Rosie the Riveter discovered, to her surprise, that contrary to received wisdom she was good at these jobs. She discovered, too, that financial independence meant freedom.

Scholars describe the period from the end of the war to the 1970s, the Third Phase, as the “roots of the revolution.” When men returned from the war, they wanted their jobs back. Women were admonished to return to their “rightful place” in the home. Although 75 percent of women reported that they wanted to keep working, they were laid off in large numbers.

But it was too late. The genie was out of the bottle. Women had seen that certain things previously thought impossible were entirely possible. Their expectations and yearnings had changed. Even though they were largely re-consigned to women’s work—as secretaries, teachers, nurses, librarians—women struggled to re-enter the workforce.

Then came the revolution.

FRIEDAN V. FREUD

It is called the sexual revolution, but the term places excessive emphasis on the distinctly sexual aspects of the revolution. The sexual revolution was made by women avenging their mothers’ frustrated lives. Their mothers had tasted the forbidden fruit, they had too-briefly seen that another life was possible and so much more interesting than child-rearing and homemaking. Their mothers had just as promptly been exiled from the garden, the taste of the apple still on their lips.

In 1957, Betty Friedan conducted a survey of her former Smith College classmates for their college reunion. Friedan had given up her own career to raise children. She found, to her surprise, that her classmates were unhappy in their rightful places; none of them quite understood why, nor did they realize they were not alone in feeling this way. They led lives of material comfort; they had children. Why were they dissatisfied?

“Part of the strange newness of the problem,” she wrote, “is that it cannot be understood in terms of the age-old material problems of man: poverty, sickness, hunger, cold.” Women, she concluded, were like men governed by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Motherhood, in itself, was insufficient to provide what Abraham Maslow called “self-fulfillment.” She insisted that women could no longer ignore the voice within that said, “I want something more than my husband and my children and my home.” Indeed, she concluded, the life of an American housewife was “a comfortable concentration camp.”

In Chapter Five, she took on Sigmund Freud. Freud admired John Stuart Mill and shared his liberal instincts, even describing him as “perhaps the man of the century who best managed to free himself from the domination of customary prejudices.” But he found Mill’s notions about “female emancipation,” indeed his views of women in general, both naive and preposterous. In a letter to his fiancée, Freud remarked offhandedly that Mill’s feminism—proto-feminism, more precisely—must devolve from his inexperience of women and his sexual repression. “His autobiography is so prudish,” he complained, “that one could never gather from it that human beings consist of men and women and that this distinction is the most significant one that exists.”

(Cited in Bruce Mazlish, “James and John Stuart Mill” (Routledge, 2017, pp. 333-334)

Friedan concedes what many now forget: Freud’s genius and immense perspicuity, the critical role he played in emancipating women from repressive Victorian sexual strictures. Freud now occupies an intellectual no-man’s land. The right reviles him precisely for the contributions Friedan acknowledges. The left, thanks in part to Friedan, denounces him as a misogynist. Few bother now even to read him. A shame. A generation has now grown up without the benefit of Freud, who was, as Friedan acknowledged, “a most perceptive and accurate observer of important problems of the human personality,” and without whom observers of the human personality are sure to be more baffled than strictly necessary. For that matter, few read Friedan anymore: Most are already quite sure what they think of her, and of Freud, and see no reason to grubby their minds by reading either of them.

Friedan did not argue in favor of throwing out Freud altogether. She observed that Freud was a creature of his time and milieu, who saw women “as childlike dolls, who existed in terms only of man’s love, to love man and serve his needs.” Freud’s “unconscious solipsism,” she wrote, was of the variety “that made man for many centuries see the sun only as a bright object that revolved around the earth.” An understandable mistake.

It was not Freud she deplored so much as his followers— “popularisers, sociologists, educators, ad-agency manipulators, magazine writers, child experts, marriage counsellors, ministers, cocktail-party authorities”—who deployed neo-Freudian jargon to clad the cult of the “feminine mystique” in pseudoscientific authority, telling women their failure to find fulfillment in housewifery was evidence of their “masculinity complex.” All too many women, Friedan wrote, were smart enough to be miserable with their lives, but not educated enough to tell Madison Avenue to take this patronizing pseudoscientific gibberish and shove it in their anal fixation.

She was correct to see flaws in Freud’s work and absurdities in his popular interpretation. She did not suggest Americans jettison Freudian thought entirely; she was too thoughtful for that. But it happened nonetheless, and we are not better off for it.

THE FEMALE EUNUCH AND THE VACUUM CLEANER

Then, in 1970, Germaine Greer wrote The Female Eunuch, expressing the collective rage and resentment of her mother’s generation—the Friedan generation. She argued in no uncertain terms that women hated the lives that they were supposed to love. They hated pregnancy and childbirth and taking care of babies. They found it deadly boring. They felt entombed. They wanted real, meaningful, long-term, gainful employment, and not as librarians, either. They wanted to be doctors, managers, lawyers, in charge. This was the decade in which women ceased to major in education and began to major in business and science.

Other social factors hastened women’s entry into the labor force. By the late 1960s, the United States had achieved full electrification. Labor-saving devices such as the vacuum and the washing machine had been invented in the 1920s, but only became available to the mass market in the 1960s. These goods improved in quality and declined in price by 8.3 percent per year, even as real wages rose.

By the end of the 1960s, these devices could be found in every household, dramatically reducing the overwhelming burden of housework. In a paper titled “The Effect of Household Appliances on Female Labor Force Participation: Evidence from Micro Data,” economists Daniele Coen-Pirani, Alexis León, and Steven Lugauer persuasively argue that it was not the Pill but the washing machine that liberated women: “According to our estimates,” they conclude, “household appliances account for about forty percent of the actual increase in participation by married women during this period of time.” Other researchers have argued that technological advances in the household sector help to explain the increase in the divorce rate and the decline in the marriage rate, too.

For those unpersuaded to leave their homes by the washing machine, there was the Pill. Even in 1966, Massachusetts had amended its law declaring that the provision or exhibition of contraceptive devices and the printing or dissemination of information about them were “Crimes Against Chastity, Morality, Decency, and Good Order,” punishable as a felony by up to five years in prison. The 1970s saw women gain widespread access to contraception when the Supreme Court ruled, in Baird v. Eisenstadt, that there was no reason they shouldn’t. Nor need unmarried women—at the peak of their fertility—require anyone’s consent to obtain contraception. Here again, a war abroad changed the role of women at home. No civilized society would send boys to war; therefore, 18-year-olds sent to Vietnam must be men. The 26th Amendment was ratified in 1971. And if unmarried 18-year-olds were old enough to go to war and to vote, they were surely old enough to make their own decisions about contraception. The court’s far more controversial ruling about abortion followed from the precedent of Baird.

One of the most cited lines in The Female Eunuch was this: “Women have very little idea how much men hate them.” But Greer was mistaken. Men did not hate women; they misunderstood them. And until the rise of the service sector and the Second World War, women had misunderstood themselves. Not until “work” was separated from “physical strength” did it become obvious that the standard divisions of the nuclear family—he works, she brings up the children—were not the only ones possible.

Now, it seems, men are becoming all too aware how much women hate them.

But why?

This is a six-part essay. Continue here to Part III.

As a high schooler in the mid-60’s I recall my astonishment at hearing that in Scandinavian society it was not unusual that male members of married couples might voluntarily take on the role of “house-husband”, doing housework and looking after children, while their wives pursued their careers. As I recall, I presumed that a) Scandinavian men were not concerned with income or social status that come with earning a steady income and having a prestigious job, compared to Americans, and b) Scandinavian women must be paid far better than American women. My mother, a widow, supported us with a full-time career-track job, and earned a salary that was somewhat less than that earned by her male counterparts. I believe both suppositions were at least as true as any generalization can be.

Note to self: This is part II.