I hoped very much that these Twitter summits would stay boring, but alas, they have not. Below is the beginning of Arun Kapil’s outstanding summary of where we are.

The French presidential election: two days to go

Arun Kapil

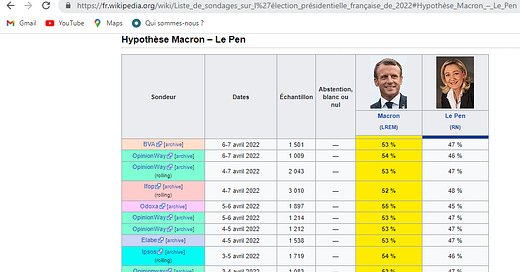

A week ago I expressed anxiousness over the state of the race and the very real possibility that Marine Le Pen could win on April 24th. Today I rate the chances of that at 50-50. Almost all the polls now have a maximum six-point spread between Emmanuel Macron and MLP, with one earlier this week showing a bone-chilling three-point squeaker for Macron. And the momentum—the Big Mo’—is clearly with Mme Le Pen, as given the way election campaigns work in France, there is little that can stop it at this stage. If this campaign were happening à l’américaine—with American-style practices—the Macron camp would be flooding the airwaves with negative ads attacking Le Pen for her manifold weaknesses, extremist positions, and the dangers of her acceding to the presidency of the French Republic, particularly at this grave moment for Europe and the world (e.g., informing voters that if the Putin-friendly Le Pen is elected on April 24, she will immediately assume the presidency of the Council of the European Union to the end of June, and for voters to meditate on this). And Macron surrogates and other politicos and commentators would be sounding the alarm in the media.

But this is not possible in France, as campaign advertising on television is heavily regulated (a good thing) and with no tradition of negative attack ads (not a good thing), and now that we are in the official campaign period, the law mandating strict equality of coverage on television and radio for all presidential candidates—there are twelve—has kicked in, meaning that oddball Jean Lassalle and the laid-back post-Trotskyist Philippe Poutou, both polling in the very low single digits and with no manifest wish to actually be elected president of the Republic, are entitled to as much mention on TV, including in prime time, as are Macron and Le Pen. I had a whole AWAV post exactly ten years ago railing on against this ridiculous French law, which, in effect, deprives the electorate of serious debate and examination of issues in the final stretch of the campaign, and at precisely the moment when many voters are beginning to tune in. So Macron’s hands are tied in trying to stem the Le Pen surge, a surge that he and his campaign clearly did not anticipate.

Not that Macron would necessarily know how to effectively respond even if he had all the time in the world. His deficient political skills are continually laid bare, most lately in his refusal to participate in first-round televised debates, arguing that, in addition to Ukraine and his other presidential responsibilities, the deck would be stacked against him in having to respond to the attacks of the eleven other candidates but in exactly the same allotted time as each of them. His reasoning is not entirely without merit, except that to the median voter in the Meurthe-et-Moselle or Tarn-et-Garonne, it just looks like he’s dodging debate. So instead of appearing on France 2’s two-hour campaign special on Tuesday evening and in the presence of five other candidates—though they didn’t debate one another—the Macron campaign supplied France 2 with footage from his Paris rally last Saturday—his only such campaign event—to use up his allotted temps de parole.

I attended the rally, which was held at the Paris La Défense Arena in Nanterre (a half kilometer past La Grande Arche), the largest domed stadium in Europe, with some 30,000 Macron fans in attendance. Very much a CSP+ crowd: educated, professional (or soon to be for the younger ones), well-off. La France qui va bien—the France that is doing well for itself—and that is not afflicted with cultural resentments or identity crises. Macron’s base. Les premiers de cordée. All the top macronistes were there on the stage—Edouard Philippe, Jean Castex, François Bayrou, Christophe Castaner, Manuel Valls et al.—but none of them took the microphone. There were no warm-up speakers. Just Macron, who spoke for two hours and ten minutes (with six teleprompters), which is long for one who is not only merely okay as an orator but doesn’t have anything really compelling to say.

Much of the speech consisted of a laundry list of his presidency’s accomplishments, mostly small bore stuff that no one likely remembered five minutes later, or of promises to tackle problems in his second term but that have loomed or festered for years, such as the many crises in the health care system, to which one wanted to ask where he was on these issues in the three years before the pandemic hit. I spent much of the speech scrolling through Twitter and Facebook, only half paying attention. There was regular applause but little of it thunderous. A contrast with Macron’s 2017 Paris rally. At one point he said “il faut travailler plus…” I was waiting for him to finish the phrase with “pour gagner plus” but he didn’t (had he done so, his poll numbers would have surely tanked several points). Tepid applause. Telling people they’ll have to work more if he’s reelected: a sure-fire way to fire up the base and win votes while he’s at it! He got better in the latter part of the speech, particularly when talking about Europe. One of the very few positive reasons—if not the only one—to vote for Macron in the first round.

But if Macron is finding himself in a fragile position vis-à-vis the extreme right-wing Marine Le Pen, perhaps he should look in the mirror to understand why. He is, as Mediapart’s Ellen Salvi put it, trying to put out the flames that he himself stoked. During the 2017 campaign, Macron ran as a liberal in both senses of the term: economic (more market oriented) and political (in the way Americans understand it), with the latter leading him to adopt a progressive-sounding rhetoric on immigration, laïcité, the legalization of cannabis, and other such societal issues. But there was no positive action on any of these once he was elected and two years into his quinquennat—after the country had been rocked with social contestation over the reform of the Code du Travail and then the Gilets Jaunes, and with the battle over pension reform looming—somehow he decided, comme ça, that the French public was less concerned about economic and social issues than “regalian” ones—the “four Is”: immigration, insécurité, Islam, identity—and that these would drive upcoming election campaigns.

And so he did a 180°, lurching to the right not only in his rhetoric and legislative action on civil liberties and the “four Is” but also in symbolic gestures and signals; e.g., publicly palling around with dyed-in-the-wool réac Philippe de Villiers, spending 45-minutes on the phone with Eric Zemmour and then soliciting his perspectives on immigration, exchanging textos with the Fox News-like CNews star host Pascal Praud, granting interviews on immigration and identity to the hard-rightist weekly magazine Valeurs Actuelles (a cross between National Review and Breitbart), et on en passe. The French hard right, as with its Trumpian kindred spirits outre-Atlantique, has been waging a full-throttled culture war—against something called “wokeisme” and “islamo-gauchisme”—and with Macron eagerly jumping on the bandwagon.

Macron’s rhetoric and action since 2017 on economic, social, and “regalian” issues have made him, in the words of sociologist-historian Pierre Rosanvallon, “the central figure on the French right.” There is nothing in Macron’s rhetoric today that recalls his roots—albeit shallow—in the Socialist party or youthful support of Jean-Pierre Chevènement, the longtime chef de file of the PS’s left flank before quitting the party in the 1990s. (For the record, Chevènement, now into his 80s and retired from politics, has declared his support for Macron and rejected the notion that he is on the right). Macron has manifestly decided that he does not need to appeal to voters of the left, that he has maintained his hold over the 2012 François Hollande voters who defected to him in 2017—who are either content with Macron or feel, not unreasonably, that there is no credible alternative to him—and that a sufficient number of left voters who are hostile to him will nonetheless hold their noses and cast his ballot in the second round to block Marine Le Pen. A risky assumption, if not a dangerous one.

As for the left, Jean-Luc Mélenchon has been climbing in the polls but, at 17 percent, is six or seven points behind Le Pen, who has been climbing even more. Paris-based journalist Cole Stangler has a good article in Foreign Policy arguing that “A Mélenchon vs. Macron runoff would be good for France,” but it looks most unlikely at this point that JLM will be able to overtake MLP to qualify for the April 24 second round. …

Read the rest at Arun with a View.

We’ve also invited Anne-Elisabeth Moutet to join us, and here is her latest column, also superb, about this race. Like Arun, she blames Macron for Le Pen’s remarkable comeback:

Three months ago, Marine Le Pen’s political future seemed smashed into irrelevance by the rise of Eric Zemmour. She was past it, a tired war horse with no project and a quasi-bankrupt party, watching her closest National Rally associates being shaved off one by one by Zemmour’s seemingly irresistible promise of rebuilding the French Right in his image, a mix of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz and De Gaulle’s 1950s RPF. …

…. But most of all, Marine Le Pen has been helped by Emmanuel Macron. Discontented voters chose him five years ago to spite the other, older, hackneyed candidates—a populist reflex for a man who used populist means for decidedly non-populist policies. His victory was built on the cold-eyed destruction of traditional political parties Left and Right, and he never stopped to consider the effect on public life. …

… Like the spoiled child he has been for all 44 years of his charmed life, political and personal, Macron has never had to face consequences for his decisions; for him, turning the French Republic into an atomised wasteland of individuals matters not one bit. (He will be remembered as the Houellebecq President.) Under his presidency, France was shaken by popular revolts such as the Gilets Jaunes who felt no one was representing them in a country of weak unions and even weaker parties. His handling of the Covid crisis wasn’t much worse than that of any other government, but it was characterised by a range of baroque and contradictory measures, always presented as the réalité du moment, without ever acknowledging what had come before.

Read the whole article, here. The conversation will be greatly enriched for having her perspective.

Arun’s verdict on this predicament—that Macron brought this on himself—is actually quite similar to Anne-Elisabeth’s. (Though I’m sure neither will admit this.) It differs from mine. I don’t find Macron insufferable. I think he’s done a good-enough job. I think the French public is insane—out of its mind—even to consider a Le Pen presidency as a solution to any of its problems. In the context of the war in Ukraine, the idea is quintuply insane.

Should she win, I would not blame Macron. I would blame France. I discussed this at some length in this essay, “The Problem with no Name”—but I would note that France is hardly alone in this species of insanity:

Something about life in modern democracies really bothers people. Let’s call it the Problem that Has No Name. There are many theories about what the problem really is. The most popular involve wage stagnation, inequality, globalization, capitalism, the digitalization of the economy, social media, immigration, the disappearance of traditional venues for social life, the transformation of gender roles, the decline of religion. Some combination of these things infuriates people.

Whatever the problem really is, obviously it is complex. But the world around, voters have recoiled from the idea that their problems are complex. In one democracy after another, voters have decided the best person to solve these problems would be a brutish authoritarian.

Whatever the problem really is, it is either caused by, or the cause of, a blackout of rational thinking. The Gilets Jaunes embody this. …

Anyway, having read those articles, you’ll be well prepared to join us as we try to figure out just where this is headed and what it means. It’s the last thing I wanted to be worrying about right now—I thought Macron had this in the tank—but here we are.

Do join: Here’s the link.