Political Polarization, Foreign Policy, and Iran

Partisanship protects us from thinking things we do not wish to think

Causation and Responsibility in International Relations

Like everyone, I’ve been glued to the news from Iran. But man, have I been dismayed by the American commentary about these events. Have we always been this dumb? Or is our political polarization turning us all into mental cripples? Domestic politics now seem to be the prism through which we see everything, even events that can’t remotely be explained in terms of our domestic divisions.

The majority of us now view the world through a partisan lens, if you could call it that, even when it brings nothing into focus. It’s almost as if we’ve forgotten there are other ways to think.

Even people I know to be smart have spent the past week saying things that they couldn’t possibly really believe. I’ll show you what I mean point-by-point (at the risk of losing all my friends) so you can see just what I mean.

But first …

THE PAYWALL OF HONOR RETURNS

I could not be more grateful to those of you who have contributed, which you can now do in many easy, one-click ways. You can contribute on GoFundMe, which I love because I get the money immediately and I see the counter go up, up, up. Or you can contribute via PayPal, which doesn’t make the counter go up, but the money is just as gratifying, and I get (slightly) more of it. So rationally, I suppose it’s better.

But those of you who have become my patrons on Patreon are especially dear to me these days, because if you become my Patron, Patreon bundles you with other patrons and then pays me a lump sum at the end of the month—just when I’m running out of cash. It always surprises me. I never include reader contributions in my budget, because I can’t be sure of them. So when I get that bonus at the end of the month, it seems like a genuine miracle and a direct response to an unuttered prayer.

Theological aside: If you’re wondering why the prayer’s unuttered, it’s because I figure God would just be infuriated if I asked Him, outright, to pay my bills. You can pray for good health, a strong mind, and the discipline to work harder, right? All that’s fair game. But if I say, “Please, God, just pay off my Visa card,” I figure He’ll smite me like He smote Janis.

Nonetheless, for several months running now, the amount Patreon has sent me has been almost exactly the amount I’ve been in the red—and I’ve had a sense of divine intervention every time. God saved my hapless ass again. Now, I don’t know if this is really how the universe works, but I am very grateful for it—both to you, my patrons, and to Providence.

The next section—up to the jump—is for those of you who have contributed, in any amount, ever. If you haven’t contributed, please avert your eyes and scroll down. Alternatively, you can forward this newsletter to the ten people you think would most enjoy it. That earns you a free Day Pass.

In fact, I’d surely appreciate it if all of you forwarded this newsletter to the ten people who’d most enjoy it. Would you mind doing that?

Oh, one more thing! I’ve been wondering why none of you ever leave comments in the comment section. I thought that was a shame, because so many of you send me such interesting emails. The e-mail I receive from my readers tends to be more interesting (and often much better-informed) than nine-tenths of what you’ll read in the news today. I keep meaning to publish the best ones, but they take up a lot of space, and you say you hate long newsletters. The obvious solution is for you to post your emails in the comments section, right?

But I finally figured out why you don’t. You can’t. Substack only enables the comments feature for readers if I charge them to read the newsletter.

I’m not going to do that, but what I could do is enable the paid subscription feature, at the base rate, so that those of you who want to can use the comments section. You can meet each other. You’d like each other. I’ll keep everything I write here free, though, save for what I put behind the Paywall of Honor.

So if you receive an e-mail asking you to pay to read this newsletter, don’t be alarmed—it isn’t some kind of bait-and-switch. The newsletter will always be free.

(Also, I just changed the system by which I import my e-mail addresses. I’m not quite sure if I’ve done it correctly. I may have imported a few addresses I didn’t mean to add. If you don’t wish to receive this newsletter, just scroll down and press “Unsubscribe.” No need to send me an e-mail telling me how much you hate me, my newsletter, my country, or the Jews.)

WHEN DOES A FOREIGN POLICY SUCCEED?

I still have absolutely no idea what will result from the assassination of Soleimani, and neither do you, and neither does anyone who claims to know. We can’t know yet. This story isn’t over.

When, you may be asking, will we know? Or perhaps you’re not asking, but as I thought about it, I realized the question was interesting. Time is continuous, so what does it mean to say a historic event is over, that is to say, discontinuous? Let’s think about this abstractly for a moment. I’ll show you how it’s practically relevant by the end of this newsletter.

Would all agree that we know the fate of the Roman empire? Or the outcome of the Thirty Years’ War? Yes. Now, this is not to say these events have no contemporary ramifications: To the contrary, every aspect of the contemporary world has been shaped by them. Still—they’re over. We know how the story ended. It’s not too soon to say that Rome fell. It’s not too soon to say the Thirty Years’ War killed eight million people and replaced the primacy of God with the modern nation-state.

We’d probably all agree, too, that it’s too soon to say what the long-term impact of China’s rise will be, or how artificial intelligence will transform the world. The verdict isn’t in. It can’t be. If there are historical or political laws that govern these processes, we’re nowhere near understanding them well enough to make useful, reliable, and accurate predictions.

Of other events, most of us would agree that it’s too soon to tell, as Zhou Enlai did not, actually, say of the French Revolution. That was a mistranslation; in fact, he’d been asked about the 1968 student revolts. But the remark entered history as it did because it was so much more interesting as misreported. It captures the Revolution’s ambiguous legacy perfectly.

It’s not too soon to tell whether the Bolshevik Revolution failed. It did. It was too soon, however, to celebrate the end of history in 1989, or to declare the inexorable victory of liberty. Tyrannies around the world, it turned out, were not about to fall of their own accord, nor even gently to topple should we give them a nudge.

So what exactly do we mean when we say that a historic story is over? I propose it means this: We can say it when enough time has elapsed—or when events sufficient have transpired—that we may reasonably evaluate it in the terms of the objectives of the actors who willed it.

At the end of the First Battle of the Marne, it was too soon to tell who would emerge victorious from the Great War, but not too soon to say that no one’s initial objectives— be they to chasten Germany in a jolly war that would be over before Christmas, or to ensure security for the German Reich in west and east for all imaginable time—would be met.

Here’s an important point. Observers of contemporary Europe often remark upon the irony that at last, Germany has, more or less, achieved the war aims articulated in the 1914 Septemberprogramm. In some sense, this is because of the course of action undertaken then by Germany’s industrial, military, and political leadership. Were it not for the First World War, there would have been no Bolshevik Revolution, no Second World War, no Cold War; Germany would not have been rubbled, divided, and occupied; the United States would not have become a European hegemon, there would be no European Union.

Does this mean we should assign to these men the credit for achieving Germany’s war aims? Were Moltke, Hindenburg, and Ludendorff the most visionary generals in human history? Of course not. Had they truly understood the consequences of their decisions, they would have killed themselves.

So it is possible for an agent to be the cause of event y—in the sense that had he not performed x, y would not have happened—even as it is possible for us to say that he does not deserve the credit—or the blame—for y.

To make this point even more clear, try this thought experiment. Let’s say I keep piranhas as a hobby, and you are a crackhead. You break into my house to steal my television, but because you have the shakes, you trip over my ocelot, fall into my fish tank, and find yourself attacked by ravening piranhas. I return home just in time to fish you out and race you to the hospital, but alas, you acquire a mysterious hospital-borne infection. Your immune system is so ravaged that you perish from it.

In one sense, it may be said that I caused your death. After all, had I raised goldfish and not piranhas, you would still be alive. Nonetheless, no court of law would find me criminally negligent.

Conversely, imagine you’d extricated yourself from the tank—nibbled, but still alive— and let’s say my salsa class was running late, so I missed the whole drama and I’m none the wiser. You resolve never touch the crack pipe again, have a spiritual awakening, go to medical school, and dedicate your life to discovering the cure for cancer. If you succeed, can I take credit for curing cancer? After all, a dunk in a goldfish tank would hardly have scared you straight, right?

Of course not. When we assign moral credit or blame to an actor, we suppose two things: First, that the actor intended the consequences that ensued; second, that it was reasonable to expect these consequences.

This isn’t difficult, when I put it like that, is it? That nearly all of America is now incapable of connecting these circuits when discussing Trump and Iran can only be explained by the stupidity partisanship has induced in us.

THE IRAN RORSCHACH TEST

The downing of Flight 752 introduced a raft of new uncertainties. Protests against the regime resumed much faster than I expected.

This Twitter thread suggests many of the problems with our national discussion about what these protests mean:

Look at the way partisanship leaves us unable to think rationally even about basic things like causation and responsibility.

Sure. And if I’d raised goldfish, you’d still be alive. Or I’d have cured cancer. Same argument.

But just as preposterously, many Trump enthusiasts are equally certain these protests are a great victory for Trump and the United States. How? Why? By what mechanism? One friend wrote that the protests in Iran represented “a good day for liberty.”

Despite the political and media hysterics of the past week, it is very difficult at this point to argue that the killing of Qasem Soleimani was anything but a net positive for the United States … and eventually, for the people of Iran whom he so prodigiously killed.

Soleimani is dead, which is cause for celebration, because it is just. Justice is not the same thing as liberty, though—and certainly, it can’t be used to predict the future. I suppose the words “at this point” are carrying a heavy load here, but anyone who has paid attention to Iran—as this friend has, in fact—knows what’s likely to happen. Those protesters will be arrested, tortured, raped, and killed. How is that good for liberty? How is it a net positive for the United States?

There’s only one way this can be good for liberty and a net positive for the United States: If the regime falls, and is replaced by a better one, as a result of these protests. In no other imaginable scenario are these protests good for liberty or even relevant to the United States. Another savage regime crackdown would be another terrible tragedy. If the regime kills the protesters—and does anyone doubt it is very likely to do that?—then sprints to complete its quest for the Bomb, how would that be a victory? If it activates its murderous sleeper cells in North America (and South America, Asia, Africa, and throughout the Middle East) and kills hundreds or thousands more innocents? If it wipes out whole cities or states before meeting its own demise?

Any thinking adult knows that the latter scenarios are well within the realm of the possible. How many scenes of horror from Syria do we have to see to admit the possibility that brave people, demanding the fall of a barbarous regime, don’t always triumph?

Only partisanship can explain the eagerness to see this uncertain situation, which could truly mean anything, as something other than what it is: uncertain. It’s a geopolitical Rorschach test. If you see in these protests a vindication or a repudiation of Trump and Trumpism, you’re projecting your own partisan passions.

THE BET

Sometimes, protests preface the fall of a brutal regime. Always, actually. Even the most savage regimes do, sometimes, collapse. And sooner or later, all regimes collapse. Everything in this world comes to an end. I well remember the Soviet Empire just vanishing—and at the time, that seemed just as unlikely—more so, even. Few predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union. But that doesn’t mean this regime is apt to collapse now. Regime collapses are extremely hard to predict. We just don’t understand how it happens well enough confidently to predict them.

But when it comes to Iran, the key question really is the one we don’t know how to answer—when?—because there’s a deadline: If it survives long enough to acquire a nuclear weapon, we’re hosed.

Now, we all know, if we’re at all honest, that there is no domestic support whatsoever for a war to prevent Iran from acquiring the Bomb. Americans know too much about what such a war costs. We’ve concluded it isn’t worth it. Whether we know enough about what the alternative would cost is unclear, but our unwillingness to invade Iran and change its regime by force is a political fact as limiting upon a president as any military fact. We cannot do it. We are willing to pay to have a very strong military, but God help the Commander-in-Chief who proposes to use it to change the regime of another despotic Persian Gulf nation with a four-letter name that begins with an “i.” Every American president will be operating within this constraint. Whether or not we openly admit it, everyone knows this—including Iran. In this sense Iran won the Iraq War.

Since changing the regime by force is not an option, and given that a hostile Iran with a nuclear weapon would be a catastrophe—or at least, extremely unpopular with the American electorate—Obama and then Trump have faced a circumscribed range of policy options. Their policies toward Iran may be described in terms of a bet: Can the regime survive long enough to get the Bomb?

If you bet that it can, you get something like Obama’s policy. You can’t have a regime that wants our death and has the Bomb. The regime isn’t going anywhere. So the regime must be persuaded not to want our death.

If you bet that it can’t, you get something like Trump’s policy. You can’t have a regime that wants our death and has the Bomb. The regime is about to fall. So let’s give it a push.

Whether Trump has thought this through, I don’t know, but his advisors, it seems to me, are betting that the regime is on its last legs and ripe to be strangled.

I truly don’t know who is right. Neither do you, and neither do they. We have no way of knowing who is right. All we have are intuitions, and a very small number of us have informed intuitions. The overwhelming majority of Americans who feel strongly about this are expressing domestic and partisan sentiments about the United States, not informed intuitions about Iran.

My own intuition is that they are both wrong. I don’t believe the regime may be made less hostile—but I also doubt that it can be strangled before it acquires the Bomb. I suspect that if we want it gone, we’ll have to do what we did in Iraq. If we don’t want to do that, we’ll have a nuclear Iran.

There are solid arguments in favor of the bet that it won’t collapse any time soon. Philip Gordon and Robert Malley make the case here:

Like the Soviet Union 30 years ago, the Iranian regime sooner or later will crumble under the weight of its own failures. For the United States to try to accelerate that process by impoverishing the country and placing the regime before an existential threat is a huge gamble, unlikely to pay off. Wishful thinking about regime change in the Middle East is something we have seen before. It has rarely ended well.

Mohammed Ayoob agrees. Could This Be The Beginning Of The End For Iran's Regime, he asks? Don’t bet on it, he replies. Eventually it will collapse, but in the short-term, it will survive.

“Don’t expect regime change in Iran,” agrees Jack Goldstone, who predicts it will collapse in about 2050:

… the normal lifespan of a radical revolution—whether in France (1789 – 1871), Russia (1917 – 1991), China (1949 and counting), Cuba (1959 and counting) or Mexico (1910 – 2000)—is measured in seven to ten decades before a more pluralist, post-revolutionary government emerges.

The Islamic Republic will likely become a looser, less rigid, and more pragmatic or open at a future date. But if we look at other revolutionary regimes that survived a testing youth, that process typically takes two to three full generations. As the Islamic Republic was born only in 1979, it is likely to last at least until mid-century or longer.

The arguments they make are not stupid, and they will not become stupid if we get lucky and the regime collapses. The good money is not, unfortunately, on the side of Trump’s bet.

But it is a bet, and sometimes gamblers get lucky.

Should these protests presage the fall of the regime, Trump will certainly take credit for it. In some sense, that would be appropriate. The proximate cause of the protests was the downing of Flight 752. Trump killed Soleimani. Had he not done so, almost certainly Iran would not have mistaken Flight 752 for a military aircraft, and all of its passengers, God rest their souls, would still be alive. In that sense, Trump would have caused the regime to collapse. But in that same sense, it could be said that Trump killed the passengers on Flight 752. Are those who would credit Trump for this imaginary triumph prepared to accept his responsibility for those deaths? Are they prepared to accept it right now? I thought not.

IT’S NOT ABOUT US

But if the Iranian regime falls, it will not be because of Trump. It will be because it is a regime that’s capable of shooting a civilian airliner out of the sky and then trying to bulldoze the evidence. It will be because that regime is rotten to the core.

If the regime survives, it will not be because of Trump, either. It will be because it is a regime capable of killing as many of its own citizens as it needs to quell these protests.

As I write this, the news that the Iranian regime has opened fire on the protesters has come across the transom. That is not Trump’s fault—but this point does seem very hard for some to grasp:

Unless we invade and occupy Iran, the future of that regime is in Iranian hands, not ours. To believe that absent invading and occupying the country we have a great deal of control over what happens next is to enter the delusion of the Mullahs. We are not the Great Satan and we are not God; we can’t that change regime by force of will, or sanctions, or covert action. If we could, we’d have done it already.

INFORMATION WARFARE AND INTERNATIONAL CONSEQUENCES

I received this a few days ago from a correspondent who doesn’t wish to be named. I thought it astute.

The elimination of Qasem Soleimani, and the subsequent retaliation by Iran against American assets in Iraq, is a good window into how you can expect international conflict to proceed in the 2020s and beyond.

The deaths aren’t important. The damage isn’t important.

It’s the message.

Now, before I go any further, I need to point out—constant escalatory kinetic messaging without regard to strategy is a disaster waiting to happen. Maybe not now, maybe not tomorrow, but it’s like flicking a zippo in a room full of propane tanks—eventually, it’s going to go very poorly.

There will be cascading damage from the death of Soleimani. Loss of such an adroit secret policeman and terrorist wrangler will have effects for quite a while, but it will not mean the end of Iran any more than the death of Lavrenty Beria would have ended the Soviet Union in 1940.

I have complained for some time that the lack of a broader strategy is damaging. I would like to amend that—it’s not inherently a lack, it may be poorly implemented strategy, but I’d like to present some of America’s current strategic objectives that are odds with each other:

Support Israel

Withdraw from the Middle East

Fight Islamic terrorism

End the Forever Wars

Show strength in the face of a rogue state acquiring nuclear weapons

Appease North Korea

Richard Nixon’s Madman Theory worked, primarily, because it was all driven towards a singular geopolitical strategic goal: the defeat of the Soviet Union, whether that meant teaming up with China, abandoning allies, enabling totalitarians, upping foreign aid, expanding conflict, or negotiating peace. He ranged across the spectrum of options, but it was all in the service of defeating a single adversary.

There is no such unity to our current actions. The primary adversary of the United States (and indeed, of open society) is the People’s Republic of China. Secondary adversaries include, but are not limited to, Russia, Iran, the DPRK, and non-state actors such as al Qaeda.

The PRC has very little stake in Iran. They’re happy to sell the Iranians weapons, and trade intelligence on the US, but it’s not an area they’re watching very closely.

The DPRK is watching closely. Iran and the DPRK are quite similar—regional powers concerned about 1991-style intervention or 2003-style regime change. The DPRK has nukes. Iran does not—yet.So, where does this leave the Iranian response to all this?

Iran has been watching the same news as the rest of the world (plus their own private intelligence reports). They know the US does not like Iran, but they know that the president is not moving along any clear trajectory. The president bluffs frequently, acts rarely. The elimination of Soleimani is the exception, not the rule. The rule is to call off military exercises, re-route deployments, cancel strikes (or arrange for strikes to be minimal, as at Tabqa Airbase in Syria). Iran understands that this is a messaging game, not a body count competition.

And so they chose to send a message.

I’m uncomfortable speculating too much about the specifics of weapons used, but at an open-source level, I can tell you that they were a small number of short range ballistic missiles, or SRBMs. They were probably older models, with newer guidance systems on them. This is a common practice among adversaries that cannot afford to fully upgrade their missile arsenals—you modernize the old stuff. They may fly slow, obvious routes easily intercepted by ballistic missile defense systems, but they hit with good accuracy (well, to a given value of good—the circle of probable error on these systems ranges widely and I’d be more comfortable not publicly speculating about it). The damage they did was minimal, but it showed that the Iranians can target air bases without much trouble. The messaging here is not to the United States nearly so much as it is to others:

To Israel and Saudi Arabia: “We can hit what you have and what matters to you. We can do so without leaving our own country.”

To the DPRK, Russia, and China: “The SRBM-model national defense is valid. Develop, and sell us, more, and we’ll be well-equipped.”

To the Iranian people: “We have answered our adversary’s aggression with a strike so powerful they have been cowed into inaction and going back to their beloved sanctions rather than risk our military wrath again.”

The last, it needs to be said, is bullshit—it’s an ineffectual strike on air bases with a laughably low raid size—but it’s a message that’s difficult to refute without the US doing the wrong thing. The right thing here is to de-escalate, but this goes back where I started: What’s the strategic goal? The conditions on the ground haven’t changed. De-escalation without a goal related to de-escalation gets us little to nothing. Are we still interested in containing the Quds force? Do we care about their operations in Iraq, in Syria, elsewhere? Are we acting to enable allies (i.e., Israel, Saudi Arabia)? Our messaging on this is inconsistent, even to those of us inside the defense fold.

So, in a messaging game, we’ve given an adversary a messaging advantage. We did not give it to them for free—we required the trade, in blood, of one of their most active commanders, and dealt them a setback. I would not expect them to be comfortable with that, and I would anticipate more retaliation through asymmetric actors (such as Hezbollah, or perhaps cyberattacks).

There is an argument to be made that the president is running his own messaging campaign, and it’s domestically targeted. I give a lot of credence to this idea—and need to mention how dangerous (and foolish) it is. The international stage is a bad place to mess around with these concepts, as the consequences involve folks far away from the reality of it.

This message was simple: This was Obama’s fault, nothing happened, I won. None of it makes a lot of sense unless you buy into Trumpism writ large (the weapons fired were older weapons, developed long before the JCPOA unfroze Iranian assets in US banks; it was a demonstration by the enemy, not a decisive blow; and nobody won this outside of the messaging field because there’s nothing to win, and in the international realm, the adversary has seized the advantage).

But terrible calculus for political theater is this administration’s hallmark. I predict that nobody will be celebrating this event (or care much at all) by the time we get to summer, let alone November. The pace of modern politics moves too quickly. Most Americans barely remember the elimination of al-Baghdadi, let alone Trump’s punitive strike on Syria two years ago.

Eventually, we will run across an adversary that will escalate, that will note that whenever it looks like real war is on the line, Trump backs down. That adversary will not hit a bunch of empty buildings. It may be the DPRK, maybe Iran, maybe someone bigger, but for an unpredictable president, Trump is quite predictable about this.

The bigger problem to result from this isn’t Iranian in nature, it’s internal to the US and US policymakers. It is unclear how much closer we are to any of our goals, because it isn’t clear what any of our goals are. This isn’t unpredictability, or poor messaging—it is straight-up incoherence.

We have many micro-goals feeding nothing. Our macro goals are either written down, or ignored, or simply do not exist. One repeated goal, the elusive (or illusive?) “deal,” is, as of writing, an abject failure. There is no indication the Iranians want to negotiate, and the messaging advantage they’ve just been handed will shore up their resistance to such a deal.

I said when Soleimani was executed, and I’ll repeat now: Our best play here is to call this victory and move on, either disentangling ourselves from the region or passing on responsibilities to local powers and allies. If that’s not our larger goal, then I don’t know what we want—a state of perpetually heightened tensions will do nothing but preserve Iran as a vulnerable flashpoint (like the DPRK, the South China Sea, and the Baltics).

Well said. I agree.

PARTISANSHIP AS CAMOUFLAGE

A few more points.

A few weeks ago, Simon Rosenberg wrote an article arguing that Trump had softened his stance on Iran as part of a broader alignment of US policy with Russia’s:

Not only has the United States taken very pro-Putin stances in Russia’s hot wars in Ukraine and Syria, but on a grander scale Trump has helped convey U.S. weakness and Russian strength in region after region across the world — a dangerous development which is going to create enormous challenges for the United States and the West for years to come.

In Syria, he argues, Trump’s hasty and feckless retreat sent a global message about American unreliability. In May, right after speaking to Putin on the phone, Trump abandoned the international effort to rid Venezuela of Maduro, who remains, “essentially under Russia’s protection.” As for Ukraine, Trump’s behavior is infamous.

I’m not really sure that we’ve collectively processed here the gravity of what Trump asked of Zelensky that day—it was essentially a request for him to commit national and political suicide, and made it very very clear that regardless of where the U.S. government stood, Trump himself was with Russia.

Again and again the president has conveyed his sympathy toward Russia in this hot war, including when he ominously turned the August G7 meeting into a discussion about removing the sanctions from Russia for its illegal annexation of Crimea. Rudy Giuliani’s return to Ukraine … should be read as a very public show of Trump’s contempt for Zelensky. It [came] days before the Ukrainian president’s face to face peace talks with Putin that start Monday in Paris, a gathering where the United States is conspicuously absent.

Rosenberg, referring to reports that John Bolton had resigned over what he believed to be Trump’s appeasement of Iran and slavish demeanor toward Putin, speculated that we had we reached the point of crisis because Iran and Russia miscalculated. Given that Trump had spent the past year dramatically re-aligning US foreign policy toward Putin, and given his eagerness to surrender in Syria, perhaps it seemed obvious to Iran that the US could now be pushed out of Iraq, too.

This, he surmises, may be why Iran grew more and more daring. Trump’s “weakness, appeasement, and chaos has invited all this,” he concluded. “The calculation is that Trump won’t or can’t mount a successful war, and the effort to get US out of Iraq will continue in the coming weeks.”

Perhaps. I’m not sure whether the effort will continue in the coming weeks, but I expect it will continue. Iran has a clear strategic goal: evicting the United States from West Asia. I don’t believe it will waver from this.

This is compatible with Russia’s goal, which is similar. Julia Davis always does a good job of rounding up Russian media reactions to world events, and from her synopsis, it sounds as if the Kremlin is delighted by this entire turn of events. Russia enthusiastically denounced the killing of Soleimani as lawless and destabilizing, of course, while barely containing themselves from salivating about its consequences:

Military analysts and state media pundits rejoiced at the perceived humiliation and weakening of the United States on the world stage. Russian state TV programs repeatedly broadcast the photograph of American President Donald Trump with missile-shaped slap marks on his face, originally posted on a Twitter page linked to the Iranian Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

A host of Russian defense analysts opined that this was the way to deal with the Americans, brutes who only understand the language of violence. On one state television show, military analyst Igor Korotchenko berated the American panelist:

You crapped all over yourselves, that’s why the United States needs to shut up! Your time is over!” said Korotchenko. “America is no longer the same. It’s come to nothing. America admitted its own defeat, politically and militarily. Iran—an independent strong country, which is significantly weaker militarily—whipped and slapped you all over the face. Two waves of missile strikes—where are your Patriot [anti-missile] systems? They detected nothing and couldn’t ward off the attacks. You utterly screwed up. America is not the same and the world is different. The year 2020 is breaking all established norms. Not one of your allies relies on you—not in Europe or the Middle East. You're weak and helpless … You’re losing the status of a superpower. Your weapons are bad. Your allies found out that it's senseless to rely on the United States or their weapons systems. Your Patriot systems are ineffective, nothing more than a bluff. … The year 2020 opens up new opportunities, it will be the time of new alliances—and the place of the United States won’t be in the lead, but somewhere off to the side ... Iran’s missile strikes are not the final stage of the retaliation. You will no longer be able to decide the fate of the world. This is the collapse of the global U.S. domination. The multipolar world is coming into power in 2020. This represents new opportunities for our country. [Davis’s translation.]

Col. [Ret.] Igor Korotchenko is the editor-in-chief of “National Security Magazine,” serves on the Russian Defense Ministry’s public council, and speaks in tune with the Russian defense and security apparatus.

If you want to see the remarkable power of machine translation, try watching this—make sure the subtitles are set to English.

Remember, that’s state-funded Russian television, so it’s reasonable to imagine this is what Putin has concluded, too.

Korotchenko summed things up from Russia’s point of view:

Today, Turkey, Russia and Iran are jointly working in Syria … from where you've been asked to get out. Tomorrow, you’ll get out of Iraq and then you’ll get out of everywhere else, because no one else places their hopes in you any longer. Other countries will be seeking support and alliance with Russia and buying Russian weapons … Russian political and military leadership is smarter and more successful than the Americans. That is the problem of the United States—the incompetence of their leaders. We are competent and that’s why we’re winning … We’re back in the Middle East, we’re again in the league of great nations. If the United States has a problem with that, criticize your own leadership that keeps on losing to us.”

It does seem a widespread perception in Russia that the winner of this conflict is Moscow. Sergei Strokan writes, for example, in Kommersant,

The confrontation between the United States and Iran—Russia’s main competitors in the struggle for influence in Syria and the wider Middle East—fetters their hands, distracting them from solving other tasks. It is impossible to fight with equal effectiveness on several fronts. Weakening each other, Washington and Tehran noticeably expand the Middle East corridor of opportunities for Moscow, which has managed to stay above the fray.

It gets interesting here. Responding to Rosenberg, Shadi Hamid wrote something that should be a matter a matter of consensus. That it isn’t is revealing.

This is correct. But the comment was controversial. Fights immediately broke out on Twitter over which president had ceded more to Russia and Iran.

I took the bait:

(I meant to write ‘82.)

Arun actually knows better. The answer to the question, “Under which president did Iran expand most significantly” is “Obama,” and of course this is true, and there is only one right answer. The point of Obama’s policy was to cede influence to Iran and Russia—as Arun implicitly concedes by saying, “And so what?” The alternative, in Obama’s mind, and he was probably correct, was war, or an unacceptably high risk of it.

There is no point in arguing this; if you don’t acknowledge it, it is because you’ve paid no attention at all to events in the Middle East—which is not true, in Arun’s case—or because you’re so given over to partisan passion that you can no longer marshall a sensible argument.

If you want to make the case that Obama’s policy was better, your argument should be that in exchange for handing influence over much of the region to Russia and Iran, the US stayed out of war. You might perhaps add that you don’t see any reason for the region not to be dominated by Russia and Iran, given that our efforts to bring less sanguinary and despotic regimes to power in the region have failed. These would be sensible arguments. I wouldn’t agree with them, but I wouldn’t say, “What planet have you been living on?”

Onye Nkuzi, a Twitter pal from Nigeria, watched this debate, puzzled, then remarked:

Exactly.

Obama was elected to end the war in Iraq. He delivered what was asked of him. Trump was elected to keep us out of wars in the Middle East while making bellicose threats, disgracing us on Twitter, and exhibiting poor impulse control. He’s delivering what was asked of him. If Americans don’t like the consequences, they should stop asking their presidents to get them out of the Middle East. But if we pretend this isn’t what we asked for, or that we could never have guessed who would fill the vacuum, we make ourselves the victims of our self-deception. We render ourselves unable to discuss reality—and unless we do, we cannot decide, like adults, what we do and do not want.

IRAN AND OBAMA

Here you go, Arun.

What of the argument that Obama bolstered the regime by relieving sanctions, whereas Trump has pressured it by applying them? They are both weak. They’re arguments about domestic politics, not Iran.

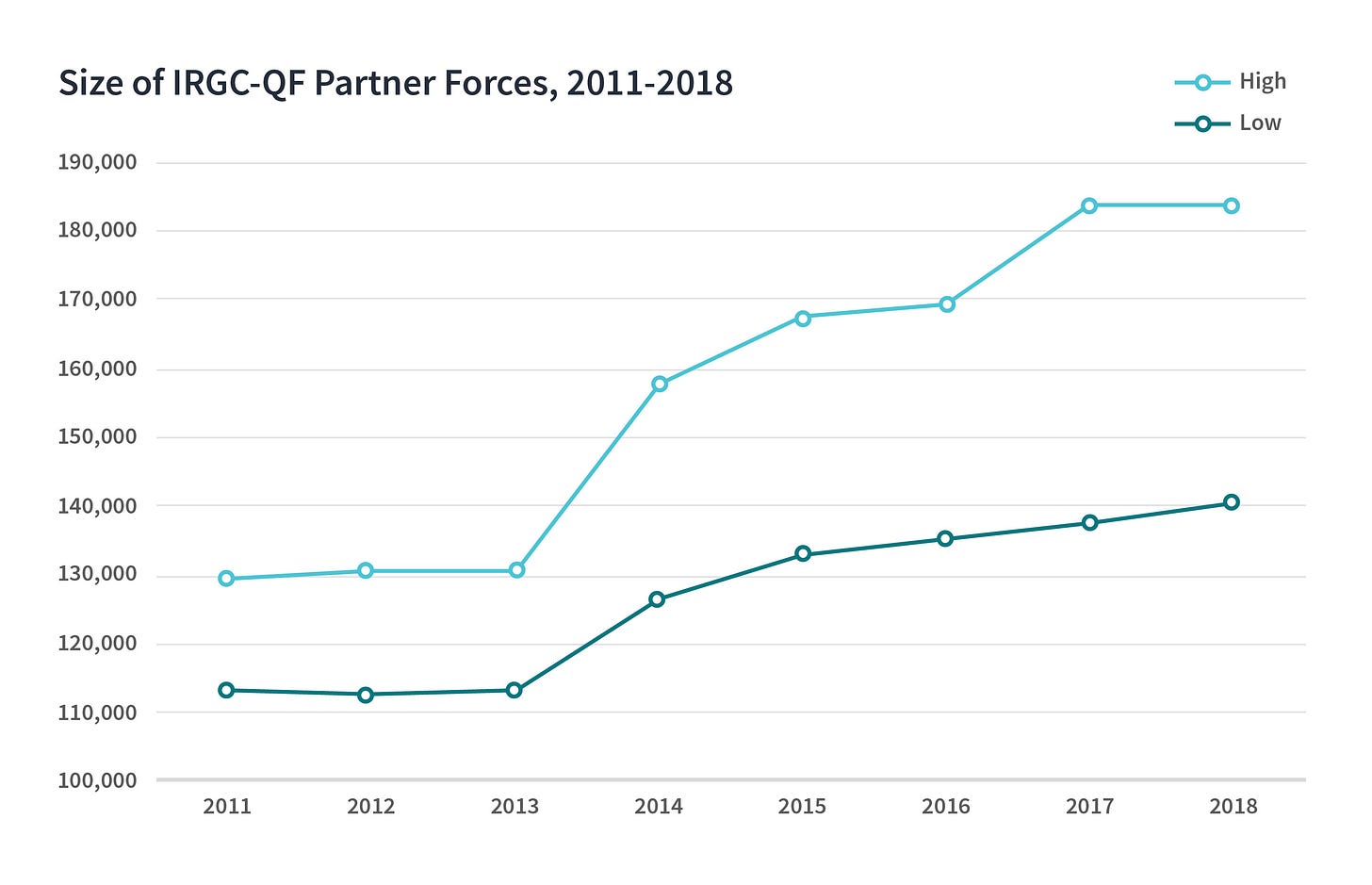

Neither the JCPOA nor Trump’s sanctions halted Iranian expansion. Under Obama and Trump, the size and capability of Iran’s proxies—foreign forces directed by the IRGC-QF—grew, as did Iran’s ability to move fighters and material from one theater to another.

Neither Obama’s palliation nor Trump’s sanctions diminished Iran’s involvement in the war in Yemen. Neither dissuaded Iran from providing ballistic missiles to the Houthis (which they used against the Saudis).

Now, you might say that you don’t care, so long as it kept the US out of these conflicts—which it didn’t, but that’s not the point. You can’t just argue none of this happened.

Neither Obama’s diplomacy nor Trump’s anti-diplomacy diminished Iran’s escalating conflict with Israel in Syria. Neither put a damper on the steady growth of Shia militias in Iraq. Neither diminished the pace of Iran’s targeted assassinations, nor of its cyberattacks. Over both presidencies, Iran’s partners improved their missile and drone capabilities—with the aid of the IRGC-QF, supervised by the departed and unlamented Soleimani.

The war in Syria, primarily, permitted Iran’s expansion. This coincided with Obama’s presidency. By 2014, Lebanese Hezbollah had deployed its fighters to Syria. (Under Obama.) Iran trained, equipped, and funded Shia militias from the entire region to support Assad. (Under Obama.)

Today—despite the sanctions—Iran supports Hezbollah, which it has equipped, under both Obama and Trump, with a massive range of weapons. They may even have given them chemical weapons. Hezbollah has become more, not less, involved in Lebanese politics since the 2018 parliamentary elections. It has increased, not decreased, its influence on the government.

Iran’s influence along the Red Sea grew under both Obama and Trump. In 2016—that is to say, right in between maximum appeasement and maximum pressure—Iran began sending the Houthis anti-tank guided missiles, sea mines, aerial drones, Katyushas, MANPADS, explosives, ballistic missiles, unmanned explosive boats, radar systems, and mining equipment—with which they’ve threatened shipping near the Bab el Mandeb and attacked Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Iran has helped its Shia militias in Iraq to build their own missiles. They’ve built missile factories north of Karbala and east of Baghdad. The sanctions have barely dimmed Iran’s eagerness to proliferate missiles, missile technology, and missile parts, and why would they? The sanctions don’t affect the regime, just the people.

Under Obama—and then Trump—Iran organized and funded more than 100,000 Shia fighters in Syria. Iran (Soleimani, specifically) planned and executed the 2016 operation to retake Aleppo, working closely with Assad and Russia. Under Obama— and then Trump—Iran funded the Ridha Forces, the Companies of the Islamic Resistance in Syria, the Baqir Brigade. They trained thousands of fighters and provided them with advanced weapons, sophisticated cyber capabilities, and a massive number of recruits.

Iran—under Obama—organized 15,000 Afghan militants and deployed them to Aleppo, Daraa, Damascus, Hama, Homs, Latakia, Palmyra, and Dayr az Zawr. They did the same thing with their Pakistani brigade and their Bahraini fighters. (They also tried to overthrow the Bahraini government. Several times.) Meanwhile the grew their operations in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Iran did all of this in a tactical alliance with Russia, and did most of this under Obama. They didn’t do this because of the JCPOA. They did it because the Syrian and Iraqi wars made it possible. To the extent Obama is responsible, it’s because he declined to intervene in Syria. Trump doubled down on that decision. If you deplore one but not the other, partisanship has taken over your frontal lobe.

What of the money Obama returned to Iran or the sanctions Trump has imposed? In the past decade, Iran has spent nearly $140 billion on its military ambitions. The money we returned, about $1.8 billion, was a drop in the bucket—nowhere near enough to fund an expansion like that. Anyone who says it was is innumerate.

Likewise, the sanctions haven’t made much of a difference. Iran has cut its military budget, no doubt in response to the financial hardship we’ve imposed. But the budget was so large to begin with that the cuts barely affect its ability to project power—it can still do a massive amount of damage, if it wishes, and that’s the only metric worth measuring.

By 2016—before Trump’s inauguration—J. Matthew McKinnis testified before the Senate,

The IRI has significantly expanded the size and complexity of its proxy force in the past five years [NB: Under Obama], due primarily to the wars in Syria and Iraq. …

The IRI continues to invest in training and arming its proxies and partners with increasingly advanced equipment, with its most trusted groups receiving the best weaponry. Lebanese Hezbollah has acquired unmanned aerial vehicles and an estimated 100,000 to 150,000 rockets and missiles through Iranian assistance, including advanced air-to-ground and ground-to-sea missiles. The IRI’s Iraqi proxies employed the QFs’ signature improvised explosive device, the explosively formed projectiles against coalition forces in the last decade. Yemen’s al Houthis, in contrast, have received mostly small arms from Hezbollah or the IRGC, although there are indications the movement has gained some Iranian rocket technology.

Perhaps more important than weapons are the tremendous strides the IRGC has made in the past five years advancing their proxies’ deployability, interoperability, and capacity to conduct unconventional warfare. The corps has effectively moved its Iraqi, Afghan, and Pakistani proxies into and out of the Syrian theater as requirements demand. In addition to building the NDF and coordinating with Lebanese Hezbollah, Russian, and Syrian government operations, the IRGC, along with some Artesh special forces units, has also begun rotating cadre of its brigade-level officers to Syria to train and lead the Shia militias in their counterinsurgency campaign. The IRI is in effect turning the axis of resistance into a region-wide resistance army. Recent estimates indicate more than a quarter million personnel are potentially responsive to IRGC direction.

All of this occurred under Obama. These proxy groups are an ideological extension of the Islamic Republic; they proclaim their ultimate allegiance to the Supreme Leader. They’re financially dependent upon the Quds force. They are, obviously, a threat to Israel, Jordan, and the GCC states; if we wish to remain a global power, they’re a threat to us.

But it’s no better under Trump. Despite the sanctions, Iran continues to strengthen and enlarge the whole gamut of Shia militias in Iraq the Badr Organization, Kata’ib Hezbollah (who killed a US contractor, leading to the mess we’re in), and Asaib Ahl al- Haq. They support, fund, and train the Afghan Liwa Fatemiyoun, the Pakistan, Liwa Zainabyoun; they support Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. They’re building routes to the Mediterranean through Iraq’s Kurdish region, the Iraqi city of Sinjar, and northeastern Syria cities like al-Hasakah into Lebanon. They’re building a southern route to Lebanon through al-Walid in Iraq, al-Tanf in Syria, and Damascus.

“These corridors,” notes Center for Strategic and International Studies, “resemble the Royal Road, the ancient land bridge built by Persian King Darius the Great in the fifth century BC.”

This might suggest something about how likely it is that Iran can be deterred by sanctions or diplomacy.

I was going to lay out the details of Russia’s expansion in the region under Obama, but I’ve run out of space. I’ll leave it as an exercise.

WHAT’S THE PAYOFF?

The issue is not Obama versus Trump, Democrats versus Republicans. It is that we wish for things that cannot both be true. We don’t want to be at war, but we don’t want the world to be overrun by hostile and despotic regimes. We don’t want to go to war to prevent Iran from acquiring the Bomb, but we don’t want Iran to acquire the Bomb. We want to scare Iran. But we don’t want to be scared.

We busily project half of our incompatible desires onto the other political party, rather than acknowledging that our own desires are in conflict. Meanwhile, no one mentions that we have no recognizable strategy for anything and haven’t had one since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Astute psychotherapists know that when a patient keeps doing something self-destructive, something he claims he doesn’t wish to do, it’s useful to ask, “What’s the payoff?” What do you gain from failing at work? What do you gain from staying with your abusive husband?

The latest edition of the psychiatric manual on diagnosis includes, for the first time, a tentative category of “self-defeating personality disorder.” Researchers will discuss the personality pattern at today’s session of the annual convention the American Psychological Association.

They, and others interviewed, described the intricate gamesmanship that involves accepting blame or a loss of one sort in order to avoid the risk of a setback that seems even more threatening.

For instance, someone who says he missed an important interview because he lost track of time, may be more able to accept the appearance of temporary incompetence than the risk of failing in the interview. And he can maintain the flattering illusion that success in the interview would have been probable, but for this small failing.

Perhaps whole countries are subject to similar dynamics. Might this be a useful way to understand our political polarization? It is, obviously, dysfunctional. We clam not to wish for it or like it. We say we’re baffled by it.

What’s the payoff?

If we weren’t so deranged with partisanship, we might be obliged to speak seriously about our conflicted foreign policy aspirations and the way they manifest themselves in incoherent foreign policy. We might have to acknowledge the failings of candidates and policies we supported, which would be profoundly ego-dystonic and demoralizing. We might have to face a truth we don’t want to confront: Some problems have no good solutions.

Vitriolic partisanship serves a useful sociological, political, and emotional purpose. It prevents us from having to be unpleasantly honest with ourselves. If we weren’t all so busy denouncing Trump or Obama—and each other—we might have to ask ourselves whether the goals of “ending endless wars,” living in a free country, and preventing Russia, or Iran, or ISIS from rolling over the civilized world are compatible.

Perhaps they are not. Perhaps the only way to ensure there is no nuclear Iran—or Russian tanks rolling through the Suwalki Gap, foreign interference in our elections, unpleasant videos of ISIS beheadings, refugee crises, Chinese concentration camps, and blood-hungry Mexican cartels—is to pay a very high price, a price in money and opportunity costs and the blood of our loved ones, a price that comes with no certainty at all that we won’t miscalculate our way into a nuclear exchange or create more terrorists rather than fewer.

Perhaps the price is the anxiety we’ve all felt in the past week, wondering if we’re about to stumble our way into a catastrophic war, or whether our flight will be next to tumble out of the sky.

Perhaps there need be no price. Perhaps there’s a better way. But what is it, and why haven’t we found it so far?

Half a million dead Syrians, the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War, a divided Europe, and a Russia that clearly feared no one, certainly not us, when it invaded Ukraine—and then casually threw our elections and laughed about it. Why didn’t Obama’s diplomacy work?

Why haven’t Trump’s threats and bluster worked?

Who wants to think about that?

It’s much easier to think about how much we hate Trump. Or Obama. Or white supremacists. Or Antifa. Or really, anything but that, because that;’s not pretty to think about.

Bush in 2000, Obama, and Trump all campaigned on the promise of avoiding foreign entanglements. No more nation-building abroad. Just some nation-building at home—it’s going to be infrastructure week, for sure, one of these days. No more stupid wars. No more wasted money. No more mangled veterans.

They all failed.

Each president now comes to mind resolved to be the antidote to his predecessor. Obama would be the antidote to Bush. Trump would be the antidote to Obama. Each president finds himself reacting not to the reality of the world—which often stays much the same, even as our presidents change—but to the phantasm of the man before him. Our foreign policy, meanwhile, becomes increasingly detached from the foreign. It has become an extension of our domestic policy debates.

Partisanship is harming our ability to think straight about what price we’re willing to pay for peace—and perhaps that’s the point of it. It’s clouding our ability to formulate and execute any reasonable strategy, under the proper democratic supervision of We, the People—or forthrightly to discuss the risks, costs, and payoffs of the strategies we do pursue. We’d all rather pretend that if only we had the right president, and if only the other half of the country (our shadow selves) would march into the sea, we could square all these circles. We would live in a peaceful world where no one dies and we didn’t have to pay taxes.

That’s the payoff. The cost, of course, is our own infantilization—and even that’s assuming our luck holds out.

America, Fuck yeah.

Let’s conclude on an optimistic note:

We can afford to make a hell of a lot of mistakes.

From the Eric Hines school of theology:

<i>it seems like a <i>genuine miracle</i> and a direct response to an unuttered prayer.</i>

Prayers may go unspoken aloud, but God knows what's in our hearts; no prayer is unuttered. So, boys and girls, be careful of what you wish--you might get it.

And a comment on your larger thesis:

<i>At the end of the First Battle of the Marne, it was too soon to tell who would emerge victorious from the Great War, but not too soon to say that no one’s initial objectives— be they to chasten Germany in a jolly war that would be over before Christmas, or to ensure security for the German Reich....</i>

It's not only time that interferes with our ability to say what an outcome will be. Also interfering with the accuracy of those predictions is the falseness of the going-in proposition(s)--here, for instance, that it would be a quick (and fun!--geez) war, or that any war makes any nation secure for all time--rather than just driving the wolves from the door, or even the local part of the forest for a time.

Eric Hines