We Hate Each Other, but Why?

Let’s consider our hyper partisanship. Survey after survey finds that partisan antipathy has skyrocketed in the past quarter century. You know this. You don’t need a survey to tell you this. But let’s skim through the numbers anyway.

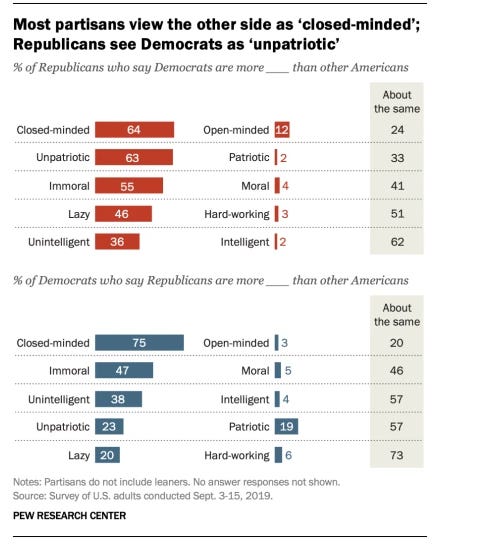

In 2016, 70 percent of Democrats reported that they held Republicans to be closed-minded. More than 50 percent of Republicans believed the same about Democrats. Nearly half of Republicans viewed Democrats as immoral and lazy. Nearly half—among both parties—believed members of the other party were dishonest. Among both parties, a bit less than half—44 percent—reported that they “almost never” agree with the other party about anything. More than half—about 55 percent—reported themselves “afraid” of the opposite party.

Unsurprisingly, this antipathy has deepened since 2016, particularly on the GOP side. Republicans are now more likely than Democrats to ascribe multiple negative characteristics to partisans of the other camp, with 70 percent assigning two or more negative qualities to Democrats. Democrats became more hostile, too, with 58 percent associating Republicans with two or more negative traits. Democrats have now caught up to Republicans in believing their opposite numbers are immoral.

Disproportionate Animosity

This mutual antipathy is profoundly, even wildly, disproportionate to real ideological differences or disagreements about policy. Americans are in fact in broad agreement—to the point of homogeneity—about most significant political issues. A few statistics illustrate the point:

96 percent blame “money in politics” for our political dysfunction;

92 percent say it is “very" or “somewhat" important for the US to be energy independent;

90 percent think a background check should be required for every firearm purchase;

89 percent are concerned about the influence of foreign money on American political campaigns;

87 percent say it’s critical to preserve Social Security, even if it means raising taxes;

85 percent are against deporting undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children;

85 percent believe our campaign finance system needs fundamental change;

84 percent oppose civil asset forfeiture;

82 percent think economic inequality is a big problem;

80 percent disapprove of sanctuary cities;

78 percent support more regulation of the financial industry;

78 percent favor establishing a national fund that offers all workers 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave;

76 percent believe the wealthiest Americans should pay higher taxes;

76 percent of voters are “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about climate change;

73 percent have an unfavorable opinion of Citizens United;

69 percent favor signing international agreements to limit greenhouse gas emissions;

61 percent believe the US should strive to be the world’s largest military power;

Overwhelming majorities say that Trump’s behavior makes them concerned (76 percent), confused (70 percent), embarrassed (69 percent) and exhausted (67 percent).

81 percent report themselves concerned about our growing partisanship.

Pew published this table with the title, “Partisans far apart on the importance of many issues.”

It would be just as accurate to say, “Not much partisan difference on most issues,” wouldn’t it?

The most significant partisan disagreements fall under the categories, “Environment” and “Climate Change,” and to a lesser extent, “Military” and “Terrorism.” But there is nothing in this table that suggests massive, irreconcilable differences. Rational people could look at this and say, “What good news! It looks as if Americans are in broad agreement about everything significant. All we need is for the GOP to indulge Democrats on environmental issues; Democrats, in turn, should agree to prioritize the military. Then we’d have no real disagreements at all.”

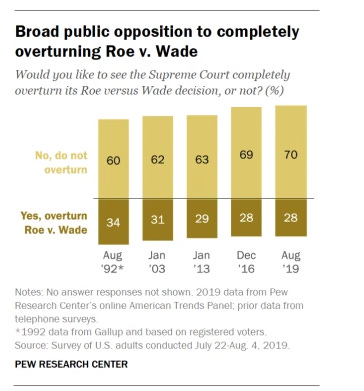

On many of the most controversial issues, Americans are growing closer to each other, not further. Most Americans—70 percent—believe homosexuality should be accepted, not discouraged. (The older you are, the more apt you are to be horrified by gay marriage.) Support for Roe v. Wade is growing, even as support for unlimited abortion is declining.

Even so, hatred of the opposite party is skyrocketing. In 1960, fewer than five percent of Americans claimed they would be unhappy if their child married someone of the opposing party. By 2019, a third of Democrats and half of Republicans opposed inter-party marriage.

We are now more divided by party than by race. Nor is party a proxy for race: It’s an identity in itself. You are more likely to face discrimination in the workplace—or to be rejected in love—because of your political party than because of your race, gender, age, ethnicity, educational attainment, religious affiliation, personality, or physical appearance. That’s some strong juju, no?

The stated preference for same-party marriage is but the tip of an evidentiary iceberg concerning the growing relevance of partisan cues for interpersonal relations. Actual marriage across party lines is rare; in a 2009 survey of married couples, only 9% consisted of Democrat-Republican pairs (Rosenfeld, Reuben, and Falcon 2011; also see Stoker and Jennings 1995). Moreover, marital selection based on partisanship exceeds selection based on physical (e.g., body shape) or personality attributes (Alford et al. 2011). Recent data from online dating sites are especially revealing. Even though single men and women seeking companionship online behave strategically and exclude political interests from their personal profiles (Klofstad, McDermott, and Hatemi 2012), partisan agreement nevertheless predicts reciprocal communication between men and women seeking potential dates (Huber and Malhotra 2012). As the authors of one intermarriage study put it, “the timeless character of political divisiveness may emanate not just from the machinations of elites, but also from the nuances of courtship” (Alford et al. 2011, 378)

The issues that divide us aren’t commensurate with this kind of loathing—particularly because both parties are comprised, overwhelmingly, of white, middle class, heterosexual, non-evangelical Christians.

Members of both parties are, moreover, completely delusional about the demographic composition of the other party. On average, Democrats believe 38.2 percent of Republicans earn more than $250,000 per annum (as opposed to 2.2 percent). Republicans overestimate the number of gay Democrats by 500 percent.

And both sides view each other as a serious threat to the Republic.

A Global Phenomenon

Why are we so persuaded that our divisions are irreconcilable and our partisan counterparts dishonest, lazy, low, and immoral?

The two most commonly-advanced theories are geographic. Many believe this devolves from a great geographic sort: Southern conservatives deserted the Democrats; Republicans no longer have a foothold among Northern liberals. The second theory is that the number of congressional districts with truly competitive elections is diminishing. The meaningful electoral competition now happens in party primaries, which discourages candidates from running as centrists and forces them toward the extremes.

Both of these ideas are reasonably plausible, but neither suffice, on closer inspection. Why? Because any theory we advance to account for this state of affairs (including the theory that the opposite party is just rotten) has to be capacious enough to account for this peculiar fact: Debilitating partisanship is a global phenomenon, not a local one. This suggests our intuitively plausible hypotheses are at best incomplete, and probably flat-out wrong.

Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue, for example, have undertaken a comparative analysis of political polarization in countries as varied—socially, historically, economically, ethnically—as Brazil, India, Kenya, Poland, and Turkey. All of these very different countries have been torn asunder in a remarkably similar process of polarization.

It’s impossible to imagine this is a coincidence. Something—perhaps even a single thing—is causing this, and it is something particular to our era.

But it’s hard to imagine what it might be. These countries are more dissimilar than alike: They are at different stages of economic development; they have entirely different ethnic, religious, class, and social cleavages; their media environments are not alike; the degree of internet penetration and usage is not the same; the most pressing political problems facing their electorates are not the same. So how have we all wound up at the same place?

Carothers and O’Donohue conclude that the decisive common factor is a polarizing leader—a figure they term the political entrepreneur. Modi, Kaczyński, Erdoğan, Trump, and their analogues, they argue,

have relentlessly inflamed basic divisions and entrenched them throughout society (often with resounding electoral success). They’ve aggravated tensions not only by demonizing opponents and curtailing democratic processes but also by pushing for radical changes—like a total ban on abortion in Poland.

This is unquestionably true, but it begs the question. It has no explanatory power. The real question is why these dissimilar countries have all become susceptible, at the same time, to the appeal of these personalities. Something, clearly, was wrong to begin with—wrong in a similar way. But what?

What do all of these countries have in common? Could the rise of social media be to blame?

Amplifying the effect of these divisive figures is the technologically fueled disruption of the media industry, especially the rise of social media. Opposition leaders often fan the flames as well by responding with antidemocratic and confrontational tactics of their own. In Turkey, for instance, the head of the main opposition party stoked tensions by calling on the military to oppose Erdoğan’s potential bid for the presidency in 2007.

It’s a tempting theory, but again, it doesn’t fit the facts: Political polarization in the United States, for example, is greatest among those who use the least social media. How would the rise of social media explain the polarization of Bangladesh, where only 18 percent of the population have ever used social media?

But what else could it be? No other theory seems to fit the facts, either.

Many other drivers of polarization struck us as surprising, even counterintuitive. You might expect, for instance, that a growing economy would ease polarization. Yet we found that in some places, such as India, it actually made things worse. Indeed, the growth of India’s middle class has led to rising support for polarizing Hindu nationalist narratives.

We also found that patronage and corruption—two decidedly anti-democratic practices—can temporarily reduce polarization by helping politicians build very big tents. In the long term, however, the political rot that this causes frequently leaves voters disgusted with the traditional parties and fuels the rise of divisive populist figures, like Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

A Harbinger of Democratic Breakdown

Whatever the cause, it’s deadly dangerous, and a harbinger of total democratic breakdown.

Polarization leads to legislative gridlock and dysfunction, which in turn erodes public trust in democratic governance and institutions.

When polarization grows acute, politicians and their supporters begin to view their rivals as illegitimate, even an existential threat.

Then democratic norms weaken. Politicians become willing to break the rules—and to cooperate with anti-democratic extremists and tolerate violence—to keep their rivals from power.

This process destroyed democracies in Germany and Spain in the 1930s. No one who lived, as I did, though Erdoğan’s rise and consolidation of power can be sanguine about seeing the same processes at work in the United States. Everything I see in Trump is familiar. (Please don’t send me irate emails telling me I’m suffering from Trump Derangement Syndrome. I was told I was suffering from Erdoğan Derangement Syndrome, too. I wasn’t. If you think I’m mistaken about Trump, respond to my arguments, not to my state of mind.)

I received this e-mail the other day from a friend who wishes to remain anonymous. It illustrates all of these processes at work:

One of the major narrative problems with the impeachment is its positioning as a solemn defense of the Constitution, and a curbing of unbounded governmental power—by people who ordinarily loathe the Constitution and love unbounded governmental power. One minute the Constitution is a slaveholder’s document and the Supreme Court is overthrowing millennia of human institutions at the whim of Anthony Kennedy’s feelings; and the next minute the Constitution is Narya the Ring, Galdalf’s aid against Sauron, and the squalid excesses of forpol / natsec skulduggery are existential threats.

Take the thing on its own terms, plead the impeachment partisans, and would that we could. It was possible in 1973. It was also possible in 1998, though they wouldn’t do it then. It is not possible now. We know too much and they have done too much. A defense of liberty and the rectitude of process are fine things and worth defending, but those values do not demand our credulity when the enemies of both appeal to them.

Say they’re right and this is what the President deserves: this and removal too. Accept it for the sake of argument. It doesn’t change what the rest of us understand, because we have known them for so long, which is that their real target isn’t him — it’s us.

It is? He’s not my real target. I think I speak for more than one American in saying that. My real target is Trump: I want a scofflaw, polarizing president who thinks rules are just for the little people out of office. I want the power of the presidency in the hands of a man who respects it, and by extension me.

What makes a man as intelligent and good-hearted as my friend persuaded that my real “target” is “him?”

How can I persuade him that it isn’t—that we both want the same things?

Ideas?