It’s war. Or it might be.

Ukraine and Russia are heading to the point where the brakes come off and no one is in control.

By John Oxley and the Cosmopolitan Globalists

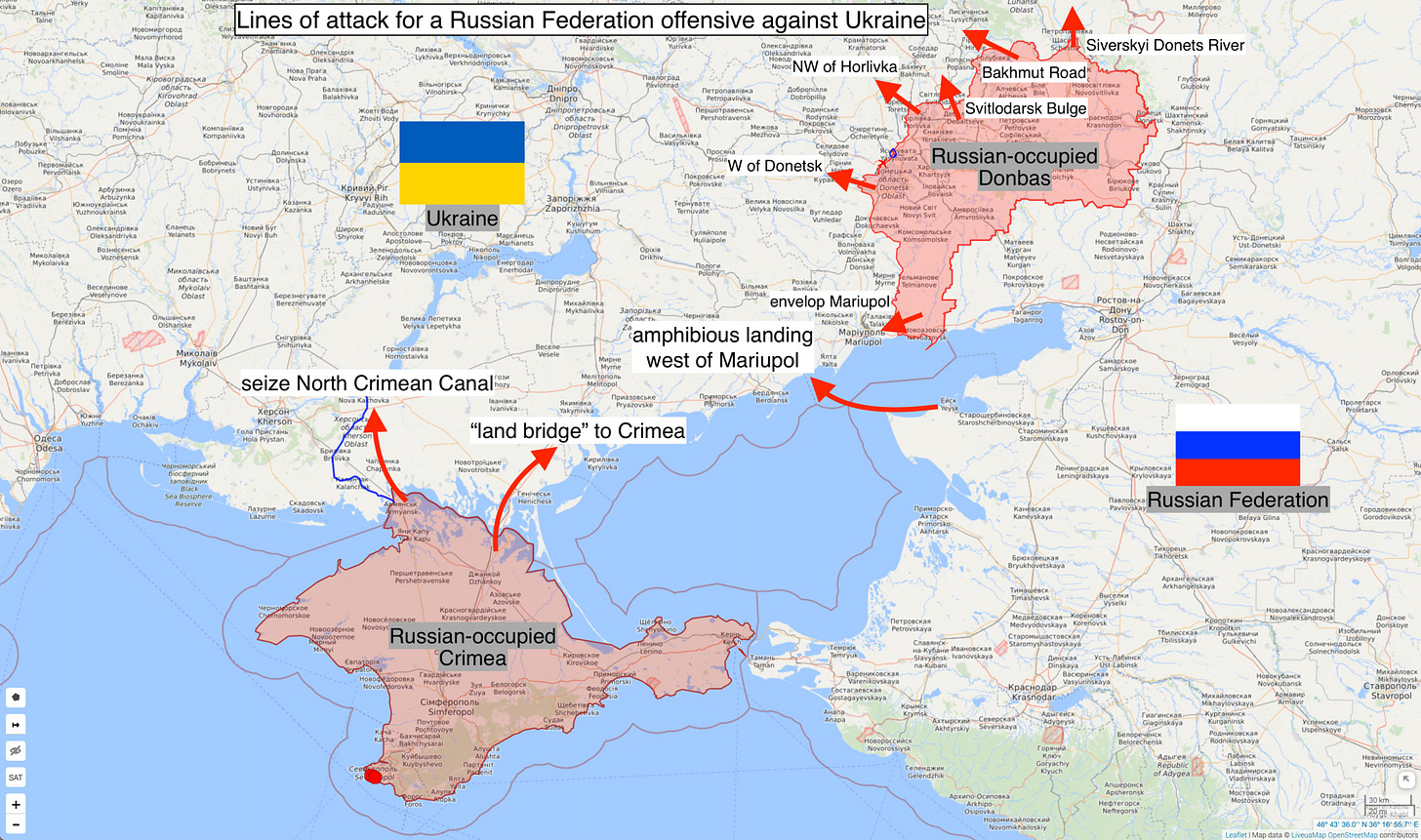

@Liveuamap annotated by Michael MacKay: Potential lines of attack for a Russian offensive against Ukraine. “Putin will attempt to exploit a breakthrough anywhere he can get it.”

Fighting between the Ukrainian army and Russia’s pet separatists in the East has intensified. Russian tanks and guns are moving to reinforce Crimea. This footage purports to show long lines of tanks and artillery en route to the peninsula:

The video is either a fake or those are Russian tanks pouring over the Kerch Strait Bridge. It couldn’t be anywhere else. The railings are distinctive. Russia began building the bridge immediately after invading Crimea (to link it to the motherland, literally and figuratively). It’s the longest bridge Russia ever built and the longest in Europe.

NATO just held an urgent meeting in which allies “shared concerns about Russia’s recent large-scale military activities” in eastern Ukraine and the Black Sea, so we’d bet on “not fake.” EUCOM, too, has raised its watch level from “possible crisis” to “potential imminent crisis” (the highest level). Oddly, this doesn’t seem to be headline news in the United States.

Since 2014, Russia and Russian-backed forces have occupied parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula on the Black Sea. The conflict has claimed some 14,000 lives. Fighting on the Donetsk border has recently increased; four Ukrainian soldiers were killed last week. Putin has meanwhile been flashing a cold smirk and insisting the separatists have nothing to do with him.

The Ukrainian government has reaffirmed its position that Crimea should be restored to its control, by force if necessary, and expressed its determination to join NATO. Russia in turn accuses Ukraine of violating the 2014 Minsk Protocol, drawn-up by the Trilateral Contact Group and signed by representatives from Ukraine, Russia, and the OSCE. The deal brought major hostilities to an end but resolved nothing.

A spokesman for EU High Representative Josep Borrell has noted that Russia has “launched yet another conscription campaign in the illegally-annexed” Crimea and Sevastopol, drafting residents into its armed forces, which is yet another violation of international law.

It seems implausible that Russia would roll west. Crimea is a poor point from which to launch a full-on invasion of Ukraine. Breaking out from a peninsula is strategically unwise, and it would completely undermine their official line on the conflict. The party line is that Crimea is a natural part of Russia—and was liberated by Russian troops—whereas the conflicts in Donetsk and Luhansk are part of a Ukrainian civil war in which Russia is uninvolved. (It is an unfortunate coincidence that the forces fighting the Ukrainian military want more Russian influence in Ukraine, carry Russian weapons, and receive Russian medals.)

Russia is probably hoping to enhance its position by making the peaceful reintegration of Crimea into Ukraine impossible. By packing the peninsula with military hardware, they’re further assimilating it. Laws have recently been passed allowing Crimeans to vote in Russian elections. Foreigners—that is to say, Ukrainians—have been banned from owning property in the region.

Ukraine has tried, in turn, to render Crimea ungovernable. Since the annexation, they’ve blocked crucial canals to keep water from flowing into the peninsula. After seven years of this, the reservoirs are almost dry; farmers and citizens are suffering from drought. Without water and agriculture, Crimea becomes expensive to maintain, needing more and more subsidies from the rest of Russia.

The region has also been ravaged by Coronavirus.

A battle to seize the canals is possible. Russia has carried out war games on this theme. But it’s more likely, given a hardening US line, that Putin is seeking to solidify his position ahead of peace talks.

President Trump’s only interest in Ukraine was using it to manufacture investigations into Hunter Biden. But the United States now has a renewed interest in resolving the crisis. Institutional memory has kicked in: Americans seem to remember that it is their longstanding policy to support, not blackmail, the brutalized former Soviet satellite states. So when peace talks come, Crimea’s status is apt to be determined by the outcome of this battle of attrition and Russification. The injection of troops is probably part of this gambit.

The choice between war and peace, however, may not be Putin’s to make. Russia has already discovered the problem with proxy wars: Things get out of your control. In the first summer of the war, Moscow’s proxies accidentally downed Malaysia Airlines flight MH17, killing every soul on board. Troops without formal command or close supervision—but equipped with heavy weaponry—have the potential to turn Ukraine into an international conflagration.

The Crimean occupation is a more clear-cut conflict. The frontline in the east runs through towns and villages. Incursions and escalations are frequent. Dozens of ceasefires have begun and ended since the signing of the Minsk Protocol. The conflict could easily reignite, since neither party is particularly committed to peace.

Moscow is determined to hold on to its possessions and destabilize its neighbor. Parliamentary elections are ahead. The Kremlin must look tough. Ukraine is determined to protect its integrity and align itself with the West. Zelensky, a former comedian, was elected on the pledge he would get Crimea back. Billboards on every street in Kyiv say, “Крим - це Україна” (Crimea is Ukraine). In neither country do the domestic politics align with peace.

The question is: How big will this get? Ukraine is not yet part of NATO, so the allies are under no formal duty to intervene. But the agreements that brought an end to the Cold War—and persuaded Ukraine to surrender thousands of nuclear weapons—were predicated on promises to guarantee Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Since the 2014 revolution, the Ukrainian government has done what it can to be close to the West.

Since 2014, hearts have hardened toward Russia among the United States and her allies. Russia’s interference in Western elections, along with its liberal use of Novichok at home and abroad, have caused many to conclude it ought not keep expanding.

Columns of tanks heading toward a disputed territory are rarely a good thing. When the combatants, chain of command, and objectives are murky, the risks are heightened along with the ramifications. The Pentagon is on high alert. The Western media is snoozing right through it. But this really does have the potential to be an old-fashioned, Cold War-style face-off. With itchy-fingered irregulars at the most finely balanced point, to boot.

We thought you should know.

John Oxley lives in London.

The fact that Russia's ally against Ukraine is a separatist movement in eastern Ukraine is probably the key element of instability in the strategic equation. That movement may be dependent on Russian support but on the other hand it has available to it the potent argument that a weak ally can deploy against its strong partner: If you don't support us, we may collapse. Thus in a certain sense, Putin may be said to have taken a wolf by the ears and dare not loosen his grip. And I have no doubt that the separatists see full-blown war between Russia and Ukraine as the best and fastest way to make good their bid for autonomy leading to fusion with Russia.

I've always wanted to spend a summer in Ukraine just figuring out what, exactly, is going on in that country.