By Thomas M. Gregg

See here for an interactive military situation map of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

V. Putin seems to be getting more and more desperate these days. The latest war news, an abortive drone attack on the Kremlin supposedly launched by the Ukrainians with the objective of killing the Russian despot, bears the earmarks of a false-flag operation. Probably it was staged by the Russians themselves, to make Ukraine look irresponsible and dangerous, thus scaring off the US and NATO. And once again, the Russian government has raised the threat of nuclear retaliation—a threat that decreases in credibility every time it’s repeated.

If the Kremlin attack was staged for effect by the Russians themselves, one can see why. The Russian Army’s winter-spring Donbas offensive has fizzled out with nothing much to show for it, and the disputed city of Bakhmut remains mostly under Ukrainian control. The crude tactics employed by the Russians—essentially massed artillery-infantry attacks—cost them dear while gaining very little ground. If, as seems likely, the offensive’s objective was to preempt the impending Ukrainian spring counteroffensive and push back its start line, it was a dismal failure.

The tactics employed in the offensive make it appear that the Russian Army has lost what ability it had to fight a mobile offensive battle in the style of World War Two. After a bad start in that conflict, the Red Army perfected a technique that minimized its own disadvantages while maximizing its one great advantage over the German enemy: numerical superiority.

In the latter part of the Nazi-Soviet war (1943-45), a Red Army offensive opened with a massive, centrally directed artillery bombardment. Then the unmotorized rifle (infantry) divisions, which constituted the bulk of the army, attacked with the mission of breaking into the enemy’s defenses. This accomplished, the mobile forces—tank corps, mechanized corps, cavalry corps—exploited the breach, driving forward to seize key terrain in the enemy’s rear areas. A successful offensive operation in the Soviet style carried the front forward fifty or seventy-five miles. At that point, the mobile formations would dig in and prepare to repel the inevitable German counterattacks.

Since manpower was plentiful while technical expertise and trained manpower were in short supply, the Red Army allocated the latter to the artillery, which was concentrated in large formations, and the mobile forces. The rifle divisions received lower-quality manpower, for, instance men hastily conscripted in newly occupied territory and given minimal training. They had very little artillery, and it was mostly employed for direct fire on targets visible to the gun crews. The result was a two-tier army, with the rifle divisions serving as cannon fodder, sacrificing themselves to open the way for the armored striking force. It was a costly technique in terms of human life, but that was of little concern to Stalin and company as long as it worked, which it did.

There were two reasons why it worked. First, the Stalin regime employed the most stringent cohesion and outright terror to enforce discipline. Second, given the German invaders’ savage and barbaric conduct, the regime could credibly appeal to the Russian people’s primitive patriotism.

In the present war, Russia finds itself saddled with a similar military problem. Its armed forces, though numerically superior to the enemy, are significantly less efficient. As the Soviet example shows, there are ways around this difficulty—but while the Stalin regime had the will and the means to employ them, the Putin regime does not. Whatever else may be said of the Soviet Union during its war with Nazi Germany, it demonstrated a ruthless efficiency. In its war with Ukraine, Putin’s Russia has certainly demonstrated an oafish brutality, but neither ruthlessness nor efficiency. If it cannot yet be said that Russia has lost the war, it’s now obvious that Russia cannot win it.

The Russo-Ukrainian War has therefore come to a moment of balance, hinging on the outcome of the impending Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Thus far the Ukrainians have stopped the Russians dead in their tracks north of Kyiv, contained the Russians elsewhere, recaptured a good deal of territory, and degraded the battle capacity of the Russian Army. The situation is—very roughly—what it was in early 1943 in the aftermath of Stalingrad. The Russians are on the back foot but not yet defeated. The Ukrainians have seized that most precious military commodity, the initiative. How far can they exploit it? That is the question.

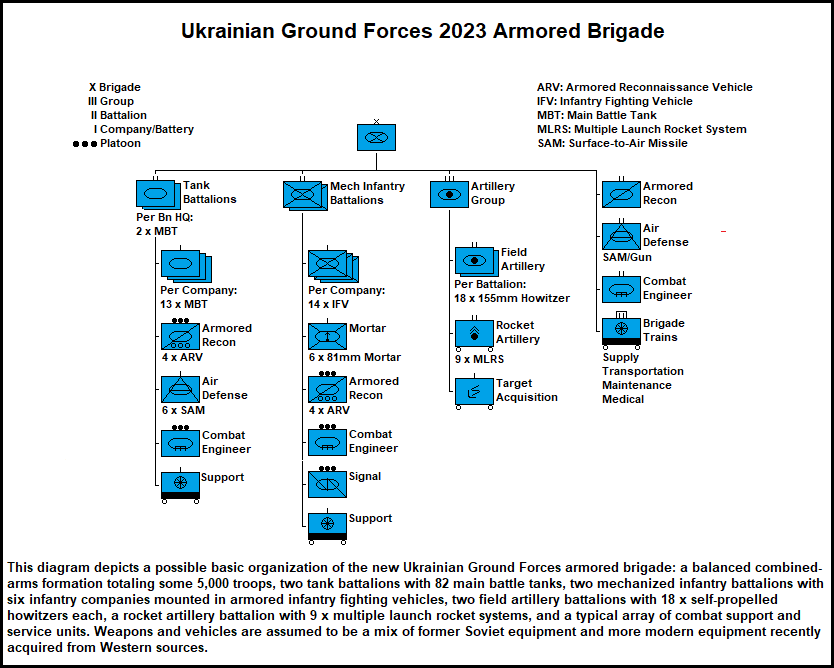

News reports suggest that the Ukrainian counteroffensive will be spearheaded by nine newly formed armored brigades. In fact, these were probably formed by refitting and reorganizing existing units. At the beginning of the war, the Ukrainian Ground Forces had two types of armored formations: tank brigades and mechanized brigades. The former type was armor heavy, with three or four tank battalions (probably with 35-45 tanks each) and one mechanized infantry battalion (mounted in armored infantry fighting vehicles; e.g., the BMP-2). The latter type had three mechanized infantry battalions, one motorized infantry battalion (truck mounted) and one tank battalion. Both types also had a two-or three-battalion artillery group, an air defense battalion, and the usual service and support units.

As their name suggests, the new armored brigades are probably balanced formations, perhaps with two tank battalions and two mechanized infantry battalions. The brigades are said to be trained in combined arms tactics, and such an organization would enable them to form the requisite mission-oriented battle groups by cross-attaching sub-units. For instance, an armor-heavy battle group could be formed by attaching a mechanized infantry company to a tank battalion. It’s also possible that the battalions themselves are organized like the US Army’s combined arms battalions, with organic tank and mech infantry companies.

In recent months the Ukrainians have received some 250 tanks (mostly Leopard 1 and Leopard 2 models) and 1,500 other armored vehicles from various European countries, and these have no doubt been used to equip the new armored brigades.

The accompanying diagram represents my own best guess as to the brigades’ structure: generally similar to the US Army’s Armored Brigade Combat Team (ABCT). However, the Ukrainian brigades may be smaller, with fewer tanks and less artillery.

Where along the front this striking force will be committed remains an open question. It seems reasonable to think that the Ukrainian blow will fall at a place that would confront the Russians with an immediate crisis. One possibility is the Kherson sector, where a relatively short advance would bring the Ukrainians to the Crimean approaches, possibly compelling the Russians to redeploy forces from other areas and facilitating Ukrainian advances elsewhere. (See the interactive map.)

The Ukrainian counteroffensive may be expected to begin sometime in June. It will, however, be preceded by “shaping operations”: short- and long-range ground and air reconnaissance, small-scale probing attacks, guerilla operations behind Russian lines, etc. These operations, which are probably going on now, will be conducted all along the front line to create uncertainty on the Russian side about the sector in which the main blow will be delivered.

Tactically, the immediate objective of the attack will be to rupture the enemy front, ejecting the Russians from their fixed defenses and forcing them to fight the kind of mobile battle for which they’re poorly prepared. If the Ukrainians succeed in doing this, they may be able to score a decisive victory. If not, the war will settle back into a stalemate, with neither side able to force a military decision. It seems mistaken, therefore, to evaluate the coming battle in terms of ground gained and lost: If the Ukrainians can defeat the Russians in a major battle, the territorial gains will come of themselves—and very probably, the war will be over.

Thomas M. Gregg is a retired advertising copywriter and US Army Vietnam veteran with a combined 28 years of active and reserve service. He’s the author of The Double: Twelve Stories and a Poem and A Cold Day in August: Thirteen Tales of Criminality Most Foul. Read more by Thomas M. Gregg at Un-Woke in Indiana, where this essay was first published.

Excellent analysis.

The Russians must be expending enormous resources to figure out where the blow(s) will fall. A lot depends (for both sides) on their success or failure.

The Ukrainian formations will probably resemble the WW2 German Kampfgruppen, which were special purpose formations assembled for a specific purpose. Given the paucity of armor (250 tanks of which the Leopard 1 is at best obsolescent), the key is going to be the attached followup units if a breakthrough is made.

Keeping my fingers crossed.

Speaking as one with little knowledge of military history, tactics or strategy, your argument sounds like good news for Ukraine. I am concerned, however, by the prospect of a long, drawn-out conflict that grinds down Ukrainian manpower and Western resolve (and our resupply capabilities). In addition, while Russian public opinion probably doesn’t count for much in Putin’s calculus, it sounds like Russians would be less willing to give up Crimea than they would the disputed and later, annexed, areas of eastern Ukraine. So, even if Ukraine prevails by force of arms in expelling RUssia from every inch of its territory (including Crimea), that region would fester as the germ of some future effort to get payback by the Russian Bear.