My friend Larry—who was strangely unmoved by my offer to send him ten miracle beauty products—was nonetheless interested in what I had to say about the Doomsday Clock. Or to be precise, he was interested in what he had to say about the Doomsday Clock, and when he saw that I’d written about it, seized his chance. (No, this is not about to become yet another mansplaining complaint. The friend in question is Lawrence Krauss—the theoretical physicist who chaired the Bulletin of the Atomic Society’s Board of Sponsors from 2009 to 2018. He’s entitled to think he has something to say about this.)

He thinks it’s time to get rid of the clock.

I hasten to note that he’s not a dreary vegan feminist fruit-juice drinker or a bearded Irishman in sandals. (It’s kind of worse, actually: He’s one of those proselytizing atheists who’s always banging on about eradicating superstition and religious dogma from our culture even as he’s telling everyone it’s just turtles all the way down. But that’s for another day. Today we’re sticking with Doomsday, which, he and I agree, may well arrive before we resolve the whole turtle thing.)

He sent me his latest piece in The Wall Street Journal about the Clock. Basically, he agrees with me. They’re mixing in too many other threats, and now it’s just confusing people:

“The Bulletin’s Clock is not a gauge to register the ups and downs of the international power struggle,” founding editor Eugene Rabinowitch explained. “It is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age.”

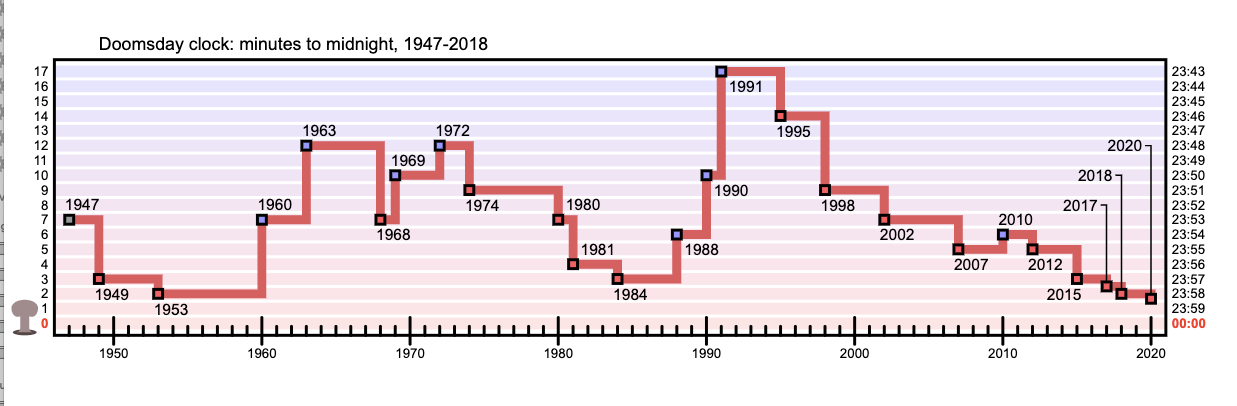

Early on, it often did. It moved forward in 1953, after the U.S. and the Soviet Union developed the hydrogen bomb, or in 1974, when missiles with multiple warheads became a reality. But gradually it broadened focus beyond the physical dangers of nuclear weapons and began taking account of political questions such as arms-control treaties and tensions between India and Pakistan, and, since 2007, of other military threats such as bioterrorism, as well as the global existential dangers of climate change. The 2019 announcement also cited “fake news” and Donald Trump.

He disapproves of the broadened focus. I do, too.

This multiplication of threats has heightened the sense of alarm. The Doomsday Clock time is now much closer to midnight than it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis (seven minutes), when the world really was on the precipice of a nuclear holocaust. At the same time, a clock that has moved back and forth while lingering frighteningly close to midnight for more than 70 years strikes many as crying wolf. At two minutes to midnight, the clock can’t move much further forward, even if threats increase.

More to the point, the threats the clock now purports to measure are different in kind. Nuclear weapons could end human civilization in a day. The generation of greenhouse gases associated with human industrial activity won’t. It is increasingly likely to have devastating impacts, but these will emerge over the long term and be spread unevenly across the globe.

He then points out that the clock isn’t a scientific instrument, but a publicity stunt. (Does that need to be said? Have readers have become so literal-minded and scientifically illiterate that a significant number think the clock is actually measuring something? I hope my readers don’t need me to tell them that no, the clock doesn’t literally measure the seconds to the Apocalypse; there is no reliable way to predict the odds of a nuclear war; there is no way even to approximate a prediction—not even in retrospect; in fact, when JFK said that the probability of the Cuban Missile Crisis escalating to a nuclear conflict was between 33 and 50 percent, that was just a figure of speech—what he meant was, “Folks, we were pissing ourselves.”)

“Yet there’s a deeper problem,” Larry continues:

Not only is the Doomsday Clock unscientific; the factors of its setting are now dominated more by policy questions than scientific ones. The former may be important, but claiming the authority of “atomic scientists” is appropriate only for the latter.

He then goes on (I paraphrase) to note that the group that announced the reset is heavy on dreary Irish vegan feminist fruit-juice drinkers.

Basically, he concludes, they’re only confusing things. They’re making policy recommendations, not scientific ones; they’ve lost touch with the clock’s original mission, so just stop already.

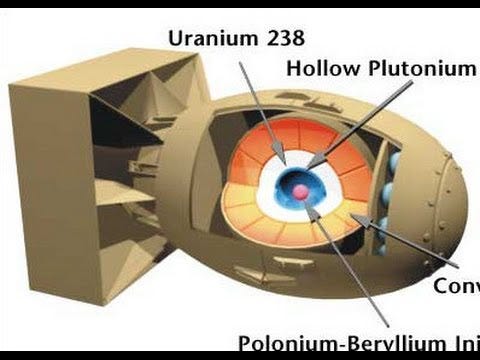

I’m sort of with you, Larry, but two points. First, the boundary between a policy recommendation and a scientific recommendation is too unclear to support the distinction you’re making. Rabinowitch, Einstein, and Oppenheimer were very qualified to explain just what would happen if one of those bad boys went off over Chicago. That didn’t mean they had the slightest qualification to say what should be done to minimize the chance that would occur. That is a policy question—or a matter of statecraft—pure and simple. The only science part of it is explaining why Chicago would be vaporized. At this point, we don’t need prestigious physicists like Rabinowitch, Einstein, and Oppenheimer to explain it to us. We can just Google it:

So this has always been about policy, not science. Frankly, after we dropped the Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I don’t think many people needed Einstein to persuade them that it was theoretically possible to build weapons that could destroy the world. So in truth, that clock has been about policy, right from the start, and you guys—theoretical physicists, I mean—have never been qualified to set it. We—the highly-credentialed International Relations specialists—actually have a better claim.

But no one cares what we have to say, because we can’t make reliable predictions to save our lives. We squander grant money by the billions trying to make our adorable little models work, but no matter how many purely ornamental differential equations we put in our papers, we’ve failed to improve upon the conclusions of the British statistician Lewis Fry Richardson, who studied the inception of war from 1820 to 1950 and concluded that no conflict’s size can be predicted beforehand—indeed, it is impossible to give an upper limit to the series—nor can their outbreak be predicted, for the series follows a Poisson distribution.

This, Larry, is why we appropriate the prestige of theoretical physicists such as yourself—men who have managed to make a few reliable, useful, predictions about the physical world—to bang on about what we strongly suspect but can’t prove. And because you guys are so vain (for good reason, I guess—your models work), you never suspect you’re being used. So that’s what was going on all that time you were on that board. Someone had the feelz about policy, so they trotted you out because they know the title, “World Famous Theoretical Physicist” is more likely to get people to pay attention than “Basically Unknown Person who Studies International Relations.”

That said, I’m glad you dropped in, because we seem to agree about this—we’re about to blow ourselves up, this is really bad—and maybe my readers will take this warning more seriously if they know it comes from a world-famous theoretical physicist.

Compared to climate science, which is very, very hard, the science part of the question, “What would happen in an all-our nuclear war” is fairly easy. We—for some value of “we”—can say with certainty not only how to build a nuclear weapon, but how to build a monster of a nuclear weapon, or several thousand of them. We can also say with certainty how you’d get them all to detonate over major cities around the globe, and how mightily awful the world would look afterward.

There are still some uncertainties—the nuclear winter hypothesis remains to be confirmed, as I ardently hope it will forever remain to be confirmed. (Note: the biggest uncertainty is a climate problem, because figuring out how the climate will behave in response to certain kinds of shocks is very hard, whereas figuring out what the world would look like generally, in the wake of a massive thermonuclear exchange, is not.)

Larry sent me this e-mail yesterday:

For over a decade I helped annually unveil the Doomsday Clock, which I felt was useful because once a year the clock reset would cause newspapers and television stations around the world to spend a paragraph, or 15 seconds respectively, on the existential danger associated with the vast worldwide arsenal of nuclear weapons. In association with that event I would often write something. An op-ed for a national paper or a short piece for a magazine. The reaction was almost always the same … no reaction at all. Because it has now been almost 75 years since the last nuclear weapon was used against a civilian population, the world has collectively buried its head in the sand and assumed that whatever it is that has caused none to be used since must be effectively ensuring that they will not be used again. The reality is far more scary. Over 10,000 weapons exist in the hands of the world’s superpowers, many of them on hair trigger alert. Countries like Pakistan and India are constantly on the verge of war and both have nuclear weapons. History is replete with accidents that have come within a hair’s breadth of resulting in nuclear weapons explosions. Yet even though they have zero strategic purpose, we keep maintaining them and building new arsenals. As Einstein said after the first nuclear weapon’s explosion: Everything has changed, save the way we think.

Wait. Wait. You didn’t need a theoretical physicist for that, did you?

Okay, time for me—the real expert—to take over.

First, they have a strategic purpose.

In 2008, a poll of experts at the Global Catastrophic Risk Conference, in Oxford, gave one percent odds on complete human extinction by nuclear weapons within the century, and 10 percent on the odds that a billion would be dead. The odds that a million would be dead, they figured, at 30 percent. (The attendees were of a gloomy kidney well before it was the height of fashion to be inconsolate at the prospect of our imminent doom.)

I don’t know what kind of experts these were—experts in global catastrophic risk, I guess—but real expertise could suggest only one answer: “We can’t measure this probabilistically. We don’t yet know how.”

The poll’s results were not science. They were guessing. Expressing a gut feeling. The real odds may be much higher or much lower. We have no way to calculate them more accurately. Why? because human beings are involved, and human beings are super-hard to predict. We just don’t know enough yet about human behavior to know what makes them likely to drop the Big One.

We do know this: Pushed to the wall, they’ll do it. The United States did it, twice. They won’t even feed bad about it, if it brings a war like the one we faced in the Pacific to an end. (We won’t even feel bad about when we begin to suspect it wasn’t the Bomb that caused Japan to surrender.)

Given that we can’t predict the outbreak of war, why do we keep trying to assign odds to the outbreak of nuclear war? And why do I say, “The risk is rising, and we should be a lot more concerned about this than we seem to be?” Is there anything rational we can say about the risk of nuclear war, and whether it is high or low, rising or falling?

Yes. The risk is a function of a number of variables, some measurable, some not. When the measurable variables rise, it’s time to worry.

The first is whether the weapons exist. If they don’t exist, they can’t be used. The number of nuclear weapons matters.

The second is the degree of hostility among the states or non-state entities that possess the weapons. If they’re at peace, they’re less likely to nuke each other deliberately. “Hostility” is hard to measure, but not impossible. Are these countries aiming their nuclear weapons at each others’ population centers? Hostile. Which country’s maps do they use when they conduct wargames? Is it labeled, “The Enemy?” There’s your clue. The number of nuclear-weapons states that are antagonistic matters.

The third is the risk of accident. If the systems that safeguard against accidents are sound, we’re less likely to nuke each other by mistake. “Competence,” again, is hard to measure, but not impossible. The country that just got confused in all the excitement and shot a civilian airliner out of the sky? God help us if they get nukes. The competence of the militaries of the nuclear-weapons states, and the systems they have put in place for communicating with their adversaries, matter.

It may be fraudulent—or at least, unscientific—to assign a numerical probability to the odds of a nuclear exchange based on these criteria, because it leaves out so many intangibles. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t relevant. I can’t tell you how likely you are to beat your wife tonight, but I can tell you for sure that you’re more likely to do it if you have a bad temper, a drinking problem, an unfaithful wife—and two hands. No hands, no wife beating.

If I know that you’re a habitual wife-beater who just lost his job, went to the bar, knocked back a fifth of vodka, and are about to walk home to find your wife underneath your best friend, I can confidently say, “The odds that you’ll beat your wife have just risen sharply.”

No, I cannot predict that you will beat your wife scientifically. A human being is involved. You may take a look, think how unpleasant things would be in prison, and say, “She’s not worth it.” You may remember what your therapist said about using your words and counting to ten. God might intervene and save your soul. There is no way to be sure what a human being will do.

Nonetheless, when I say, “The odds that you’ll beat your wife have just risen sharply,” it is not an empty statement, nor is it a prediction on the order of, “I just know this fair coin will come up heads, because tonight’s my lucky night.” It’s an unscientific but reasoned judgment.

The Board of The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists is right, in my view, to emphasize the ups and downs of the international power struggle—whatever Eugene Rabinowitch might have thought. The clock moved forward in 1953 with the development of the hydrogen bomb, to be sure, but no one would have been so worried—nor should they have been so worried—had the United States and the Soviet Union not been locked in an existential war that only one would survive.

Let’s look at the history of the clock:

When it ticked closer to midnight in 1974, it can’t have been because of the development of missiles with multiple warheads. We tested the Minuteman III in 1968 and deployed it in 1970. The Soviets launched the R-36 in 1963. It entered service in 1968, and was, theoretically, MIRV-capable from the outset. After we introduced the Minuteman III, they MIRV-ed up the R-36, but in 1975. The horror of these developments did not lie in the new technical ability, but in the change of strategic doctrine necessitated by the development: MIRV’s make attacking less expensive than defending. Land-based MIRVs are particularly destabilizing because they’re vulnerable to attack and create an incentive for an adversary to strike first.

So what happened in 1974 to move the clock forward? I would guess it the testing of the Smiling Buddha—and the end of détente. In 1974, the SALT II talks ground to a halt. I don’t know for sure if that’s why the clock was moved closer to midnight, but I bet that had something to do with it.

Generally, the clock moves away from midnight with the signing of arms-control treaties. It moves closer when these treaties fail, and sharply closer when new nuclear powers come into being. France and China tested their first weapons in 1968; the clock ticked closer to midnight. India tested in 1974. Pakistan tested in 1998: closer to midnight. North Korea, 2006: closer to midnight. By contrast, the board liked the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, SALT I, the ABM Treaty, and the end of the Cold War. The clock moved further from midnight after all of these events.

If I’m right about why the clock moved, those were reasonable, if imperfect, grounds for moving it. They’ve since confused matters greatly by trying to measure and include the threat of climate change—a completely separate problem—and I agree that they should not have done this. I even agree, perhaps, that it’s time to get rid of the clock. No one but me pays any attention to it, anyway.

But they aren’t wrong to point out that new technologies are increasing the risk of nuclear war. Assessing the risk necessarily involves considering the impact these technologies. How much do they increase it? It can’t be quantified, but yes, the destabilization of what they call the “information ecosphere” increases the risk, as do new developments in artificial intelligence, space, and hypersonics.

They’re right that deepfake technology raises the likelihood of misunderstandings that could lead to war. They’re right that AI is now being used in military command and control systems, making them vulnerable to hacking and manipulation. They’re very right that the deployment of hypersonic weapons—which limit response times— is destabilizing. They’re right to say this:

The overall global trend is toward complex, high-tech, highly automated, high-speed warfare. The computerized and increasingly AI-assisted nature of militaries, the sophistication of their weapons, and the new, more aggressive military doctrines asserted by the most heavily armed countries could result in global catastrophe.

They are right to point out that relations among the major powers are growingly hostile, that the global balance of power is shifting, that our efforts to roll back North Korea’s nuclear program have failed, that our policy toward Iran hasn’t succeeded, and that the world is growingly chaotic.

They are also right to say that no one is saying or doing what you’d hope they would say and do under these circumstances. The world around, publics are devoting their anxious energies to worrying about the Wuhan coronavirus, which is frankly nuts. Yesterday, at the pharmacy, I saw some neurotic woman buying her son a box of face masks. (That memory’s going to make for one hell of a psychotherapy session some day.) I considered telling her that all she needed to do was wash her hands, and for God’s sake, stop biting the heads off those live bats. But there was a long line behind us, and it wouldn’t have been fair to everyone waiting on it.

I’ll say more about what worries me, and what we can do about it, tomorrow. But first, did you know that there is such a thing as an effective cellulite cream? You’ve all been told that there isn’t—that it’s a scam. But that, not the miracle cellulite cream, is the lie.

Tune in tomorrow, and I’ll tell you all about it.

"Rabinowitch, Einstein, and Oppenheimer were very qualified to explain just what would happen if one of those bad boys went off over Chicago."

Having grown up on the streets of Kankakee, my brother and I mugged in Chicago, and the place wholly unimproved since then, I'm not convinced that would be a bad thing.

"We squander grant money by the billions trying to make our adorable little models work, but no matter how many purely ornamental differential equations we put in our papers, we’ve failed...."

Well, that's because of two fatal errors you guys make that my august lay personage has avoided. One is that you're using those cute differentials instead of Heisenberg's Uncertainty equations.

The other is that your perspective is wrong: you insist on looking at the thing from the outside. We're not outside anything; we're all of us inside Shroedinger's box, and no one has opened it, yet. You're in good company, though, even Pandora screwed that up. So are the aliens that, every several 10s of millions of years, throw rocks at us. Everybody better hope we don't escape from the box and get out among the stars. We're gonna come knocking, and we're gonna be pissed. And with two satellites already reaching interstellar space, we've already turned our backs on the bull and are contemptuously dragging our capes on the ground daring it.

A nit: "It may be fraudulent—or at least, unscientific—to assign a numerical probability to the odds of a nuclear exchange based on these criteria, because it leaves out so many intangibles."

Not at all. It would be fraudulent--or at least, incompetent--to assign a numerical probability without also providing the probability(s)' error bar(s) and an explanation of the bars' origins and development. It's entirely reasonable to make probability assessments so long as those assessments have their contexts.

"...worrying about the Wuhan coronavirus, which is frankly nuts."

There are these, though: https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/health/health-problems/mystery-lab-next-to-coronavirus-epicentre/news-story/3e5a32fe77263fe8ca81b091cc8d9c42

and https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.01.30.927871v1.full.pdf

I haven't had a chance to evaluate the quality of those sources, but I don't think it's nuts to worry about the coronavirus given the PRC's track record and their active rejection of our offer to send CDC and other disease experts to help them.

The masks are useful, too, not just for coronaviruses but for any disease capable of riding water droplets. They confine a wearer's sneezes and coughs to that wearer, and they shield others from the coughs and sneezes of non-wearers.

As to biting the heads off bats, we had a cat in Las Cruces who would eat the heads of baby rabbits and leave the rest of the corpses lying around the house. That place has got to be haunted by the ghosts of headless baby Chucky bunnies.

Eric Hines