Discipline and Pandemics

Meditations on Captain Crozier, military readiness, and our geopolitical nightmare

Personal Anecdote of the Day

Warning: There’s no news in this newsletter. If you want news, skip this and wait for the next one.

You may be wondering why, after my stirring announcement that from now on, I’ll be imposing discipline on this newsletter—Order! Sections! A schedule! A word limit!—you haven’t heard a word from me.

Indeed, a thoughtful reader sent me a concerned message: You didn’t catch it, did you?

Not to worry, readers. I’m A-OK. Fit as a fiddle. So’s my Pop.

But here’s the truth. I found it so difficult to organize my thoughts in the fashion my brother suggested that after trying all day long to do it, I gave up in frustration—and I did that for four days running, and thus sent out no newsletter at all.

It’s not that I have nothing to say, believe me. I’m sitting here now with 36,322 words in my draft file, at least half of which are interesting—nine heartfelt denunciations, sixteen letters from my readers, four charts—but I just can’t organize them into a 1,200-word newsletter under five distinct subheadings, no matter how hard I try.

I hate myself for this.

But I can’t afford the indulgence of wallowing in self-hatred and publishing nothing. That’s a worse outcome by far than writing long and undisciplined newsletters.

So screw it. I’m going back to being myself. My brother’s ideas are terrific, and I’m sure he’s right, but I just can’t do it. I will keep it shorter, though.

I’ll just sent out more newsletters.

First Question of the Day

Before I launch thirty 1,200-word newsletters your way (because those 36,322 words are not going to go to waste) let me run something past you.

I started this newsletter, basically, on a lark. I didn’t think of it as a business. I figured I’d use it to burn off stray random thoughts here and there, then I figured I’d show off my book (which now has to be completely rewritten in light of the pandemic, but if I think about that I’ll go nuts, so I won’t).

I wasn’t expecting a global pandemic to trap me in my apartment and turn this newsletter into my entire life.

But so it has, and here I am. Naturally, then, I’ve been asking myself, “How can I make more money from this newsletter?” Apart from “make it shorter,” which I promise to do, here’s what I’ve concluded. Tell me if you think I’m wrong.

Chart of the Day

This is a typical day. Every day, “Direct” is the top category, followed by Twitter and Facebook.

What does “Direct” mean?

Well, I don’t rightly know. I don’t how Substack’s collecting this data, or whether they’re using a consistent definition, or even whether they’re telling the truth. Those numbers could mean many things; depending what they mean, the policy implications may be radically different.

But like all policy makers, I have to make the best decisions I can based on the limited information I have.

Here’s my hypothesis: “Direct” means you forwarded my newsletter to a friend, who then opened it directly—qua newsletter. “Facebook” and “Twitter” means you shared it on social media, and your friends opened it on the Internet, as if it were a blog post.

As you can see, “direct” results in many more free sign-ups.

So would you please share this newsletter with your friends? As often as possible? (Perhaps not this one, in particular, because it’s a meta-newsletter, not a news- newsletter.) But specifically, when you like a newsletter and feel like sharing it, would you please do it via email?

Also, try sending it to people you don’t know, and to people who you don’t think will like it. I didn’t mean to try that, but I found out that it works better than you’d expect. It was a natural experiment. I didn’t realize the buttons I was pushing would result in Substack gobbling up all of my Gmail contacts, including everyone who had ever sent me an email in my entire life. But, well, that’s what those buttons did. So initially, this newsletter was delivered to the entire board of the Federal Government of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and all of my ex-boyfriends. (There was no overlap.)

I wouldn’t have thought spammers were my target demographic, but it turns out that the people who send us the spam are real. Or one of them is, anyway. I was amazed when I got a lovely email one day from the customer service representative of a your-discretion-is-guaranteed site that sells products such as this. He asked to be taken off the mailing list because it was against company policy to read mail like this at the office. But he gave me his own email address. And he subscribed.

So go ahead—forward it to your entire contact list. (Yes, you’re legally allowed to do under the GDPR, if you’re wondering. You’re just not allowed to send that contact list to me.)

How often should I forward it?

Experts say you can’t do it too often.

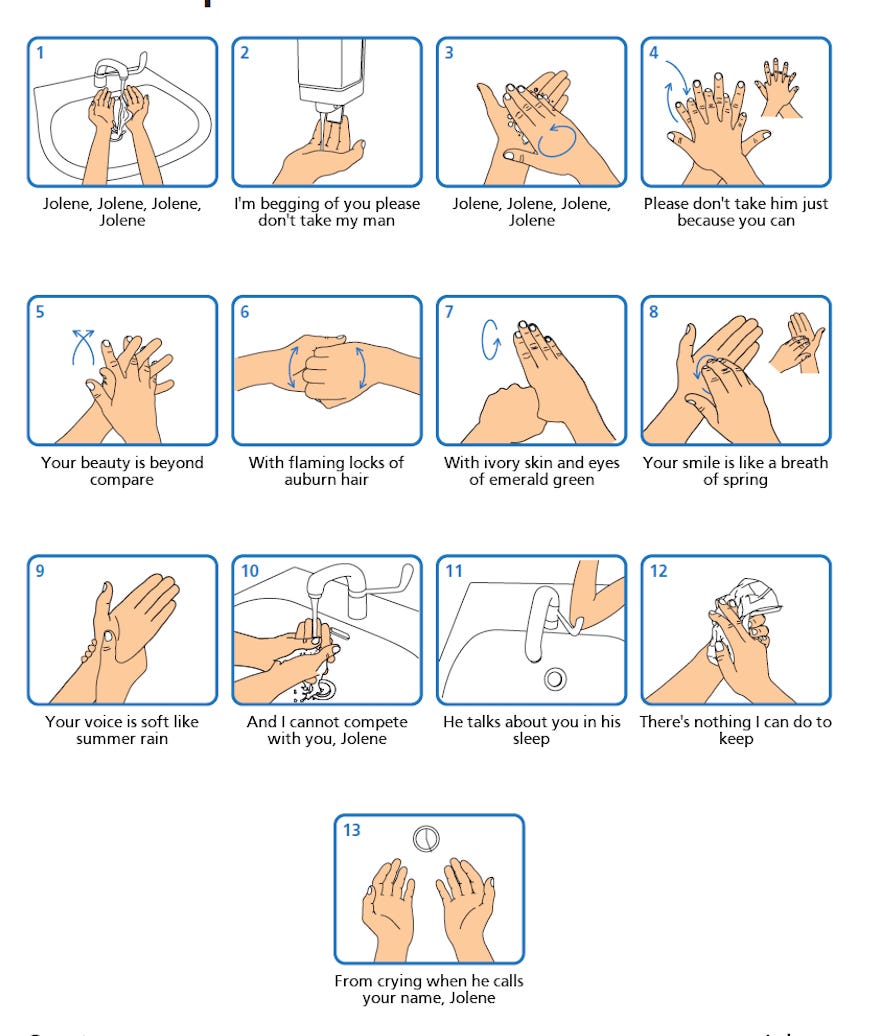

One way to know whether you’ve been forwarding the newsletter often enough is to make “forwarding Claire’s newsletter” part of your hand-washing routine, like so:

Step 14: Joleeeeeeeeen!

I hope that was helpful.

Speculation of the Day

Why is “direct” so much more effective than sharing it on social media?

Here’s my hypothesis. When your friends receive the newsletter via email, they see that it’s a newsletter, not a blog. They quickly realize that they too could receive this fine product—directly!—right in their own In Boxes. All they have to do is push the button.

Denunciation of the Day

Today, I denounce Substack’s buttons.

Substack only gives me a handful of button options. And the ones they give me are confusing to readers—I know this, because confused readers write often to tell me so. None of them say, “Sign up for free,” even though Substack does, obviously, understand the difference between “Free signups” and “Subscribers,” given that they disaggregate then in the data they send me. I fear these damnable buttons are working against me. People hesitate to push them, because they’re not sure what they do.

Let me show you what I mean. If you push the button below—check for yourself— you’re offered a choice: “Free signup” or “Subscribe.”

But how would a reader know there’s a “free” option? I bet they’re more hesitant to push it than they should be, because they think I’m about to hit them up for money.

I could use the “custom” button to create a new one, and perhaps I should. What do you think, would this be less confusing?

Double Denunciation

Let’s review the other buttons, while we’re at it.

If you push this button, you share this particular newsletter:

If you push this one, you share the whole newsletter, in toto:

But how are readers supposed to understand that unless I tell them? And I can’t tell them in every single newsletter, can I?

I can use the “custom” button to create a link to anything I want, but there’s a strict character limit. It can’t be longer than the button below. What do you think:

Important Question of the Day

You may have looked at the chart of the day and asked yourself, “If Claire’s trying to make money, why would Claire think “free signups” is the critical statistic to track? Isn’t “subscribed” the goal?

Excellent question. Here’s my thinking on this:

Visitors = Susceptible

Free signup = Infected

Subscribed = Dead

So let’s model it this way. Let St , It , and Rt (“R” for “Rest in Peace”) be the number of visitors, free signups, and subscriptions, respectively, at time t.

Assume

St + It + Rt ≡ N (i.e., the population is closed);

Readers are exposed to my newsletter at the rate of α1 per unit of time;

Upon reading my newsletter, a susceptible reader will sign up for free with probability α2, whereupon he becomes capable of forwarding it to every single one of his friends, acquaintances, and co-workers.

This defines a continuous time Markov Chain with the state (St , It). Conditional on St = S and It = I

Pt(St+h = S − 1, It+h = I + 1) = αSIh + o(h)

Pt(St+h = S, It+h = I − 1) = ρIh + o(h),

where α = α1 × α2, and

Et(St+h − St) = −αSIh + o(h)

Et(It+h − It) = αSIh − ρIh + o(h).

If we now formally take h → 0 we arrive at this dynamical system:

… a classic Kermack-McKendrick model.

Yes, yes … I can already hear your objections. You think I’m over-simplifying this, and besides, we have no idea if this data’s any good.

You’re right. But that’s the point: It’s a model. As Zeynep Tüfekçi explains, right answers are not what a model is for.

My hypothesis is that schematically, readers go through consecutive states: S → I → R. The more free signups I get, the more likely it is I’ll have paying subscribers, and I’ll bet you anything that’s roughly right.

The really important question of the day

But perhaps you aren’t that interested in the model. Perhaps you just want to know how likely is it that you, personally, will sign up to receive this newsletter for free, and yet somehow wind up paying for it.

Let me reassure you. Unless you’re in a high-risk cohort, the odds that you will pay for this newsletter remain low. There is no cause for panic.

The data are hard to parse—and inherently unreliable, given that no one can trust any number that comes out of Facebook—but what we know so far suggests that unless you’re in that high-risk cohort, the odds you’ll become a paying subscriber are not significantly greater than the odds you’ll die of the coronavirus.

Let’s speculate, though, that I’m severely undercounting the number of people who read my newsletter without paying for it. That’s possible. I have no way of knowing, for sure, because I don’t really understand how Substack works and haven’t yet figured out a reliable way to look at the real numbers.

If we assume I’m severely undercounting, your odds may be much lower—perhaps as low as 1.1 percent, even lower than the odds you’ll pay to subscribe to Matt Taibbi’s newsletter, and you take that risk every day without thinking twice about it, right?

You wouldn’t shut down the entire global economy to eradicate that risk, would you?

Why we have to shut down the global economy

If you just said, “Of course not,” I’m afraid math—or metaphor—isn’t your strong suit.

Even though very few people go on to subscribe, it’s still a numbers game. If enough people sign up to read it for free, the 1.1 percent who wind up paying will be huge—it will be more than enough to keep me from destitution. If I succeed in persuading you to send this to 2.25 of your friends, and if you persuade them to send it to 2.25 of their friends—and if this trend continues—I will not wind up destitute on the streets. In fact, since no one’s immune to my charm, I’ll be a millionaire before there’s a vaccine.

(I’m serious, by the way, both about the business model and the metaphor. Please do forward this by email—but more importantly, please, please, stay home.)

Welcome!

Are you a new reader who just arrived as a result of my appeal? Hi! So glad to have you here! Make yourself at home: mi casa es su casa.

It’s about to get interesting. Stay tuned: In the next letter, I’ll share my meditations on Captain Crozier, what we should learn from our failure to prepare from this pandemic, and why I should—or shouldn’t—resign from punditry altogether because I didn’t see it coming.

Just as soon as I pare it down to 1,200 words.

"the entire board of the Federal Government of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and all of my ex-boyfriends. (There was no overlap.) "

Why is there (see what I did there--present tense) no overlap? There must have been on that board at least one Army Lieutenant who was stinking rich and needing a bride, or a paramour, to help him move his riches.

And: I've always hated that song and its contemptible singer (the fictional one; there's nothing contemptible about Dolly Parton), with her rank cowardice. "Her" man deserves better, whether or not Jolene is that.

"And I can’t tell them in every single newsletter, can I? "

Sure you can. A boilerplate footer at the end of each newsletter--which, like TV discount codes for an advertised product (they do those in France, don't they? I got a bellyful of all the "Neu, von K-tel" ads in Germany...), will tell you the reader read the whole thing.

Separately, you really need to model using logistic equations as applied to crop responses--because you're trying to grow readers and harvest the subscribed ones. (Sadly, Substack's comment facility won't let me present integration formulations or partial differentials.)

Eric Hines