Abu Ivanka al-Amreeki and the Bureau des Étrangers

If you have a few minutes, read this essay by Peter Harling, The Syrian Trauma. He wrote it in September 2016, but I only discovered it about two weeks ago. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it, though.

“Every now and then,” he wrote,

the conflict in Syria produces an iconic image of horror and suffering, which many brandish as an undisputable truth that will finally shake the world into “doing something.” Others break down at the sight of such images, or instinctively avert their senses. Mass killings and disappearances, industrial-scale torture and sexual abuse, gruesome staged executions, starvation tactics, the continued use of chemical weapons, napalm, cluster and barrel bombs, not to forget the torments of desperate emigration – all have spawned morbid emblems of their own.

“Arguably, all conflicts are traumatic,” he continues,

… Syria seems nonetheless to bring in something different, hard to pin down — an elusive truth that is precisely what we should not fail to understand. Indeed there are many layers to the Syrian trauma. First, Syrian culture, in normal times, is remarkably civil. The Syrian dialect of Arabic is ravishingly polite. Education is a source of national pride. Unlike many other parts of the Arab world, urbane mores permeated the countryside more than a rural ethos reshaped the city. Communal coexistence, edgy on occasions, was nevertheless a profession of faith.”

It occurred to me, as I kept reading, that the Syrian civil war is an event, like the Holocaust, that showed us something new about our innate capacity for depravity. If the Holocaust made clear that humans had the ability to unite the task of murder with the age of industrial efficiency, Syria showed us that we could unite murder on a mass scale with instant, global communication — and remain indifferent, bored, even angry with the victims of what has surely been the most widely-viewed crime of its sort in human history.

Atrocity after atrocity has been documented, filmed, frantically uploaded, broadcast, in real time, to an indifferent world. It is hardly the world’s first terrible war, of course. But it’s the first conflict of this magnitude to take place in the age of the Internet and the cell phone. It’s the first time the whole world has been able to see, in so much detail, the faces of the grieving and the dead, to hear the voices of victims begging for help. Anyone with a phone can even call Syrians themselves to speak to them directly — on Skype, no less, for free. And the world, having seen this, replied, “So what.” The world listened as half a million Kitty Genoveses screamed for help. It shrugged.

Thus, wrote Harling,

… a fifth and related source of trauma for Syrians … the horrifying spectacle of an outside world watching on as their country is pointlessly and endlessly tortured. They have learned the hard way how shallow and callous our media and politics can be. People who remember every sorrow in every detail must contend at best with generalized amnesia, at worst with conventional wisdom dismissing their life experience. Their misery is met with fatigue; their flight to safety with hysteria.

On Tuesday, videos and photographs displaying the aftermath of a chemical weapons attack on Khan Sheikhoun, south of Idlib, emerged. Again, anyone with a cellphone could see what it’s like to experience this:

I expected the world to meet this with the same indifference as it had all the previous attacks. And for all the reasons that don’t bear repeating, I certainly didn’t expect President Trump to do anything about it. But yesterday the news broke in the middle of the night (in Paris, anyway) that the United States had launched 59 Tomahawk missiles at Shayrat Airfield, targeting “aircraft, hardened aircraft shelters, petroleum and logistical storage, ammunition supply bunkers, air defense systems, and radars.” That’s the airfield from which the planes that dropped chemical weapons on Syrian civilians — and then bombed the hospitals treating the victims — took off.Usually, when news of this magnitude breaks I sit glued before my screen, trying to figure out what’s going on. But I couldn’t this time: I saw the headline, then had to rush out the door. I’d been awake for hours already, assembling my documents and preparing to spend a long and stressful day at 17-19 rue Truffaut.

17-19 rue Truffaut

Like all foreigners who live in France, I need permission to be here. My case falls under an unusual bureaucratic category called “exceptional family circumstances.” But as you can imagine, the Bureau des Étrangers at 17-19 rue Truffaut is overwhelmed by petitions from desperate people with good reasons to want to be in France, ranging from “exceptional family circumstances” to “I will be killed immediately if I go back” to “That’s not a good enough reason, you have 48 hours to leave the country.”

Given the number of applicants at the Bureau des Étrangers on any given day, and given the general principles under which the French bureaucracy labors, these visits are stressful.

I go with everything I can imagine a French bureaucrat wanting to see: my birth certificate, my grade school report cards, my college transcripts and diplomas, my medical records, my father’s medical records, my mother’s last will and testament, my certificate of health insurance, tax records, rental contract, phone bills, electricity bills, my grandfather’s service medals, every book and every article I’ve ever written, half a dozen passport-sized photographs, notarized translations, duplicate copies, triplicate copies — I go with so much bureaucracy-pleasing paperwork that I have to put it in a suitcase. I arrive at dawn, demurely dressed, and wait on line in the cold with all the other stressed, demurely-dressed people until they open (promptly at 9:00 a.m.) – and then we wait on line for hours more.

As we wait together, we naturally bond over our anxiety about what awaits us inside that forbidding building. We’re all desperately eager to appease and please the bureaucracy, but none of us really understand what it wants — no one actually knows, in fact, including the people who work there. We all fear angering it by accident. We’ve all heard stories about things that can happen — to a cousin, an uncle, to someone who worked as a dishwasher in a restaurant in the 9th — and none of us know what to make of these stories or whether it could happen to us.

The first time I went there, it suddenly occurred to me to wonder if this could be the very place my grandparents stood on line, in 1941. I had heard the story of “standing in line” from them, but I don’t think they ever said where, exactly. My grandfather had been promised French citizenship for his service in the Foreign Legion. He’d fought in the Battle of France, on the Belgian border. He was one of only 250 survivors of his 1,250-man regiment. But then France fell, and the only thing they could hope for was an exit visa. I wondered if they’d stood on that line, just like me. But with one very big difference, of course. If the bureaucrats looked at my papers and said, “No,” I’d be deported. Had the bureaucrats inside looked at my grandparents papers and said “No,” they would have been sent to the death camps.

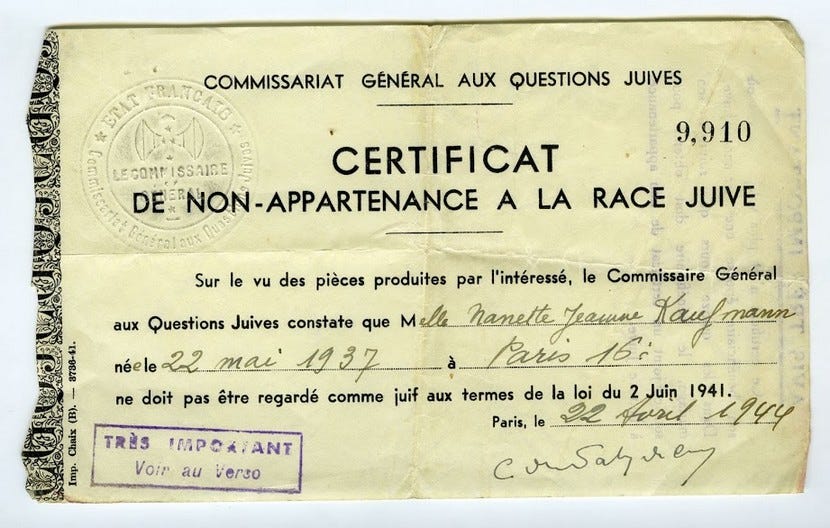

An official certificate of “Non-belonging to the Jewish race.”

I don’t know whether my grandparents fully understood, at that time, what would happen to them if they were sent to the camps. I asked my father whether they knew, but he doesn’t know, either. There were certainly many rumors about by 1941. But people refused to believe what they were hearing. Perhaps my grandparents didn’t allow themselves to think of that while they were waiting. You can’t think like that if you’re trying to persuade an overworked bureaucrat that all of your paperwork is in the right order and makes perfect sense.

Yesterday morning, everyone’s eyes, like mine, were glued to their cellphones. We were all trying to figure out what had just happened in Syria and what it meant. We were all a bit scared to talk about it with each other. None of us knew for sure where the other people around us came from, after all. Obviously, I didn’t want to end up in a shoving match with a Russian — in front of the cops and multiple surveillance cameras — right before trying to make my case to the officials that I’m a harmless, law-abiding, middle-aged woman who wouldn’t even inconvenience the French state, no less get in a public brawl right in front of the Préfecture de Police. It was strange: everyone was reading the news on their screens, furtively glancing at each other, and then tentatively, whispering, “Qu’en pensez-vous?”

What do you think?

It was definitely not the right time or place for me to say — as I usually would — “Hi! I’m an American journalist, and I’d like to know where you’re from and your reaction to President Trump’s decision to launch cruise missiles at a Syrian air base.” It wasn’t even the right time for me to guess where people were from. Wherever you’re from, when you’re on that line, you speak French and you act as assimilated as you know how to act. So I can only say what I saw and heard; I have to guess what it meant.

There was a Frenchman near the line, or at least his accent was Parisian. I think he worked inside and had come out to smoke. He was about forty. He glanced at the screen of my phone, which — like his, like everyone’s — showed the words, “Frappes en Syrie : la Russie dénonce « une agression », les alliés de Washington applaudissent.” We made a bit of small talk. “Vous êtes américaine?” he said. (My accent gave it away.) I said yes. He’d been to New York once, he’d heard California was beautiful. Did I like France? We both looked at my phone. I said, “Qu’en pensez-vous?”

He looked as if he wasn’t sure. Then he said, Avez-vous déjà été en Normandie?”

I said that I had.

“C’est impressionnant, Je pense à ces gosses américains. Ils ont traversé un océan, sont venus dans un pays dont ils n’ont jamais entendu parler, pour faire cela pour nous … “

Believe me, this is not usually the first thing people here say when I say that I’m American. I can’t say for sure why he said it or what he was thinking.

There were a handful of men next to us from Mali, I’d guess, or from somewhere in Francophone Africa. They were perhaps in their thirties. Qu’en pensez-vous? I said to them

One said, tentatively, “Je pense que … j’espère que cela peut être bon, si ça fait bouger des choses … Si cela peux changer quelque chose … “

Another interrupted, “Non! Je ne suis pas d’accord! Ils ne sont même pas allés à l’ONU. Chaque fois que l’Amérique s’implique, elle empire!” He realized he’d raised his voice more than he intended, and returned to a hushed tone. “Mais c’est trop tard, ils auraient dû le faire depuis longtemps, les Américains. Les Syriens, ils ont trop souffert.”

“Assad, il est un fils meurtrier [redacted],” said the first. A statement, not an argument. Everyone near us nodded quietly. No exceptions on that.

A woman from, I’d guess, somewhere in north Africa, there with her two kids, both runny-nosed, asked me, “Pourquoi Donald Trump a-t-il changé son avis? Il n’y a que 48 heures, il était quelqu’un totalement différent.”

Usually, I can handle any and all questions about American politics and how America works. But I was as stumped as my interlocutor. I told her I honestly hadn’t the first clue. That I was completely surprised. That it was the last thing I thought he’d do. “Mais je suis très heureuse que nous l’avons fait. Enfin."

Everyone fell quiet.

We were all still waiting on line when the jokes about Abu Ivanka al-Amreeki hit the Internet. They made the Malians laugh, although no one — literally no one but me — got the joke about Kushner of Arabia.

I hope everything went okay for everyone else on that line. I hope none of them were deported.